The graying of Michigan farmers, and what they will leave behind

MASON – Jeff Oesterle may be the new face of farming, even though that face is 65 years old.

At an age when his non-farmer neighbors in Ingham County, are retiring and collecting Social Security checks, Oesterle is planting and harvesting 4,500 acres of corn, wheat, soybeans and hay.

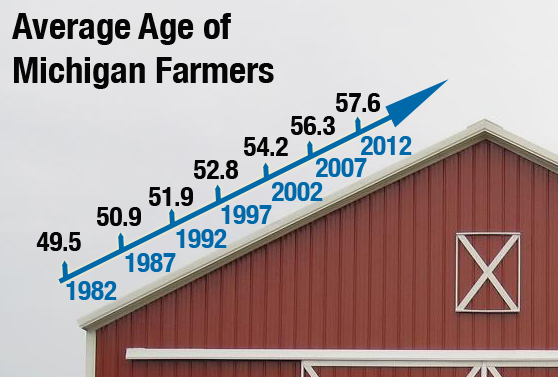

The average Michigan farmer in 2012 was 57.6 years old, eight years older than the average for farmers a generation ago in 1982, and almost 16 years older than the median Michigan worker in 2012, the most recent statistical year available. While the graying of Michigan’s farmers isn’t likely to have an impact on consumers, it is reshaping what we think of as traditional family farms in the state.

“People like to look at a little 80-acre farm that raises a few head of hogs and cattle and maybe a few chickens running around, Oesterle said. “It looks good in a magazine.” But it’s increasingly no longer the norm in Michigan.

In reality, family farms are larger than ever, pricing out many young people who might in past generations have purchased farmland, and setting the stage for major turnover in the next 20 years as older farmers retire, according to David Widmar, an agricultural economist with Agricultural Economic Insights, and a researcher at Purdue University.

The average age of farmers is over 50 in every county in the state, ranging from 50.8 in Oscoda County in northeast Michigan, to 61.9 in the Upper Peninsula’s Schoolcraft County.

The graying of the Michigan farmer sounds like a story of demographics, but at its root, it’s about economics.

“It takes such a large amount of capital to start a farm,” Oesterle said. “It’s almost impossible … for young people to get into the business.”

In the past, farmers passed their farms onto their children, but “more and more children are not staying in agriculture,” said Frank Wardynski, the Michigan State University beef and dairy extension educator in Ontonagon County, where the average farmer was 61.4 in 2012. “So mom and dad are farming until they retire, and then selling the farm.”

And young people can’t afford to buy those farms like they might have a generation or two ago. “Usually they’re selling it to other older farmers. Maybe not as old as them, but not a new farmer,” Wardynski said. “No one graduates from high school with enough money to start doing that.”

The trend is the same across the country. The average age of farmers is rising across the United States, ranging from 55.7 in Nebraska to 61.1 in Arizona. More than a third of farmers were over the age of 65 in 2012, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. There were more farmers over the age of 65 than all farmers under the age of 45 combined.

To some extent, the graying of farmers across the U.S. and in Michigan is a reflection of the U.S. population as a whole growing older, said Widmar, the Purdue researcher, who studies ag economics and trends and has written about aging farmers.

“The U.S. workforce is aging, we’re living longer and we’re working longer in life,” Widmar said.

One hundred years ago, the largest percentage of farmers were between the ages of 35-44, Widmar said. By 1980, the largest share were aged 55-64. Now, the largest proportion of farmers are over 65.

“At some point, they’re going to exit production,” Widmar said. “When that happens, it’s going to change the dynamics of who controls farmland.”

Fewer farms, more corporate

That could mean more corporate-owned farms. But it almost definitely will mean a further concentration of farmland in fewer hands, as those with the capital to buy farmland extend their holdings, Widmar said.

One third of all farmland in the nation is owned by farmers over age 65. The USDA estimates that 10 percent of all farmland will change hands in the next five years.

INTERACTIVE MAP: How old are YOUR farmers?

“How will that play out? Is there a family member who is going to step up and continue the operation? We don’t know that from the data,” Widmar said. “What we do know is, when you look at the trends, when a third of the population leaves, there aren’t a lot of farmers to step up and fill that void.”

MSU Extension officer Steve Lovejoy says there’s no need to panic. He argues that the farmer-age data distributed by the USDA is misleading because it only considers the age of the “primary operator” of a farm, not everyone who works there.

“You’ve got grandpa who is still considered the patriarch of the family, and maybe two generations working with the farm who aren’t counted,” Lovejoy said. “That’s different from (median worker age) in other aspects of the economy.”

That’s the situation for Ingham County farmer Oesterle. “My grandfather was a farmer and my father was a farmer,” Oesterle said, “and now I have two sons who work on the farm and grandchildren who are interested in farming.”

Some older farmers who don’t have children interested in taking over operations are finding ways to pass along their acreage to young farmers. Lovejoy says some farmers have signed contracts with young workers who operate their farms in exchange for a stake in the land that grows over time.

The USDA, meanwhile, is developing what amounts to a matchmaking service, connecting veteran farmers looking to retire with young farmers willing to work their way to ownership.

The National Young Farmers Coalition has pushed for policy changes that would ease the path for young agriculture workers, such as student loan forgiveness programs similar to those that exist for some teachers and physicians.

“I see stories that say, ‘Oh my God, farmers are dying off,’” MSU Extension officer Lovejoy said. “Well, I have no doubt the land is going to get produced as long as my grandchildren live.”

“I don’t think we’re going to run out of farms,” Widmar said. “But I do think we’re going to see a transition from farmers to farms, where the business doesn’t cease to exist (when a farmer retires or dies). Producers are going to become larger and have a different skill set.

“I don’t think consumers will notice anything,” Widmar said. “But inside the industry, the players are going to change.”

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Jeff Oesterle, center, is one of a growing number of Michigan farmers who continue to work the fields after age 65. He has help on his farm from his sons, Don, on the left, and Russ, right. (Courtesy photo)

Jeff Oesterle, center, is one of a growing number of Michigan farmers who continue to work the fields after age 65. He has help on his farm from his sons, Don, on the left, and Russ, right. (Courtesy photo)