Michigan and the death of entrepreneurship

In a tiny brick building on the west side of Jackson, Jeff Drushal is living his dream, stepping out onto a ledge that is both frightening and exhilarating.

Married and with a daughter, Drushal, 34, just left a steady job as a supervisor in a machine shop and surrounded himself with decades-old – but still working – metal cutters, lathes and welding guns. He is betting on his own skills and business acumen to make the transition from employee to employer.

In five years, he hopes to generate enough work that he’ll be able to hire and train a dozen workers at his metal fabrication shop in this struggling manufacturing city of about 33,000.

To say he has doubters is an understatement.

“Half of them think I’m crazy,” he said of his peers. “And half the people think I’m going to answer only to myself – and sit at home and watch TV all day.” He chuckles. He won’t be watching much TV.

Michigan needs a lot more people like Jeff Drushals. Instead, Bridge found, the state has too many business owners who have either closed shop or are hesitant to set up new businesses.

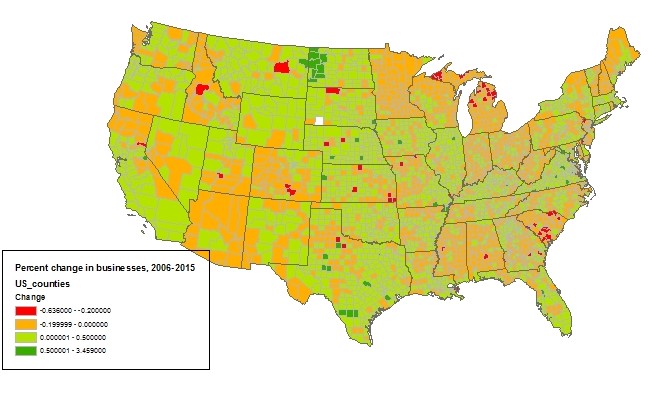

Counties across Michigan, mostly in the rural north, have suffered among the steepest declines in the nation. Indeed, over the past decade, nearly 1-in-4 counties in the U.S. with the sharpest drops in businesses were in Michigan.

Roscommon County, home to Houghton Lake, lost nearly 24 percent of its businesses in this period, while Genesee County, home to Flint, lost 16 percent, or more than 1,300 employers.

Statewide, Michigan has lost nearly 18,000 businesses. And experts say any hopes of reversing the state’s decline rests on a couple of fundamentals: more access to seed money, and improving the business literacy of first-time entrepreneurs.

A recent national study found that while business openings remain flat in much of the nation, real growth is taking place in just a handful of counties across the nation, mostly around major U.S. cities.

“You need new businesses to create new jobs,” said John Lettieri, co-founder of Economic Innovation Group, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, which did the analysis.

The report, “The New Map of Economic Growth and Recovery,” noted that number of new businesses opening nationally from 2010 to 2014 was less than half of those opened between 2002 and 2006. Much of the new business activity was limited to just 20 counties nationally, mostly around thriving metro areas like New York City, Los Angeles, Dallas and Miami.

None were in Michigan.

“Missing” generation looms

The impact of shuttered storefronts has been particularly harsh in Michigan.

Huge swaths of the state are seeing far fewer businesses selling food, offering services or making things, according to employer data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics analyzed by Bridge. In fact, all but two of Michigan’s 83 counties saw the number of employers decline between 2006 and 2015, during which the state lost nearly 18,000 businesses statewide.

Only 51 counties nationwide lost more than 20 percent of its employers between 2006 and 2015. Of those, 12 are in northern Michigan.

“(T)he geographically uneven nature of the collapse in start-ups implies that wide swathes of the country will soon be contending with the consequences of a missing generation of enterprise,” EIG reports.

The sobering statistics raise questions about Michigan’s long-term prospects for economic revival, despite the state enjoying low unemployment rates and rising numbers of jobs, often in existing businesses that are hiring following the recession.

EIG’s report did not address why some states did worse than others but it did note that rural counties – like those across northern Michigan – saw the biggest losses.

Lettieri said one of the biggest obstacles to people opening new businesses has been access to capital. Start-ups typically get their initial cash from their savings and homes. As Michigan workers well know, wages and housing values in the state remain below pre-recession levels.

In addition, Michigan, with its traditional reliance on manufacturing, does not have a long tradition of entrepreneurship: The state ranks just 37th in the country in percent of self-employed workers.

So Michigan faces perhaps even more of a battle to develop an economic future that relies less on the swings in the auto industry, manufacturing and a number of large employers.

“We’re in uncharted water here. Nobody knows what happens next,” Lettieri said. If it makes Michigan feel better, it’s not alone, he added. “This is a national challenge.”

Changing gears

Plenty of economic development professionals in Michigan spent decades “chasing smokestacks” – trying to get the next large manufacturer to pick their town or county. It added value to the tax rolls, brought in decent jobs and yielded a net-plus for the community. Big business, like U.S. savings bonds, provided steady, reliable gains for millions of Michigan families from Detroit to Flint to Cheboygan.

That is, of course, is no longer true, and hasn’t been for some time, with the state’s manufacturing sector experiencing volatile swings in earnings and employment, despite occasional triumphs.

Not that the state is ignoring the problem.

In Lansing, economic development officials are trying to diversify that region’s economy.

“If you’re not embracing that entrepreneurial culture, you’re not going to be sustainable in the future,” said Tim Daman, president and CEO of the Lansing Regional Chamber of Commerce.

Daman noted that the vast majority of employers nationwide have 20 employees or less. That shift has forced a change in mindset.

While the Lansing chamber still chases factories, it is also nurturing a growing insurance industry and is looking to add new businesses around the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory and a yet-to-be-completed Facility for Rare Isotope Beams at Michigan State University. The particle accelerator will allow scientists from around the globe to conduct rare isotope research when it opens in 2020.

The chamber is anticipating the facility will also spawn related businesses in the burgeoning field of nanotechnology. with one study predicting the facility will create $1 billion in investment over its first decade.

Daman said the region is working to help would-be business owners get their start: There are seven business incubators in the region, where startups can share expenses as they try to build their nascent businesses.

Thinking through a business plan

But for new entrepreneurs to flourish in Michigan, they will need more than passion.

“There’s lots of ideas,” said Jackie Krawczak, president of the Alpena Area Chamber of Commerce, for new businesses. The problem, she and others point out, is a profound lack of understanding of what it takes to start and run a business.

So business leaders and banks get pitched ideas on lawn maintenance businesses and cupcake and coffee shops – with little attention to the economics of what it takes to survive in the shadow of the neighborhood Starbucks.

“Do you realize how many cups of coffee you have to sell to make it work,” Krawczak said she asks aspiring barista barons. Most do not.

What many people with business dreams don’t realize is the most basic of rules: No bank will lend you 100 percent of your start-up costs.

“If you don’t have a lot of cash to start, you can’t start,” said Shawn Preissle, a business consultant for the Small Business Development Center of Michigan, a federally and state-funded program to coach people considering start-ups.

Indeed, lack of capital remains one of the biggest impediments to new businesses, EIG’s Lettieri said. The Great Recession of 2007-09 took a huge chunk out of the traditional pillars of a start-ups’ cash: home equity, savings and lines of credit.

Housing values plummeted, saving rates fell with falling incomes and banks tightened lending requirements. Those declines hit Michigan particularly hard, with many people still owing more on their homes than they are worth and many others forced into early retirement by job losses.

Even if they surmount that hurdle, some new business owners don’t understand simple concepts like working capital and accounts receivable and experts say most have no idea how to write a business plan – the document that proves to any lender that your business is a well thought out venture and a safe risk for investment.

“Fifty percent- (of would-be business owners) just don’t understand what it takes,” said Preissle of the SBDC.

Luckily, that’s why she has her job – and why SBDC helps people across the state with offices in 10 regions.

Last year SBDC reported helping with the formation of nearly 350 businesses in Michigan that created or retained nearly 4,000 jobs.

The organization is one of myriad programs operated by the state and local entities, including universities and foundations, designed to foster economic development. There are accelerators (similar to incubators except the accelerator typically invests in the companies in exchange for equity in the business), loan programs and business pitch competitions (Grand Rapids, Lansing, Detroit, Ludington, and across the state), where prospective businesses “pitch” their ideas, hopping for seed funding. In Traverse City, organizations are pitching in, looking to foster new business and fund good ideas.

Peace, love and beer

Shannon Schwabe was a wedding photographer following a short career in logistics. Her husband Scott is a firefighter in St. Clair Shores, just north of Detroit. They were looking to start a business when Scott suggested a hop farm. An avid craft beer lover, Scott knew that local breweries were flourishing and they needed hops to make the beer – and most hops came from the West Coast.

Then Shannon saw a photo of a wedding at a hop farm, with a couple standing in front of the pine-tree shaped hops in the background.

Bingo! They hit upon the idea for Hoppily Ever After Farms a hop farm and destination wedding venue. They are growing hops; the weddings will come later, Schwabe said.

That led the couple to get help from Economic Development Alliance of St. Clair County – their farm is in the southern part of the county, just north of Algonac – and put their idea in the running for a business competition, GreenLight Michigan.

They won the top prize – $5,000 – at the regional event in Port Huron and went on to the state event in Lansing, where they competed against businesses pitching diagnostic medical strips, commuter ride-sharing software and high-tech outdoor gear.

Their competition, Shannon Schwabe said, was “trying to save the world. We just want peace, love and beer.” They did not win the big prize ($50,000) but used their $5,000 winnings to help them plant three acres of hops with plans to expand to 40.

Scott said he will remain a firefighter for now. Both have assumed the life of entrepreneurs, which can be hard.

“We just wanted to do something within our means and do something we’re passionate about,” Shannon said. Still, she knows it will mean delayed gratification – it’ll be a couple years before they can get the 1,000 pounds of hops per acre that will make them profitable – “and going a couple of years not seeing your friends and family.”

Dream for sale

In Roscommon, a small village east of Houghton Lake, downtown is a tidy mix of storefronts. A rail line cuts through town and when a train goes by a local bar bestows a free shot of booze on customers.

When Kurtis Norton first bought Village Hardware in town 16 years ago, every storefront was occupied. Not anymore. All across the several blocks of the main business district, a ubiquitous sign appears: “Dream for Sale.” It’s a realty sign marking an “opportunity” for a would-be business.

“We have so many open and close, open and close,” Norton said during a recent walk through town. “We’re a revolving door.”

Roscommon County lost nearly a quarter of its business establishments between 2006 and 2015, though overall employment was down just 12.5 percent. Norton notes the impact of big box stores, with the addition of a Home Depot and a Lowe’s nearby, taking a chunk out of his own bottom line (he owns another hardware store nearby).

What he doesn’t see are enough people who want to take the shot he did and invest. A couple storefronts have filled recently, but one is a nonprofit running a model train store and two are second-hand stores.

“Startups are hard,” said Andrea Weiss, manager of Roscommon’s branch of Chemical Bank, just a few blocks from downtown. Credit is tight these days, far tighter than it was when she started at the bank 35 years ago.

“It was a lot simpler back then,” she said. “I think 2008 scared a lot of people. It scared a lot of financial institutions for sure.”

And yet few people are coming in asking for startup money. She said the bank would have a hard time finding would-be entrepreneurs even if it suddenly had millions to invest. What they mostly get are people wanting to start landscaping and maintenance businesses – an income for that person, but not likely a jobs generator for the town.

Steely optimism

Jeff Drushal is old school.

Some of the machine tools he’s bought for his Jackson machine shop are older than him. But Drushal is an example of the entrepreneur that is willing to take an idea and make it a reality.

He always knew he wanted to own his own shop but developed his skills first while working for others. It wasn’t until he started planning a business for his wife – he said he’d put his own dreams on hold – that he realized he had the skills, the knowledge and the opportunity now.

Now he’s on the hook for rent in a small, 1,800-square-foot shop and when Bridge stopped by recently, he was welding a ladder for a boat. It was his first day and Drushal Fabricating had already taken delivery on the metal tubing that will be his first real job: Creating a railing for friend’s lake house.

Drushal is confident. But is he nervous?

“I honestly don’t know if I can afford to be nervous. I’m too focused on succeeding.”

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Jeff Drushal is betting on himself by opening his own metal fabricating business in Jackson, bucking a trend of fewer start-ups in Michigan. He hopes to employ a dozen workers in five years. (Bridge photo by Mike Wilkinson)

Jeff Drushal is betting on himself by opening his own metal fabricating business in Jackson, bucking a trend of fewer start-ups in Michigan. He hopes to employ a dozen workers in five years. (Bridge photo by Mike Wilkinson) Michigan businesses slow to recover: No state in the nation has as many counties that suffered steep declines in businesses as Michigan, where 12 counties lost 20 percent or more of their business establishments.

Michigan businesses slow to recover: No state in the nation has as many counties that suffered steep declines in businesses as Michigan, where 12 counties lost 20 percent or more of their business establishments. Roscommon economic development leaders created a program to help real estate agents sell local businesses, calling each empty storefront a “Dream for Sale.” It’s worked somewhat: a few businesses and a nonprofit have recently moved in. (Bridge photo by Mike Wilkinson)

Roscommon economic development leaders created a program to help real estate agents sell local businesses, calling each empty storefront a “Dream for Sale.” It’s worked somewhat: a few businesses and a nonprofit have recently moved in. (Bridge photo by Mike Wilkinson) Kurtis Norton, 42, came to Roscommon 16 years ago after buying Village Hardware. When he did, all the stores around him were occupied. Now, vacancy signs are all around as the village struggles to lure and keep businesses, a trend consistent across northern Michigan. (Bridge photo by Mike Wilkinson)

Kurtis Norton, 42, came to Roscommon 16 years ago after buying Village Hardware. When he did, all the stores around him were occupied. Now, vacancy signs are all around as the village struggles to lure and keep businesses, a trend consistent across northern Michigan. (Bridge photo by Mike Wilkinson) Jeff Drushal always knew he wanted to be his own boss and now, at 34, he’s giving it a shot. He’s welding a ladder here in his small space on Jackson’s west side. (Bridge photo by Mike Wilkinson)

Jeff Drushal always knew he wanted to be his own boss and now, at 34, he’s giving it a shot. He’s welding a ladder here in his small space on Jackson’s west side. (Bridge photo by Mike Wilkinson)