A different kind of house call: The doctor will see you now – remotely

Latrese Williams admits she’s “a bedside nurse at heart,” but at the end of the day, there’s no denying her new job is easier on her feet.

Williams, who once saw patients face to face, now sees them on a computer monitor, through a series of names and colored boxes and other data. Some of her patients are nearby, some aren’t, but none are in the John D. Dingell VA Medical Health Center in Detroit, where Williams works on a team practicing telemedicine.

It’s a burgeoning field that marries communications technology with health care, and is proving a boon to patients and care providers, who see it as a way to improve efficiency and expand access to medical care in hard-to-reach areas where a primary care doctor might be hundreds of miles away.

Telemedicine, its advocates say, is particularly suited for places like rural Michigan, where physician shortages are acute. While science hasn’t figured out a way for a doctor to feel your lymph nodes remotely, a patient can now use technology to show a dermatologist what a skin rash looks like. It enables a psychiatrist to assess your mental health via video link and prescribe medication. It can put a primary-care doctor in the Upper Peninsula in conference with a specialist downstate.

RELATED: In rural Michigan, a doctor shortage promises to get worse.

While the VA has been a telemedicine pioneer, the current, and likely worsening, shortage of doctors as well as nurses in Michigan makes rural areas of the state important partners in adopting telemedicine practices. Many now are.

“People might travel here to have cardiovascular or orthopedic care,” said Pamela Davis, system analyst for UP Health System Marquette, formerly Marquette General Hospital, in the largest city in the vast Upper Peninsula. “Some of them live six hours away. Why should they have to travel that far for a 15-minute follow-up visit?”

Davis said 15 hospitals in the Upper Peninsula, not all affiliated with the one in Marquette, now have secure videoconference lines where patients can interact with their doctors, sometimes alone, sometimes with a nurse in attendance (who can feel lymph nodes, and tell the doctor if they are swollen). Patients can have tests or X-rays done close to their homes, and have the results read, and diagnoses delivered, from afar.

This is, in fact, the most common sort of telemedicine, what Amber Mason-Dixon, chief nurse for specialty services at the Detroit VA, calls “clinical video telehealth.” It’s widely practiced within the VA system, in part because its patients frequently live far from a VA hospital. (In the lower peninsula, Saginaw has the northernmost VA hospital location, while U.P. vets are served by one in Iron Mountain.) However, the VA does have community-based outpatient clinics scattered around the state, and telemedicine is frequently relied upon between hospitals and clinics, Mason-Dixon said.

The VA uses telemedicine to keep tabs on patients with chronic conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure, with the latter set up with in-home devices that transmit data daily to nurses like Latrese Williams. The machines even do a bit of triage themselves, asking patients if they’ve remembered to take their medication, or if they might be wearing a tight shirt (which can restrict blood flow and distort a pressure reading) or under particular stress. If a later reading is less worrisome, Williams may not need to call.

But if she does, she’ll make some judgments via phone. Some patients, she knows, have difficulty with the equipment and frequently deliver erroneous readings. Others – including one patient recently who showed an emergency-level blood-sugar reading of 600 – are treated more aggressively; Williams might order a visit to a local urgent-care center.

Less acute patients, like Jesus Plaza of Shelby Township in suburban Detroit, get daily reminders to pay attention to their feet, where diabetic complications frequently announce themselves. Plaza may be asked for instance if he has any numbness in his toes, and told to remember to use a mirror to inspect his soles.

“It’s all done over the phone, with a machine,” Plaza, 78, said. “If I don’t answer, they keep calling, so you might as well pick up.”

Dr. Jed Magen, an osteopathic psychiatrist who teaches at Michigan State University’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, said these technologies are one solution to the chronic problem of physician shortages in rural areas.

“When I became chairman of the department, I would get calls from upstate, asking for doctors to be sent up,” said Magen. “Then it was, ‘Can you help us recruit?’ It’s hard to get doctors to move to rural areas, for lots of reasons. Professional isolation is a big concern.”

But telemedicine, sometimes practiced in partnership with other health-care professionals in the patient’s area, allows downstate psychiatrists to evaluate patients hundreds of miles away. The process runs through a secure video link, and is similar to an in-person visit, Magen said – doctor and patient introduce themselves, and the exam begins.

“It’s not quite like being there, but it’s pretty close,” said Magen. “The quality of care is comparable.”

Could state do more?

Technology offers powerful tools in a state with shortages of at least one primary care speciality doctor in three out of four Michigan counties, according to the Citizens Research Council of Michigan. But one health expert said he believes the state could do much more to encourage telemedicine’s growth in hard-to-reach regions of Michigan.

“The ironic thing for Michigan is, we have a techie for governor, but he has yet to make a gesture or effort to see how this technology would help the state,” said Dr. Rashid Bashshur, senior advisor at the University of Michigan’s e-Health Center.

Actually, in 2012, Snyder signed into law an amendment to the insurance code to accommodate telemedicine, and encourage its development. The new law establishes parity between traditional and telemedicine for insurance purposes, meaning insurers must reimburse remote medical treatment the same as in-person practice. This was an important step, but, Bashshur said, the field could use more official encouragement from Lansing.

“Policymakers need to do what other states have done: Promote development of a network of telemedicine services, and invite all to participate. We could build a statewide network with multiple centers of excellence, connecting throughout the state,” Bashshur said, naming others that he said are forging ahead in these efforts -- Georgia, Arizona, California and others.

For example, Michigan has struggled with chronic obesity, a treatment area telemedicine is ideally suited for, Bashshur said. In the VA system, overweight patients are monitored at home with connected scales, and meet with nutritionists and attend support-group meetings via teleconference. Encouragement to eat sensibly arrives via email and text message around mealtime.

“An active telemedicine network would serve us well in reaching young people and (with) weight management interventions,” Bashshur said. “I would like to see the University of Michigan Health System ahead of Mayo Clinic. But the latter has a far more active program than we do.”

Part of the problem, Bashshur conceded, may lie with doctors themselves, who have not aggressively pushed for such a network. The Michigan State Medical Society supports the credentialing of remote doctors by the hospitals where patients are treated, said MSMS spokesman Kevin M. McFatridge, but doesn’t otherwise have legislation or other policy initiatives before lawmakers now.

Technology gallops ahead

Amber Mason-Dixon, chief nurse for specialty services at the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, stands in a conference room set up for a telehealth session promoting weight loss. Patients gather in this room and see presentations from an array of health-care professionals, with whom they can interact. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

Amber Mason-Dixon, chief nurse for specialty services at the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, stands in a conference room set up for a telehealth session promoting weight loss. Patients gather in this room and see presentations from an array of health-care professionals, with whom they can interact. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

Telemedicine evolves quickly, leaving many docs confused on where they stand legally, said Louis Szura, an Oakland County lawyer with a specialty in health-care law. As the field blossoms, “technology outpaces everything, and the culture is behind it, and the law drags behind that,” he said. The potential conflicts with existing legal and ethical codes are numerous.

Privacy, for instance, is an obvious concern. Video teleconferencing lines need to be secure. Skype, FaceTime and other mass-market video links aren’t compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (commonly known as HIPAA) privacy standards.

Licensing is another potential landmine. Can a psychotherapist in Michigan treat clients vacationing in Florida? (Probably not, unless the therapist is fully licensed in Florida, or if certain narrow exceptions apply, Szura said.)

Some states are starting to respond to these questions, he added. Minnesota recently added a special physician’s medical license applying to telehealth, as have a few other states.

Besides licensing and privacy, there are even more perplexing issues for policymakers and the medical community to hash out, Szura said. What if a teleconference link goes down mid-session? Might a treating physician have a responsibility to call 911? What if a bad connection leads to a patient misunderstanding a treatment plan or drug dosage; is a doctor liable? All will have to be addressed for telemedicine to take hold.

“Personally, I have talked to physicians, and they’re fascinated by the idea,” said Szura. “It’s just complicated, though.”

Which raises the question: How prevalent is telemedicine in Michigan? The e-Health Center at the University of Michigan is growing busier “almost by the week,” Bashshur said, but he has no data to suggest how quickly the practice is spreading around the state.

Latoya Thomas, director of the State Policy Resource Center at the American Telemedicine Association, said the 2012 parity law puts the state on the right track.

“In medicine, the challenge is payment,” Thomas said. “Is there room for improvement? Probably.”

Thomas said an ideal situation for doctors would be for legislatures to “get out of the way” of the advancing field and “just let it happen seamlessly. ...It’s not one technology, it’s a way of delivering care.” Recognize that, and adoption will spread.

The doctor will text you now?

Professionals like Mason-Dixon see the possibilities everywhere. On a rotation through a VA intensive-care unit in Alabama, she participated in a training exercise in which a virtual patient was put through a cardiac-arrest crisis with the emergency treatment directed in real time by a doctor in Cleveland.

“Everything can’t be done with telehealth,” she said. “It’s not meant to replace traditional medicine. But it can cut down on drive time. It can save resources for patients – gas, time, etc. And with less acute cases being treated this way, it frees up space for the people who must be seen in person. It improves efficiency.”

George Kipa, medical director for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, said BCBSM has been paying telemedicine claims since 2002, and processes about 2,000 claims a year. Medicaid and Medicare had required telehealth patients to receive treatment at approved centers, but Medicaid has dropped that requirement and increased reimbursement for telemedicine claims.

As the technology adapts and improves, the potential for improving health care in areas like rural Michigan is promising. Much depends on improvements in rural broadband access, but there’s no reason not to be optimistic, said Szura, the lawyer.

“This is something that reduces cost and increases access to care,” he said. “It increases patient choice, but we need more providers into the system. If we can get more providers, patients will follow, and they’ll love it.”

Some cost skeptics

Not everyone believes more reliance on telemedicine will reduce overall healthcare costs, noting that the practice could make seeking out health care too easy. Dr. Ateev Mehrotra, a Harvard Medical School health-policy researcher, told the New York Times recently that “it’s very plausible, and probably likely, that a lot of people who do a virtual visit would otherwise have stayed home” rather than take the trouble to visit a doctor’s office.

Williams, the Detroit VA nurse who now spends much of her day in a cubicle in an office, still likes to spend a few hours a week working on a ward in the VA hospital.

“It keeps my skills sharp,” she said. “But my body is glad I’m not doing it all the time now.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Latrese Williams, a nurse at the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, monitors patients remotely via telemedicine. Her caseload includes hypertension, diabetes and other chronic conditions that can be tracked with devices in patients' homes and delivered to her desktop computer. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

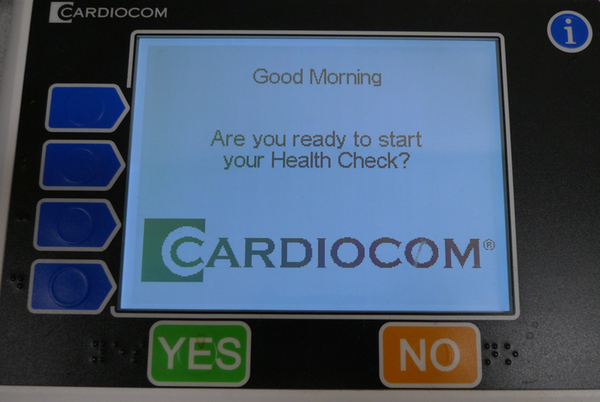

Latrese Williams, a nurse at the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, monitors patients remotely via telemedicine. Her caseload includes hypertension, diabetes and other chronic conditions that can be tracked with devices in patients' homes and delivered to her desktop computer. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer) Patients participating in VA telehealth programs commonly get a device like this in their home. Data is transmitted to an overseeing nurse, who will follow up with a phone call if the patient’s vital signs are troublesome.

Patients participating in VA telehealth programs commonly get a device like this in their home. Data is transmitted to an overseeing nurse, who will follow up with a phone call if the patient’s vital signs are troublesome.