How a single, powerful senator killed serious reform of teacher evaluation

On a warm day in Ann Arbor in August 2013, a small group of educators attended a cookout at the home of Deborah Loewenberg Ball, dean of the University of Michigan School of Education.

For two years,the group had gathered at the behest of the Michigan Legislature to research teacher evaluation systems from around the nation, looking for ways to improve classroom teaching in Michigan. They’d just published an exhaustive report they believed would help turn around Michigan’s flailing public schools, which had fallen to the bottom rung of schools nationally. With their work done, the group expected their recommendations would soon be made into state law. There were brownies, toasts and pats on the back.

“I remember saying we should get back together in a few months when the bill passes,” David Vensel, principal of Jefferson High School in Monroe, said recently of the work of the group, known as the Michigan Council for Educator Effectiveness.

“Now, it’s two years later.”

Today, the group’s cutting-edge efforts to improve teacher accountability, which seemed like a sure bet as recently as five months ago, have been essentially gutted. A central provision of their recommendations – to rid the state of its patchwork of local, often useless evaluation models in favor of rigorous statewide criteria – is gone from a new bill now before the House. Even some who support the watered-down bill privately admit it likely will do nothing to improve education for Michigan students.

The new bill, created and championed by Sen. Phil Pavlov, R-St. Clair Township, would allow local school districts to continue to create their own standards for evaluating teachers, despite the recommendations of Ball’s group, despite research showing the benefits of tougher, more consistent standards in other states, and despite a clear public mandate for increased teacher accountability.

“Quality is a statewide issue,” said a frustrated Sen. Margaret O’Brien, R-Portage, a fervent supporter of more rigorous evaluation standards. “When it comes to evaluations, we need to have statewide standards.”

This is the story of how a critical education reform, which enjoyed broad support among state education associations, education experts, the governor’s office and legislators in both parties, was undone by a lone lawmaker ‒ Phil Pavlov, the powerful chairman of the Senate Education Committee.

MORE COVERAGE: Ball Q-and-A: Michigan kids ‘will lose’ with weak teacher evaluation bill

Bridge Magazine interviewed 20 people involved in efforts to build a rigorous statewide teacher evaluation system over the past four years. Many did not want their names revealed because they are still involved in negotiations over teacher evaluation. Some spoke of frustration with a process they contend is fraught with politics, self-interest and mistrust, and in which what was best for children was seldom discussed.

Public hearings begin this morning in the House Education Committee on Senate Bill 103, Pavlov’s bill, which if passed would allow school districts across the state to continue to create their own evaluation tools, without any state-mandated standards.

If SB 103 passes the House and is signed into law by Gov. Rick Snyder, four years of negotiating for more robust teacher evaluation will end as it began: with no coherent system for assessing teachers’ strengths and weaknesses, and no way to ensure that struggling teachers are identified so that they can get the training and support they need to improve.

Why teacher evaluation matters

The fate of teacher evaluation legislation is critical for Michigan schools, which now rank in the bottom tier of public schools across the nation. It is widely acknowledged that no single factor inside schools has a bigger impact on student achievement than the quality of classroom teachers. For example, studies have shown that low-income students who are given access to a succession of highly effective teachers are able to close learning gaps with more affluent students. And yet Michigan schools have had no reliable system for determining which teachers are rock stars and which may be failing their students, year after year.

Before the Legislature first took a stab at improving teacher evaluation, some districts had not evaluated teachers for years. In others, evaluation often consisted of a principal spending a few minutes in each teacher’s classroom once a year, marking boxes on a checklist then delivering the results to the teacher.

The result: teachers were given little meaningful feedback on classroom performance, much less the tailored training and collaboration with colleagues that would help them boost classroom performance.

And across much of Michigan, nearly all teachers were being told they were doing just fine, even in schools where students were failing miserably.

That’s why in 2011, the Michigan Legislature, including Pavlov, worked closely with Gov. Snyder to reform the state’s teacher tenure laws, as well as evaluation, to hold teachers more accountable. Under the state’s tenure reform, schools were given more flexibility to pick and choose which teachers to lay off based on evaluations, rather than the number of years they’d taught.

But those reforms addressed only the broad outlines of how teacher evaluation should be carried out. For example, the 2011 legislation called for part of a teacher’s evaluation to be based on student growth during the school year, but left for later what kind of system would most reliably capture student improvement.

Other states had already started this journey, investing in sophisticated systems so that truly great teachers could be identified and rewarded for their work, while average or struggling teachers were given the tools to get better. Those teachers whose performance showed they just couldn’t cut it were eased out of the profession.

Creating such a system for Michigan was the mission of UM’s Ball, a national expert on teacher training, and her group. It was also the strong sentiment of Michigan residents.

Community conversations and polling conducted by The Center for Michigan found overwhelming support for increased teacher accountability, while also providing better support for educators.

As Bridge has reported, that’s what was happening in leading education reform states like Florida and Tennessee, whose students have lead the nation in academic improvement.

In Tennessee, schools choose from among evaluation models selected by the state. Districts can tweak those models to fit their needs, but the evaluations must be based on one of the four state-approved models.

“You really need rigorous guidelines and reporting,” said Sharon Roberts, Chief Operating Officer for SCORE, the State Collaborative On Reforming Education, an education reform organization in Tennessee. “What we learned loud and clear is you need a set of guidelines that are agreed upon … and rigorous reporting to ensure fidelity going forward.”

That would not happen under the Pavlov teacher evaluation bill now in Lansing. In his bill, local school districts would be allowed to retain virtually the same systems that as recently as 2012 still ranked 99 percent of teachers as effective or highly effective.

Sen. O’Brien co-sponsored the tougher teacher evaluation bill last year when she was in the House. She voted against Pavlov’s evaluation bill, as did four additional Republican colleagues of Pavlov’s in the Senate. His bill nonetheless passed the Senate 22-15 in May, and is now being considered in the House.

‘Local control’ or bust

Pavlov’s senate district covers the eastern shore of the Thumb, from St. Clair County on the south to Huron County on the north. He graduated from St. Clair High School, and took classes at St. Clair Community College without earning a degree. He ran a heavy truck sales and repair business before coming to Lansing.

Now 52, Pavlov said his motivation for removing state standards from teacher evaluation is simple: his bedrock belief in local control of education.

In an interview this week, Pavlov expressed doubts about the state Department of Education’s (MDE) ability to manage and enforce teacher evaluation standards.

“If you put the Department of Education in charge of this for all school districts, you are setting yourself up for failure,” Pavlov said. “The Department of Education is not equipped to handle teacher evaluation.”

He chafed at the suggestion that state “bureaucrats” should choose evaluation systems for public schools. Actually, the systems were chosen by Ball’s group, the Michigan Council on Educator Effectiveness, after being piloted in 13 Michigan school districts.

Though the council was created by the Legislature, Pavlov expressed concerns about the impartiality of the council, whose recommendations followed two years of study and cost more than $6 million.

“Any time you throw $6 million or $7 million at something, you have to be careful they’re not gunning for a (specific) outcome,” Pavlov told Bridge.

Instead of “micromanaging from the state,” Pavlov said, “we need to concentrate on giving schools flexibility.”

Among his concerns is the wisdom and cost of requiring training for observing teachers in class. “Why don’t we let them determine at the local level what works best for them?” he said. “They’re the ones doing the evaluation. It’s hard to say that the Department of Education knows more about it than the local superintendents at the end of the day.”

Superintendents may be closer to the needs of their districts than outside experts. But, as Ball has noted, most local districts don’t have the time, money or expertise to create reliable tools for the consistent observation and rating of classroom performance, let alone being able to accurately measure a teacher’s impact on student learning.

“Although the idea of developing a tool specific to a school district might be attractive to some administrators, the vast majority of school districts are not equipped to conduct the level of research necessary to demonstrate that their ‘home-grown’ tool is valid and reliable,” Ball wrote in April. “Without such assurance of validity and reliability, districts and the state leave themselves in legal peril.”

In an interview this week, Ball was more pointed in her criticism.

“Saying ‘local control’ doesn’t really make any sense,” she said. “Why would it matter if you’re in Grand Blanc or Petoskey how you would lead a class discussion that gets all the kids to take a turn? Why would it matter what district you’re in when you want to assure somebody can explain how to add fractions? Those things don’t have anything to do with local districts.

“Nobody would say that about any other profession. It would be a little bit like saying all the hospitals in the state should have different practices for surgery because they know best who their patients are. Do you want your pilot in Petoskey to land differently than they land in Detroit?”

The holdout

Sen. Pavlov’s differences are not only with Ball and her council. Late last year, the senator found himself facing off against a room full of fellow Republicans.

It was December, and advocates for tough evaluation reform thought their three-year fight was near completion. A tough, bipartisan bill had passed the House 95-14 and was sent to the Senate in the lame-duck session.

The bill had the backing of virtually every education group in the state, including support from the MEA (the state’s largest teacher union), and the conservative-leaning Great Lakes Education Project (or GLEP), which supports the state’s charter school industry. Noted a lobbyist familiar with the effort, “it had a coalition like I’d never seen before and don’t expect to see again.”

With Republican leaders of the House and Senate and the state’s Republican governor also backing the measure, rigorous teacher evaluation appeared days from passage.

“We had 27 votes lined up” in the Senate, with only 20 needed to pass the bill, said one lobbyist who supported the tougher measure. But they didn’t have the one vote ‒ that of Pavlov ‒ needed to bring the bill to a vote in Pavlov’s committee before it went to the full Senate.

It was a standoff. Pavlov versus everyone.

The senator found himself in heated negotiations with the bill sponsors (Rep. Adam Zemke, D-Ann Arbor, and then-Rep Margaret O’Brien, R-Portage), then-Senate Majority Leader Randy Richardville, R-Monroe, and Dick Posthumus, the state’s former lieutenant governor and now senior advisor to Gov. Snyder.

According to several people familiar with the negotiations, everyone in the room wanted the original, beefed up evaluation bill to pass, except Pavlov. At one point, there was a heated exchange between Posthumus and Pavlov, and Pavlov broke off negotiations.

“It’s very unusual, when you have a room full of powerful people who all want a resolution, for one person to scuttle it,” said one person familiar with the meeting.

Shifting support

Some education groups that supported a stronger evaluation bill last year, have now thrown their support behind Pavlov’s bill this year. Groups that have signed on include numerous intermediate school districts, including those overseeing schools in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties, as well as the Grand Rapids Public Schools, which ironically has a rigorous teacher evaluation model that is considered one of the best in the state.

Representatives from two groups acknowledged privately that their support for Pavlov’s watered-down bill wasn’t about which version would do most to improve student learning. They cited various other reasons:

Fear of state testing. If a teacher evaluation bill is not passed and signed into law this year by the governor, 50 percent of teacher evaluations will be based on student growth, as measured by tests. But standardized testing in Michigan is now in flux; last year, students took the MEAP; this spring, they are taking the M-STEP. The test may change again next year. In the bill sponsored by Pavlov, student growth on whatever statewide test MDE settles on will account for only 10 percent of a teacher’s evaluation in 2017-18, and 16 percent in following years, which many of these groups like.

Why should I pay for your evaluation system? Some districts developed extensive teacher evaluation models of their own, including some based on models recommended by Ball’s group. These districts don’t want the state monkeying around with their system. But they also don’t want to see the state hand over free evaluation systems to other districts when they had to pay for their own.

Fear of lawsuits. Some districts want to create their own evaluation systems without being forced to certify those systems are “valid and reliable.” So they support Pavlov’s bill, but are fighting a proposed amendment that would require them to certify their system is reliable. How would a district know, then, if its home-grown evaluation system was valid? “They wouldn’t,” said one lobbyist for a school group.

Other priorities. Some groups have other education issues that they care more about, such as allowing retired educators to work as substitute teachers and an expansion of how “sinking funds,” now used for repairs and construction, can be used. Those issues would remain on the back burner until the Legislature deals with teacher evaluation.

Exhaustion. “You can sense the fatigue on the issue,” said one person who has been involved in the issue for four years. “People are tired of talking about it. They want to move on.”

What the future holds

What changes will the current bill bring for Michigan students?

Not many, if it becomes law as written.

Pavlov’s bill “would not likely have a huge impact on student learning,” said Sarah Lenhoff, director of policy and research for Education Trust-Midwest, which helped write last year’s tougher evaluation bill and opposes the current version unless it is amended. “It allows so much flexibility that local districts could by and large do what they have been doing, which hasn’t produced variation in teacher ratings and hasn’t produced gains in student learning.”

Wendy Zdeb-Roper, executive director of the Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals, bemoans an opportunity lost if Pavlov’s legislation prevails.

“Schools that have a good evaluation system call it a game-changer,” she said. “The current bill will make no difference (because) there’s no criteria imposed on districts to make sure evaluation is rigorous and reliable.”

One education policy analyst expressed concern that leaving teacher evaluation in the hands of local districts will widen the gap between affluent and low-income districts.

Small and rural districts don’t have the resources to craft reliable evaluations, and there is little money to help implement such systems in their schools. “Maybe a district with 6,000 kids can muster some expertise, but what about smaller districts?” the policy analyst said. “We’re just telling people, ‘Best of luck, hope it works out for you, you’re all on your own.’

“The politics here and the right thing to do are not lining up well.”

Pavlov counters that his changes “don’t make it weaker, they make it workable. Less Lansing is better when it comes to teacher evaluation.”

Numerous people who spoke to Bridge hold out hope that the Pavlov bill will be strengthened by amendments in the House Education Committee, chaired by Rep. Amanda Price, R-Holland.

But the bill would then go back to the Senate for approval of changes. There, Pavlov could place more roadblocks to setting minimum state standards for teacher evaluation. And he seems prepared to do just that.

“Where we are right now,” Pavlov said, “is a split between what is a state role and what is a local role.”

That’s not how opponents of Pavlov’s bill say they see it.

“We came up with a fantastic product created by the best minds in education in Michigan that had a real chance of improving education in Michigan,” said one person involved in the debate. “We lost sight of that somewhere.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

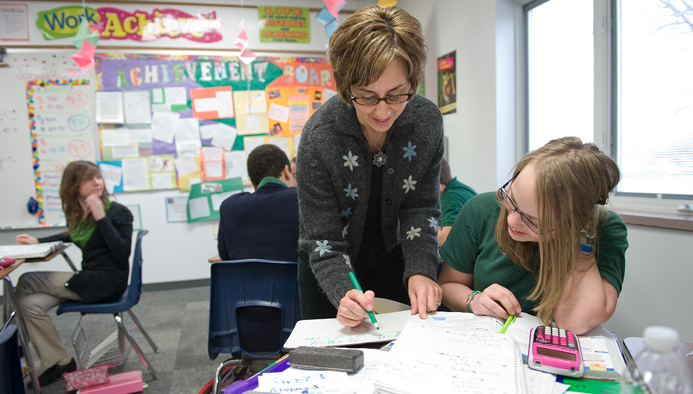

Many Michigan teachers won’t get research-based classroom observation and feedback as part of their annual evaluations if the current version of teacher evaluation legislation is passed and signed into law by Gov. Rick Snyder. (Bridge file photo)

Many Michigan teachers won’t get research-based classroom observation and feedback as part of their annual evaluations if the current version of teacher evaluation legislation is passed and signed into law by Gov. Rick Snyder. (Bridge file photo) Sen. Phil Pavlov, R-St. Clair Township, blocked rigorous state standards for teacher evaluation in favor of allowing local school districts continue to craft their own models.

Sen. Phil Pavlov, R-St. Clair Township, blocked rigorous state standards for teacher evaluation in favor of allowing local school districts continue to craft their own models.