6 reasons why students at some high schools are better prepared for college or career

Earlier this month at West Ottawa High School, near the shore of Lake Michigan, Principal Todd Tulgestke did his best to make an impression on next year’s high school freshmen.

Using numbers big and small, Tulgestke talked about lifetime earnings and how decisions the students make now can have a profound impact on how much they can earn decades later. The bottom line: To make yourself better, you get a college degree. Or learn a trade. And you keep learning even after you earn your high school diploma.

At a school where more than 4-in-10 live in poverty, the dream of a breezy walk across a leafy college campus may seem like fantasy to many students. Tulgestke wants the kids to think it’s their reality. The district has a full-time college guidance counselor and even brings in college aid officials to help students and their parents fill out vexing financial aid forms.

“That is our mission,” Tulgestke said, “that they believe they will go to college after they graduate from West Ottawa High School.”

West Ottawa High did not quite rise to the level of Academic State Champ this year. But it is a high school that has made great strides, given its poverty level, in preparing graduates for the rigors of college and giving them the tools to succeed once there. Propelled by administrators like Tulgestke and a college-striving culture that includes counselor training and a full-time college advisor, West Ottawa is better preparing students for college or certificate programs, skills considered essential these days to earn a solid, family supporting income.

Nearly 57 percent of West Ottawa High School grads had finished their higher education or were still pursuing a degree four years after graduating from high school, most recent education data show. The average for schools with similar levels of poverty: 42 percent.

“They are committed to building a college-going culture in real tangible ways,” said Brandy Johnson, executive director of the Michigan College Access Network, which advocates for higher education, particularly for poor students or students from families that never before sent a child to college.

MCAN not only trained every West Ottawa counselor, it helped pay for the school’s full-time college advisor, a rarity at many high-poverty Michigan high schools.

Success across the state

The Academic State Champs high schools have all shown a proven ability to prepare students for success after graduation -- their students are more likely to attend a two- or four-year college or university, or enroll in a program that produces a post-high school certificate or credential.

They are also more likely to complete what they start within four years, setting themselves up for the higher incomes and steady jobs that typically come with higher-education degrees.

The champs range from tiny Harbor Beach High School along Lake Huron in the state’s Thumb to Melvindale High School in an inner-ring suburb of Detroit; from both Kalamazoo high schools (Loy Norrix and Central) in west Michigan to Ironwood (Luther Wright K-12 School - High School) in the Upper Peninsula. They include affluent schools like those in Troy, Birmingham (Seaholm and Groves) and East Grand Rapids and magnet schools in far less wealthy parts of Grand Rapids and Saginaw.

What are some factors that they have in common? Here are a few:

1) Money matters

The most obvious takeaway is also the most sobering: poverty too often largely predicts student success both before and after high school graduation.

At the top school in the state, Troy High School, just 8.3 percent of students tracked over several years were eligible for a federally subsidized lunch. The school with the fewest poor students (3.4 percent), was Northville High and it was No. 2 on our list state champs schools.

Schools with higher levels of poverty did markedly worse than those with little to no poverty. That is hardly surprising since students from higher-income families have more resources (access to computers, tutors, college and test prep classes, etc.) and more college-educated role models to lean on as they pursue higher education.

Bridge found that for high schools with small populations of poor students, 25 percent were considered college-ready in all four ACT testing subjects as high school juniors, compared with only 6.5 percent in the state’s poorest public high schools.

At the most affluent schools, 82 percent of graduates enrolled in some form of higher education (two- or four-year colleges, but also certificate programs like cosmetology or auto repair) compared with 59 percent at the poorest schools.

The biggest gap came four years later, when 71 percent of graduates from more affluent high schools had a college degree or certificate, or were working on one. At the poorest schools, just 42 percent were still on that path.

“Everybody knows the impact of poverty on educational outcomes” through high school, said Johnson of MCAN. “and post-secondary it’s no different.”

2) College counseling opens doors

As a state, Michigan provides one school counselor for every 732 students, fourth worst in the nation. Counselors are stretched so thin, particularly at low-income schools, that many have little time to help individual students find their right path after they graduate from high school.

Indeed, Michigan, which has a lower percentage of adults with a college degree than the national average, does not even require school counselors to be trained in college and career navigation. Recent efforts in Lansing to add that requirement have yet to succeed. One recent bill would have required 25 hours of such training; it passed the House but the state Senate did not take up the bill.

It’s a situation recognized by MCAN and others, which have helped to fund full-time advisors at a number of schools and trained many counselors, including some at five of the schools that finished in the top two tiers of Academic State Champs.

It’s helped schools like West Ottawa, where first generation students don’t always know or can’t imagine the possibilities if there are not experienced counselors their to steer them.

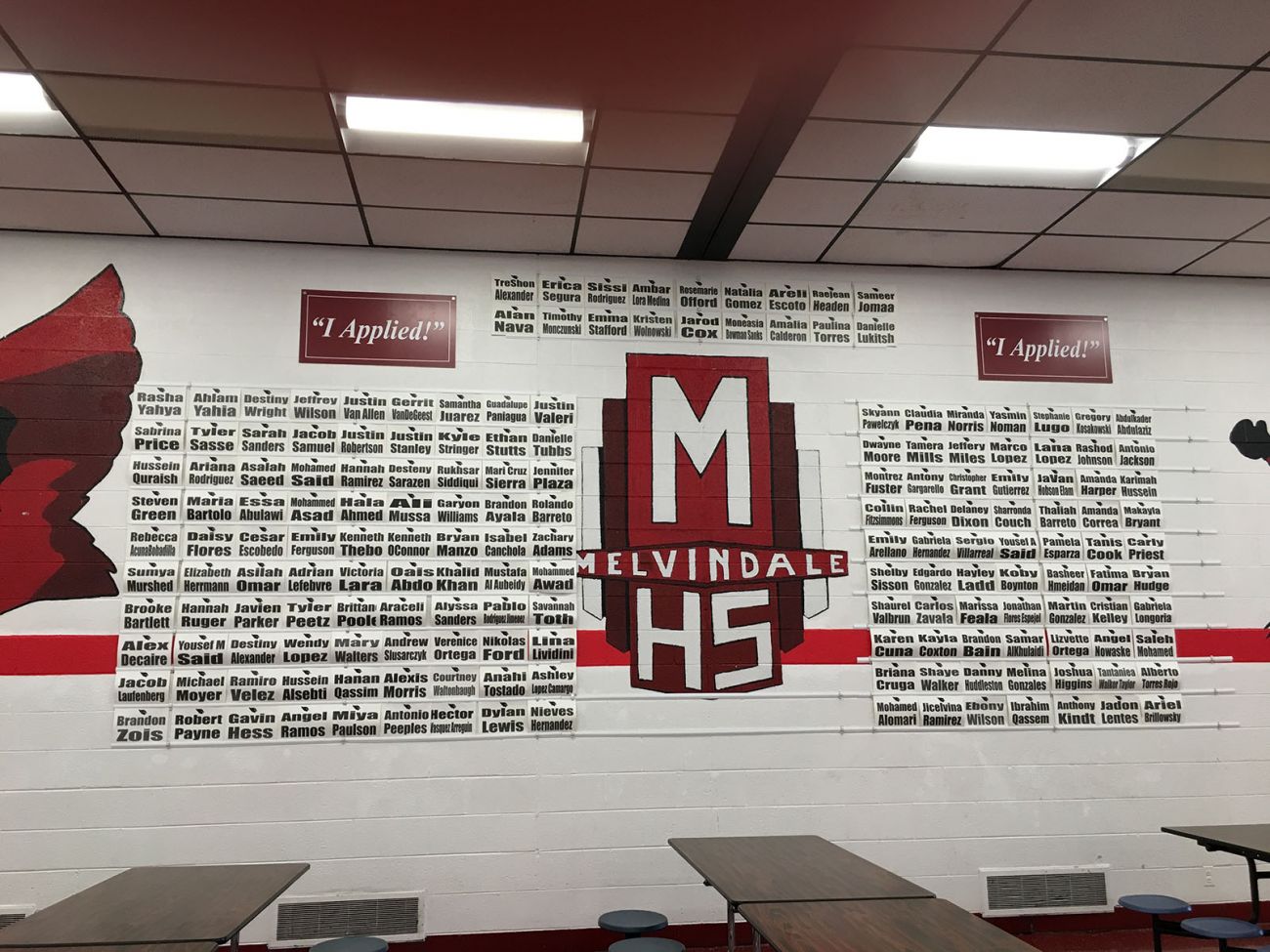

And it’s helped at Melvindale High School, southwest of Detroit, where 62 percent of the students are eligible for a subsidized lunch. The school’s strong push to increase college enrollment paying off. This year, Melvindale is an Academic State Champ.

“For each of the last two years, 100 percent of their students have applied to college,” Brandy Johnson said.

3) Magnet schools

Some schools naturally skewed toward larger populations of high-achieving students. Several of this year’s Academic State Champ schools were magnet schools: in Saginaw (Arts and Science Academy), Grand Rapids (City/Middle High School) and Detroit (Renaissance High School), for instance.

Each has limited openings based on past performance, citizenship and test scores. As a result, each also has different demographics than its district at large: At City/Middle High in Grand Rapids, 36 percent of students were poor, less than half the poverty rate of other city high schools.

The Saginaw Arts and Science Academy student body is far less poor than students in the rest of the Saginaw district. And in Detroit’s impoverished public schools, where more than 70 percent of high school students were in poverty, the rate at Renaissance was 40 percent.

4) Promise programs show promise

In Kalamazoo, both public high schools were champs, bolstered by higher college enrollment and post-graduation progress by graduates. More than 82 percent of graduates at both schools enrolled in college or certificate programs – the average for schools with similar poverty levels was 59 percent.

And far more received a degree or certificate or were still working toward completion four years later: 66 percent at Kalamazoo Central and 60 percent at Loy Norrix (the average for similar schools was 42 percent).

That success is likely attributed to the Kalamazoo Promise, a nationally recognized scholarship fund – bankrolled by anonymous donors – which pays in-state college tuition for all graduates. One study showed that the scholarships have led to substantially higher college enrollment.

Similar programs, though none as generous as the one in Kalamazoo, exist around the state, including in Detroit, Battle Creek, Saginaw, Hazel Park, Muskegon and Grand Rapids.

5) Keep coaching at college

One of the best ways to improve college graduation rates is to close the graduation gap between lower-income students and their wealthier peers.

In many cases, the solution is more intensive help on college campuses for those of lesser means: campus coaches, mandatory tutoring, a tailored curriculum designed to keep them on schedule and in school.

“That’s absolutely critical,” said Dan Hurley, CEO of the Michigan Association of State Universities, which represents the state’s 15 public four-year schools.

Indeed colleges and universities in Michigan and across the country are doing more to help at-risk students in part because pilot programs have shown great promise in New York and Ohio. Bridge will detail many of these programs in our next edition.

6) Many paths to success

For most students, the top goal is a college degree. But in some Michigan high schools that ranked high in this year’s Academic State Champs, a larger proportion of students earned a certificate after high school – training for jobs such as a hairdresser, nurse’s assistant or information technology worker.

At Battle Creek Central High School, nearly 11 percent of grads got a two-year degree or a certificate, and at nearby Homer Community High School, nearly 17 percent did.

Graduating, but not prepared

But Bridge’s ACS analysis also showed that a number of high schools are generating too many grads who aren’t getting postsecondary degrees, in part because they simply weren’t ready for the demands of higher education.

At 16 schools in our analysis, more than half of those who pursued post-secondary education still needed to take remedial classes after high school, Bridge’s analysis of state data showed, classes that students pay for yet generate no college credit.

At Arthur Hill High School in the Saginaw school district, half of those who enrolled in a postsecondary program needed remedial help. In the same district, the Arts and Science Academy, a magnet school, had 34 percent of graduates ready for college, compared to 5.1 percent for Hill; nearly 95 percent of the magnet school’s students enrolled in higher ed, compared to 61 percent at Hill.

But the biggest gap appeared four years later: More than 81 percent of the academy’s grads had a degree or were still in college, compared with just 36.8 percent of those graduating from Arthur Hill.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!