Betsy DeVos’s Michigan legacy

It’s clear how Betsy DeVos wants to change public education.

It’s equally clear how hard Donald Trump’s nominee for U.S. Secretary of Education will push, and how much she’ll spend, to make those changes.

What’s less clear is whether her remedies for public education -- unveiled in Michigan over more than two decades -- actually help students learn.

The academic rank of Michigan students compared with peers in other states has dropped dramatically since DeVos’s biggest policy victories: the expansion of charter schools (most run by for-profit companies), and breaking down barriers to students attending schools outside their home district, known as school choice.

Even her critics laud DeVos for her guiding principles -- that all students deserve access to a quality education and shouldn’t be trapped in a failing public school.

But DeVos’s dogged commitment to policies that have yielded, at best, mixed results in Michigan raises questions about what lessons she would take to Washington, as well as about her willingness to listen to viewpoints outside her free-market ideology.

Ideology and test scores

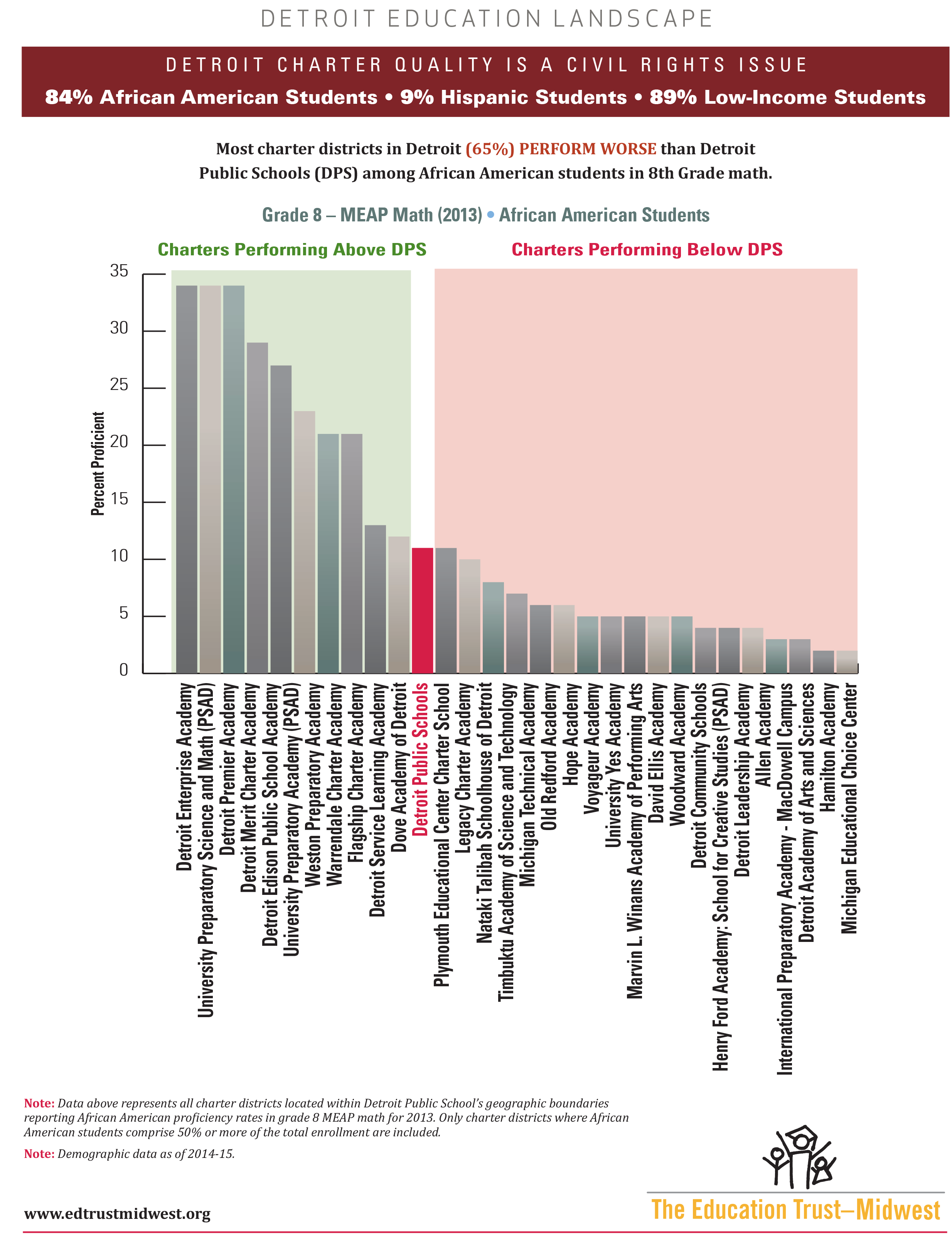

Perhaps the best example of Betsy DeVos’ impact on state education policy can be seen in Detroit, where today just one-in-four of the city’s students attend Detroit Public Schools. About 46 percent attend charters, the majority of which are in the city, with other students traveling to classes in districts outside of Detroit -- policies that are the hallmarks of DeVos’s K-12 orthodoxy.

Her influence in Detroit was seen most recently in May, when the the House and Senate squared off on a proposed plan to reorganize and the state-controlled Detroit Public Schools and rescue it from a crushing debt of $750 million.

The state Senate passed a rescue plan that mirrored a proposal hammered out by a bipartisan group of legislators, educators, Detroit leaders and foundations. That proposal would have created a Detroit Education Commission with the power to approve or deny locations for new schools in Detroit, including charters.

Such monitoring is common in most states that allow charter schools. But giving a government body oversight over charters is anathema to Michigan’s powerful charter school industry, and to its most powerful benefactor, DeVos.

That’s true even in Detroit, with the nation’s worst big-city test scores, where some charters are excellent, but most have test scores that are about the same or worse than the city’s traditional public schools. In 2013-14, 70 percent of Detroit’s charter schools ranked in the bottom quarter of all Michigan schools, according to the Education Trust-Midwest, a nonprofit education policy and advocacy organization.

Even so, DeVos and her powerful lobbying group, the Great Lakes Education Project, or GLEP, lobbied to kill a commission they feared would inhibit charter growth.

Tonya Allen, president and CEO of the Skillman Foundation, which played a lead role in organizing the coalition of leaders that drafted the proposal, said she recalls Republican members of the House being called in to closed-door meetings with GOP leadership. One by one, Republicans who had previously been in favor of the Detroit Education Commission emerged from meetings to say they were now against it.

Within two months of those closed-door meetings, GOP lawmakers and the state Republican Party received $1.45 million in donations from the DeVos family.

By June, a $617 million rescue plan passed, but the DEC was no longer a part of it, leaving the city still without oversight of charters.

What is surprising about that story is not that a wealthy, politically active woman influenced public policy, but that DeVos put her stamp on the schools of a city that, by Allen’s account, DeVos said she knew little about. Allen told Bridge she had traveled to West Michigan in 2014 to seek DeVos’s advice on how to improve Detroit’s failing public schools. According to Allen, DeVos demurred, saying, “I don’t know Detroit.”

"We won the public policy debate over whether (school choice) is working or not,” Allen said, but “GLEP won the politics.”

A powerful influencer

DeVos, who declined to be interviewed for this article, wins in no small part because of her ability and willingness to write big checks.

Born Elizabeth Prince, DeVos, 58, was born into privilege. Her father founded a lucrative auto parts company, and her brother founded Blackwater USA, the private military and security firm that faced controversy for its contracting work for the U.S. government in Iraq.

She and husband, Richard “Dick” DeVos, an heir to the Amway fortune, donate generously around Grand Rapids and nationwide (including $22 million to the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts.) Betsy DeVos toiled for years in the state and national Republican party, rising to lead the state party twice. She is chairwoman of The Windquest Group, an energy technology firm. The power couple has held fundraisers for presidents and invested in causes ranging from a think tank, evangelical groups and political action committees to a right-to-work crusade and anti-tax ballot measures.

But in no area of public life have Betsy and Dick DeVos made more of an impact than in Michigan schools. Neither has a professional education background, and Betsy and her children did not attend public schools. She has nevertheless used her pocketbook and political influence to reshape the state’s K-12 landscape.

Over the past decade, in its crusade to expand and protect charter schools from regulation, the DeVos family has donated at least $6.1 million to the Republican party and state lawmakers, according to the Michigan Campaign Finance Network, a nonpartisan group that monitors the role of money in Michigan politics. The Republican legislature’s lifting of restrictions on Michigan charter schools led to a glut of schools, especially in poor communities like Detroit.

Today, there are more than 300 charter schools in Michigan, more than double the number in 2000. Michigan also has far less government oversight than in most states, little leverage to close or demand improvement from charters, and has the highest-percentage of charters run by for-profit companies in the country.

But while the traditional public school establishment focuses on charters’ lack of accountability, DeVos has effectively turned the focus on the establishment's failures.

“We believe that the only way that real education choice is going to be successfully implemented is by making it a bipartisan or a non-partisan issue,” DeVos said in 2013. (The whole interview can be read here.) “Until very recently, of course, that hasn’t been the case. Most of the Democrats have been supported by the teachers’ unions and, not surprisingly, have taken the side of the teachers’ unions. What we’ve tried to do is engage with Democrats, to make it politically safe for them to do what they know in their heart of hearts is the right thing.”

Doing the right thing is often prodded by money.

In the last two years alone, Betsy and Dick DeVos and other DeVos family members donated $3.4 million at the state level. That’s more than was donated by the United Auto Workers and the Michigan Education Association (the state’s largest teacher union) combined.

“The DeVos family is a political donating force unlike anything else in Michigan,” said Craig Mauger, executive director of Michigan Campaign Finance Network. “We don’t know what’s in a lawmaker’s mind to make an ultimate decision. We do know this family has gotten what they wanted and this family is the number one donor to a lot of lawmakers and groups making the decisions. Those are the facts we know.”

“The DeVos family is a political donating force unlike anything else in Michigan,” said Craig Mauger, executive director of Michigan Campaign Finance Network. “We don’t know what’s in a lawmaker’s mind to make an ultimate decision. We do know this family has gotten what they wanted and this family is the number one donor to a lot of lawmakers and groups making the decisions. Those are the facts we know.”

Eileen Weiser, a Republican on the State Board of Education who was recruited to run by Betsy DeVos in 1998, said the state is better for DeVos’s influence.

“She passionately believes that every child deserves a quality education regardless of income level or home zip code,” Weiser said. “She supports quality schools, whether public or private, traditional or charter, online or located nearby in schools of choice.

“While working with her I've watched her call for debate; listen attentively; propose initiatives that can improve student learning; and then work through all obstacles to implement good strategies for children.”

A price of dissent

Listening, debate and being open to others’ ideas all seem like good characteristics for the nation’s top educator. But that wasn’t Paul Muxlow’s experience with DeVos.

A Republican from Brown City, in Michigan’s thumb region, Muxlow was elected to the state House of Representatives in 2010 and is considered a conservative on most issues. “I toed the line” on DeVos policy proposals, Muxlow said. “I voted right along with my fellow conservatives.”

With one exception.

In December 2011, Muxlow voted against removing the cap on the number of charter schools that can operate in the state.

“I have 10 school districts I represent,” Muxlow said. “All of them are little, local public schools, from 500 students to a couple thousand. When the vote came along, I simply said, ‘I would support (more charter schools) in areas where there are failing (traditional public) schools. But if you put a charter school in my little part of the thumb of Michigan and take 25 kids out of the school, you’re really putting them in bad shape.’”

The bill still passed the House 58-49, with Muxlow voting no. The bill also passed the Senate and was signed into law by Republican Gov. Rick Snyder.

Even though the bill passed comfortably, GLEP, which is primarily funded by the DeVos family, spent $184,000 to try to defeat Muxlow in the Republican primary in 2012.

It shouldn’t have been a surprise. Betsy and Dick DeVos have been candid about the cost of not supporting their charter and school choice policies.

“I’ve voted for almost everything the DeVoses wanted,” Muxlow told Bridge. “I’d walked a parade for Dick Devos when he ran for governor (in 2006). And then they ran the dirtiest campaign against me. The Devoses took it upon themselves to try to beat me.”

Muxlow won that primary by just 137 votes, but he said the money spent against him in the primary had a chilling effect on fellow legislators who feared the steep price they would pay for disagreeing on education policy with the DeVos family.

“The DeVoses run K-12 in Lansing,” Muxlow said. “I don’t think it’s a secret. They’re all in on charters, and there’s skimpy little difference in performance in most cases.”

Michigan’s steady fall

Charter schools, originally sold to Michigan residents in the mid-1990’s as a way to improve student learning and bring innovation to the state’s staid public school system, have performed roughly on par with the state’s traditional public schools, with some excelling and many others average or struggling.

A Bridge analysis of 2014 test scores adjusted for student poverty levels found that some charters were among the highest-performing schools in the state, but even more were among the worst. About 31 percent of charters were in the bottom quarter in academic performance when poverty was taken into account, compared with 24 percent of traditional public schools.

In 2000, Michigan students scored above the national average in 4th grade math and English and 8th grade math and English on the National Assessment of Educational Progress test, known as the nation’s report card. By 2015, Michigan was below the national average in 4th grade math and English and 8th grade math, and was at the national average in 8th grade English. Michigan is ranked in the bottom 10 states for fourth-grade reading, a key indicator for educational success.

Those plummeting rankings are likely the result of many factors, but it’s undeniable that choice and charters haven’t stopped the slide.

“It’s hard for me to get mad at anyone who’s in the game to try to make the lives of children better, compared to people who sit on the sidelines and point fingers, even if we disagree,” said Michigan School Superintendent Brian Whiston. “I support choice and charters, but that’s been the philosophy for 20, 25 years, and it hasn’t improved education.”

Echoing others, Whiston said innovation has to be matched by demonstrated success. “I would like (the state’s) choices to be (informed) by research on what we’ve learned works,” he said.

Gary Naeyaert, executive director of GLEP, acknowledges that Michigan is “not doing better (academically) than we were 20 years ago,” when there were fewer charters and much less ability to choose what school your child will attend.

But he contends that school choice and charters are “not the cause” of the state’s school struggles. Instead, he blames a “dramatic lack of accountability” in failing traditional public schools and poor communication with parents about the difference in quality between schools. “There are three legs to the stool, and choice is just one of them,” Naeyaert said.

Naeyaert also notes that while charters have had mixed success, a study from Stanford showed that students attending Michigan charter schools on average “gain an additional two months of learning in reading and math over their (traditional public school) counterparts,” and an additional three months in Detroit.

As it happens, one of the state's more successful charter schools was founded in 2010 by Dick DeVos, with Betsy's encouragement. This year, the 490-student West Michigan Aviation Academy in Grand Rapids was ranked among the state's best high schools when adjusted for poverty by Bridge Magazine's Academic State Champs.

Too much choice?

Detroiter Roosevelt Bell is the kind of parent Betsy DeVos probably has in mind when she promotes school choice. He took his daughter out of Detroit Public Schools after two years of waiting fruitlessly to see upgrades to subpar facilities. He passes by two nearby traditional public schools near his home to take his daughter to the Detroit Service Learning Academy, a charter school founded by the YMCA.

Bell said he knows there are good and bad in public and charter schools because his daughter has attended both. “I didn’t want to be pigeon-holed into taking my child to a school I didn’t like or she didn’t feel comfortable in,” Bell said. “If I like the school two miles down I’m driving my daughter there.

“Choice is comfortable for parents because now you can pick and choose.” Bell said. “All we want is to be able to have a choice. That should be what every American wants, to have a say so in the matter.”

Detroit parent Arlyssa Heard has a different story. She has enrolled her sons in traditional public, private and charters schools over the years. Her 11-year-old son is now a fifth grader at the James and Grace Lee Boggs charter school, which she likes for the individualized instruction her son gets.

She said Detroit parents have plenty of choices, but lack quality choices. Competition has led Detroit’s public schools to close more than two-thirds of its buildings, leaving some neighborhoods underserved by schools and others teeming with too many.

“How much time have the DeVoses spent inside some of these homes with kids who go to three to four different schools? Or kids who are trapped in neighborhoods where there’s only one school left?” Heard asked.

“There are some kids trapped in neighborhoods with no schools because parents don’t have a car or are working too many jobs and don’t have the wherewithal or know how to navigate the chaos. Yet we hear from the DeVos family that parents want choice,” Heard said. “We want choice, but we want quality choice right in my neighborhood. I want good choice. I don’t need six different principals in three years … or a school closing a week before school starts,” she said, referring to University Yes Academy, a westside charter that shut down its high school days before school started this fall.

Sandy Baruah, leader of the Detroit Regional Chamber of Commerce, is a well-connected Republican who is similarly torn. He’s uncomfortable with the lax oversight and disparate quality of charter schools in Detroit, but also knows that many parents are happy to have choices for their kids.

The DeVoses “were instrumental in bringing the ability to charter schools to the state of Michigan,” Baruah said. “Every parent who has found a good charter school option in Detroit to send their kid to should be thankful.”

Choice goes up, test scores go down

Sarah Lenhoff, an assistant professor in Wayne State University's College of Education, is among a team of researchers studying the effects of open enrollment school choice programs. She said charter schools in Michigan do not live up to the promises made when they were legalized in the 1990s, unlike states where charters schools are more regulated.

“The initial impetus for charter schools was to provide an element of competition with traditional public schools. If you had to compete for students, the logic is, schools will come up with unique curriculum designs that will improve all schools,” Lenhoff said.

“What we’ve seen in Michigan is somewhat of an open, completely free market where there’s very, very little regulation,” Lenhoff said.

And, too often, inadequate information.

A study conducted by researchers at Michigan State University found that students who moved to another school district through schools of choice policies didn’t improve their test scores. There may be other benefits for students taking advantage of school of choice policies, said study author Josh Cowen, associate professor of education at MSU, such as perceived safety or social issues.

But if schools of choice is a policy aimed at improving learning, it hasn’t worked.

“Some people confuse means and ends in education, and that can be a problem,” said Michael Rice, superintendent of Kalamazoo Public Schools. “Choice is at best a means to an end of higher student achievement, it’s not the goal itself. And we’ve had choice for over 20 years in the state, and our (academic) ranking (among states) has declined substantially.”

Another Bridge analysis of schools of choice data found the policy had the unintended consequence of increasing segregation in some districts. The analysis found that students, both white and black, are more likely to move to districts that are less diverse than their home districts.

“I have no doubt they believe what they are promoting is good,” said Vicki Markovich, who recently retired as superintendent of Oakland Intermediate School District, of the DeVoses’ education policies. “Unfortunately, their efforts have focused on a very narrow view of education.”

Michigan stands alone

There are lessons that can be learned from other states that get beyond the ideological battles that have sometimes stymied meaningful reform in Michigan. In 2014, Bridge visited four high-performing or fast-improving states to see how they are making gains in education.

Some of those states have strong teacher unions and others do not. Some have robust charter schools, others don’t. Some spent more in education than Michigan, others less. Some were red states, others were blue. What they shared was a bipartisan commitment to high academic standards, teacher training and a willingness to put money where it’s needed most – supporting low-income and other high-risk students.

More coverage: What Michigan schools can learn from leading states

and Massachusetts charter schools are few but mighty

Massachusetts, long the model for public school education in the U.S., has outstanding charter schools. But there are a small number of them, and they are highly regulated by the state. Last month, voters there overwhelmingly rejected a ballot measure that would have allowed for the broad expansion of charter schools.

“I hope she looks at what’s worked in other states,” Markovich said of DeVos. “Providing quality education is complex. When you’re working in a field, trying to work around the issues of poverty, it can’t be fixed with a single solution.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Students at the AGBU Alex & Marie Manoogian Academy charter school in Southfield, outside Detroit, in 2012. (Bridge file photo)

Students at the AGBU Alex & Marie Manoogian Academy charter school in Southfield, outside Detroit, in 2012. (Bridge file photo) One example of the weak oversight of charter schools in Michigan is Detroit Community Schools, a charter where school leaders didn’t have state-required certifications,

One example of the weak oversight of charter schools in Michigan is Detroit Community Schools, a charter where school leaders didn’t have state-required certifications,  Michigan Rep. Paul Muxlow, R-Brown City, said he felt Betsy DeVos’s wrath when he opposed unfettered charter expansion in the state.

Michigan Rep. Paul Muxlow, R-Brown City, said he felt Betsy DeVos’s wrath when he opposed unfettered charter expansion in the state.