New state teacher evaluation standards are no magic bullet

It took four years to build Michigan’s teacher evaluation policy.

And the real work is just beginning.

That work – which ranges from training school leaders to evaluate teachers, to creating local tests that measure how much a student learns from an individual teacher – will determine whether reforms turn around Michigan’s flailing schools, or if they’re just more state-mandated bureaucracy, according to educators who spoke to Bridge.

Signing a cutting-edge teacher evaluation system into law – which Gov. Rick Snyder is expected to sign Thursday – is an important step, but it’s only one step on a long road to turning around Michigan schools, cautions Amber Arellano, executive director of the Education Trust Midwest, a Michigan-based education reform organization that advocates for tougher, more consistent evaluation standards across the state. “This is probably the second step of 10 steps,” Arellano said.

Under the new policy, which you can read in its entirety here, Michigan’s approximately 100,000 public school teachers will receive evaluations that are based partially on student academic improvement, with 25 percent of the evaluation based on student test scores this year; student scores will rise to 40 percent of the evaluation beginning in 2018-19.

Half of the student score will come from M-STEP, the standardized test given to students across the state. The rest will come from tests chosen by individual school districts.

The student growth data will eventually include student scores over a three-year period, when there are three years of scores available under the relatively new M-Step.

Teachers will also be evaluated by at least two classroom observations during the school year by principals or others trained to observe classroom performance.

A mid-year progress report for new teachers and teachers on probation, and a year-end review for all teachers that includes goals for improving student achievement.

There are four ratings: highly effective, effective, partially effective and ineffective. Teachers who are rated ineffective three years in a row will lose their jobs.

School leaders and teachers will all receive training on the new evaluation system beginning next fall, in the 2016-17 school year.

“The most important element to a child’s education inside a school building is a teacher,” said Rep. Adam Zemke, D-Ann Arbor, one of the Legislature’s biggest advocates for teacher evaluation reform. “Teachers can’t be successful without good support.”

Why it matters

Teacher evaluation reform is critical to Michigan’s children. Once a top-10 education state, Michigan has seen its education rankings plummet compared with other states. In the just-released National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often referred to as the nation’s report card, Michigan students now rank 41st in fourth-grade reading, and are below the national average in math in fourth and eighth grade.

Studies show that students of all races and income levels can achieve significantly greater learning gains from having highly effective teachers in the classroom. Conversely, students taught by new or struggling teachers for multiple years are likely to lose ground to their grade-level peers, a problem that is particularly acute in low-income schools.

While studies support Zemke’s remarks on the importance of teachers, many Michigan districts had not meaningfully evaluated the effectiveness of their teachers before the legislature addressed evaluation reform in 2011. In other districts, evaluations consisted of a principal spending a few minutes in each teacher’s classrooms once a year, marking boxes on a checklist. Teachers were given little meaningful feedback or training on how to improve in the classroom.

And in too many Michigan schools, virtually all teachers were rated effective or highly effective, even as their students were underachieving. The problem with this approach was self evident: With all teachers rated highly, schools were not able to identify those teachers who were struggling and get them the training and support they needed to get better. At the same time, truly exemplary teachers were not getting the recognition and leadership opportunities they deserved.

“If you have 600 different evaluation systems (across the state), how do you ever know if you’re getting better?” said R.J. Webber, assistant superintendent for academics at Novi Community Schools. “How do you scale up training?”

In 2011, the Michigan Legislature, working with Snyder, passed teacher tenure and evaluation reforms. The evaluation bill provided only the general outlines for a new evaluation system; the details were to be worked out later.

“Later” ended up taking more than four years. A group of education experts pulled together by Snyder to fill in the details of a teacher evaluation system, led by renowned University of Michigan School of Education Dean Deborah Loewenberg Ball, turned in its recommendations to the legislature in the summer of 2013.

A bipartisan teacher evaluation bill that earned the support of groups as diverse as teacher unions and charter school organizations almost made it into law in December 2014, but was stopped by Senate Education Chair Phil Pavlov, R-St. Clair. Pavlov felt the bill gave too much control to the state Department of Education, and not enough leeway to local school districts to decide for themselves how to rate teachers.

Pavlov introduced his own version in the spring of 2015 that loosened statewide standards. That bill was in turn criticized for straying too far from the rigorous standards recommended by Ball’s commission. Negotiations continued over the summer, and a compromise bill was approved by both houses of the legislature in October. Snyder is expected to sign the bill Thursday.

“This feels like progress, I’m exciting about that,” Ball, the U-M education dean, told Bridge in her first public comments on the approved legislation. “The fact that we could get such broad agreement across party lines (the Senate approved the final version 35-2) … is very gratifying.”

Michigan’s new teacher evaluation system is “sooo much better than where we were,” Ball said. “This is an area that states are all having trouble with. It’s a step forward in a state that could exercise some real leadership. There are some things there that aren’t fully what we wanted but there’s training and the idea of standardized (evaluation) tools, and there’s reduction in the (reliance on) student achievement growth (compared with the 2011 legislation, which mandated 50 percent reliance on state test scores).

“I’m happy we were able to achieve a bill that moves us forward to the challenges of implementation.”

Now, the hard part

The impact in classrooms will vary among school districts. Many districts, knowing they would be required to toughen up their teacher evaluations, have already implemented more exacting policies. Many other districts are already using one of four teacher evaluation systems recommended by the state, or variations that closely resemble those systems.

As an assistant superintendent at Farmington Public Schools in 2012, Michele Harmala helped operate a pilot teacher evaluation program. When she was hired as superintendent at Wayne-Westland Community Schools, her new district already had its own evaluation program, too.

Both districts “took the view that we could wait until the state gets this sorted out, or we could move ahead,” Harmala said. Neither district saw any downside in improving their teacher evaluation system as soon as possible. “Teachers want to be good at what they do,” Harmala said.

The Michigan Education Association, the state’s largest teacher union, endorsed the reforms. “It represents a big step forward and a major improvement over the present haphazard process in evaluating teachers and administrators,” MEA president Steven Cook said.

Finally getting the governor’s signature on a bill provides certainty for teachers, principals and school districts. “It’s been such a political hot potato,” Harmala said. “Now we know it’s not going to change in a year and we can move forward. At a certain point, you have to start the work.”

That sentiment is echoed by Sen. Margaret O’Brien, R-Portage, who along with Zemke, the House Democrat, helped shape the tougher new standards.

“Now that we have an evaluation system that sets criteria for a quality evaluation system and student growth tools, we can focus on student learning,” O’Brien said.

“M-STEP (the state’s current standardized test, which replaced the MEAP last year) is new, and we have to look at recent data to understand how we can improve individual learning and growth. I look forward to working with the Department of Education to ensure that the tests not only measure (student) proficiency but actually measure growth of students.

“We must also disseminate the information to teachers so they can understand how to help each student,” O’Brien said. “Just having a score will not improve learning outcomes nor will it allow teachers to adapt to their students.”

State education leaders still have a lot of work in front of them. “Here we are building a system to hold teachers accountable and training evaluators on how to evaluate and MDE is developing a delivery plan, and all that work has to be done simultaneously,” said Education Trust Midwest’s Arellano.

So far, the state has set aside $14 million for classroom observation training. That may be just the beginning, Arellano said.

“There’s a lot of hard work and investment that still is going to be made,” Arellano said. “There are big opportunities, if we focus.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

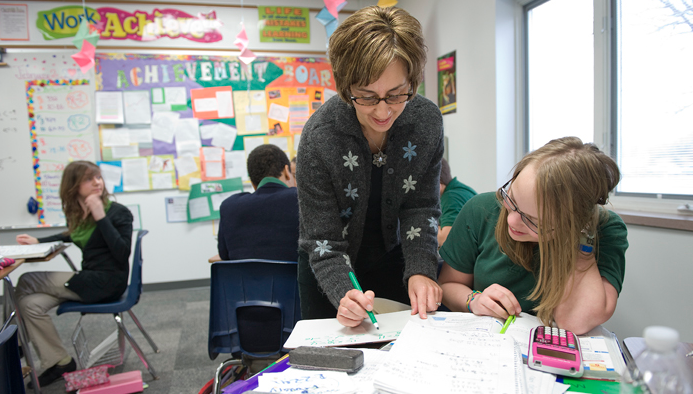

Michigan’s 100,000 public school teachers will get research-based classroom observation and feedback as part of a new teacher evaluation system. (Bridge file photo)

Michigan’s 100,000 public school teachers will get research-based classroom observation and feedback as part of a new teacher evaluation system. (Bridge file photo) Deborah Loewenberg Ball, dean of the University of Michigan School of Education, led a group of educators in designing the state’s more rigorous teacher evaluation system.

Deborah Loewenberg Ball, dean of the University of Michigan School of Education, led a group of educators in designing the state’s more rigorous teacher evaluation system.