Smartest kids: Ignoring outcry, Massachusetts leaders chose excellence

Editor’s note: This is the final installment of Bridge’s series, “The smartest kids in the nation,” chronicling how four high-performing or fast-improving states are making gains in education while Michigan remains muddled in mediocrity. We previously looked at the improving performance of students in Tennessee, Minnesota and Florida. Today we visit Massachusetts.

BOSTON‒In the spring of 1998, Massachusetts schoolchildren sat for a tough new test carrying the highest of stakes. Business leaders, educators and politicians ‒ Democrats and Republicans ‒ declared that the state’s economic future was riding on students’ performance.

And they failed miserably.

Three out of four 10th graders couldn’t pass math and six of 10 failed the English Language Arts section of the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System exam.

The backlash was immediate: The test was too hard. It demanded too much of immature minds. It robbed communities of local control. It was a plot to humiliate teachers’ unions. It would leave students of color behind.

What Massachusetts leaders did in response to this backlash would alter the state’s education legacy. These leaders not only kept the test, but made its passage a requirement for graduation.

Today, few would dispute that it has paid off.

Last year, 80 percent of 10th-graders passed the math and 91 percent passed the English Language Arts exam on their first try.

Massachusetts’ dominance in the classroom becomes more pronounced when its students are compared with their peers across the country on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Massachusetts has led the nation in all but one NAEP reading and math exam given since 2005.

Consider this: If Massachusetts were a country, it’s 8th graders would have placed second in the world the 2011 TIMSS science test, and fifth in math among 63 countries. Bay State reformers have begun boasting that they are not only building the smartest kids in America, but in the world.

Which is why Kati Haycock, president of the Education Trust, a Washington, D.C.-based research and advocacy nonprofit, urged Michigan to learn from Massachusetts when she spoke at the 2014 Mackinac Policy Conference in June.

Michigan students now score among the bottom tier of states nationally on the NAEP, making incremental gains while other states have improved dramatically. Last year, the average Michigan eighth-grader scored lower on the national math test than the average poor eighth-grader in Massachusetts.

Haycock noted that in the middle 1990s, Massachusetts students were “right in the middle of the pack” on national tests, just slightly better than Michigan. “But they got serious about it and now look at the difference. Year after year after year on the national tests, their kids lead the country.

“When people say, ‘No, our kids are too poor’ and, ‘We can’t do this,’ (Michigan leaders should) point to these successes and press for similar results.”

A 2014 study by Royal Oak-based Education Trust-Midwest, “Stalled to Soaring: Michigan’s path to educational recovery,” shows Michigan ranked in the bottom five states for student growth in fourth-grade reading and math over the last decade and was one of only six states where progress slowed, while other states are leapfrogging ahead.

In this series, Bridge visited four diverse states that are high-achieving or fast-improving to study their methods and see if they might make sense for Michigan: Tennessee and Florida where state policies have led to stunning growth; and Massachusetts and Minnesota, long acclaimed for their high-achieving students.

Staying the course

The architects of the Massachusetts system point to a nearly two-decade commitment to a high school exit exam based on a rigorous curriculum. But that is only one factor in its success. Massachusetts uses a different school funding formula than Michigan, has insisted on quality standards for its charter schools, while improving teacher preparation and preschool programs.

If two decades of reform have yielded a lesson, it is this: When kids get what they need to learn, they learn.

This is what Massachusetts did:

- Made its school more academically challenging by designing a rigorous, statewide curriculum and a single exam that every student must pass to graduate from high school. Despite already high standards, Massachusetts became one of the first states to adopt the Common Core State Standards in 2009.

- Changed the state’s school funding tax system to invest more in schools in low-income areas. The formula takes into account cost-of-living variances and a community’s ability to fund schools.

- Developed a statewide annual teacher and administrator evaluation process; made teacher certification more difficult, and moved to hold colleges with teacher preparation programs more accountable for their graduates’ performance in the classroom.

- Struck what was called a “grand bargain” (link to charter school sidebar) that allowed charter schools in the state, but required them to work under strict guidelines to ensure high quality.

Forged a long-term commitment to academic rigor among politicians, schools and the business community

The state’s commitment to a rigorous education for all is on display at two Boston schools filled with students from low-income neighborhoods.

In September, Bridge visited Match Charter High and Orchard Gardens K-8 Pilot School to learn why their students are scoring higher or improving faster than many students from affluent suburban communities. The answer, it seems, lays in the school’s determination to keeping pushing its ambitions higher.

“It’s an easy trap to fall into to say ‘Orchard Gardens is successful, we did it. We’ve produced a lot of growth,’ said Megan Webb, its 34-year-old, Harvard-educated principal. “Now we have to do the really, really hard work of pushing uphill from a higher plane.”

A deer in headlights

In fairness, Massachusetts was better positioned to improve its academic standing than most states. It has, for instance, a more educated population, leading the nation in the percentage of adults with an associate degree or higher - 50.5 percent, compared with a national rate of 39 percent and 37.4 percent in Michigan. And Massachusetts enjoys the nation’s third highest average personal income of $56,923, compared with $39,215 in Michigan, which is 35th.

But until the state began the hard work of reforming its education system, Massachusetts’ K-12 schools didn’t reflect those advantages. The state used to be, as Kati Haycock put it, middling ‒ not much different from Michigan in student achievement and education spending.

In 1992, Michigan’s eighth graders scored at the national average scale score of 267 in math on the NAEP, with 19 percent considered proficient. In Massachusetts that year, eighth graders scored 273 on math, with 23 percent meeting proficiency standards.

That’s as close as Michigan would come.

Dissatisfied with the scores, Massachusetts business leaders concluded that its students weren’t scoring well enough for the state to be globally competitive down the road. Nobody wants their company located in a state where kids aren’t trained to be thinkers.

It was a deer-in-headlights moment, said Paul Reville, one of the Founding Fathers of the Massachusetts school reform. Massachusetts passed the Education Reform Act of 1993 (MERA), which ramped up the requirements for what students were expected to learn, called for more education funding and legalized charter schools. Tough, statewide standards were created in English language arts, foreign languages, health, mathematics, history/social science, and science, technology and engineering.

State education leaders sought input from more than 50,000 residents in developing the standards, known as the Massachusetts Common Core of Learning, which outlines what all students are expected to know and be able to do by the time they graduate from high school.

Reville, a former Massachusetts secretary of education, said the real difference-maker was the creation of a high school exit exam.

“The first couple of years it didn’t count (towards graduation), or we would’ve been failing huge numbers of kids,” said Reville, now a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. “Sure enough, when it counted, magically the scores jumped, so obviously it was an effort factor.”

At first, failure

The first MCAS test in math and English was given to students in fourth, eighth and 10th grades in 1998. Much like the Common Core standards that are being implemented across Michigan and many other states today, the Massachusetts test was based on the tougher standards and placed a greater emphasis on critical-thinking and problem-solving skills.

Last year, more than a half-million Massachusetts public school students in grades 3–10 took the tests in English Language Arts, math, science, and technology/engineering, state education officials reported.

“(T)he MCAS is doing what it is supposed to be doing. It is testing students on what they need to know and the skills they should have in order to function in the world after they graduate from high school,” concluded a 2005 study by the University of Massachusetts Center for Educational Assessment and Measured Progress.

In 2009, state education leaders sought to raise standards even more when Massachusetts was one of the first states to sign onto the Common Core State Standards Initiative, standards that have drawn blowback in some states, including Michigan, for what critics contend is an effort to weaken local control over education. All Massachusetts schools implemented Common Core by 2011.

So what’s happened to the six-point gap that separated Michigan and Massachusetts in eighth-grade math in 1992? It has widened fivefold.

In 2013, Massachusetts eighth graders had an average scale score of 313 on the math NAEP test, while their Michigan peers stood at 280, 33 scale points behind. Michigan’s average eighth grader had a math scale score one point lower than Massachusetts’ average poor eighth grader.

While Massachusetts is leaving most every state behind, state leaders say it’s not yet time to cue the parade. There are still wide achievement gaps between poor and higher income students, and between students of color and white students, according to the Rennie Center for Education Research and Policy, co-founded by Reville.

By the third grade, poor children in Massachusetts, as elsewhere, are already far behind. Last year, 57 percent of all students passed Massachusetts’ third-grade English test, while 35 percent of low-income students passed; in math, 55 percent of all third-graders passed, compared with 32 percent of poor students.

Still, student populations that typically struggle are outperforming their demographic peers in Michigan and across the nation.

All means all

Orchard Gardens K-8 Pilot School is a fairly new building, about 11 years old, and surrounded by community centers, a public park, and housing projects just up the street from a hospital complex. The day before school started in September, the sidewalk across the street was pocked with ripped lottery tickets, tiny liquor bottles and pages from a porn magazine.

Orchard Gardens used to be one of the worst schools in Massachusetts. It was known among teachers as a career killer - the kind of poor school with poor test scores that would end any educator’s chance to move up and on. About 73 percent of the children are from low-income homes. More than half of the 860 students are bilingual, many from families that immigrated from Cape Verde, a chain of islands off the coast of Africa.

Today, Orchard Gardens is held up as a star performer; an example of the state reformers’ mantra of “all means all” – that is, that all students, no matter their circumstances, can learn at high levels.

How high?

Orchard Gardens students have been invited to the White House. Three times. Their scores are still below the state average but the trajectory of their growth shows learning is taking place at record speed. The school’s improvement rate was in the top 2 percent in the state in 2012.

The school’s leaders cite the autonomy they’ve been given by the district to make changes, along with partnerships that have given the school resources that it could not have provided to teachers and students on its own. Orchard Gardens was designated as a turnaround school in 2010, which meant it had three years to improve or face a state takeover. To aid the turnaround, the school was given a share of the $250 million in Race to the Top grants the state won from the federal government.

Meanwhile, Boston Public Schools made Orchard Gardens a pilot school, giving its leaders more authority over its budget and hiring. The principal at the time fired about 80 percent of the teachers, even though turnaround status only required removing 50 percent. Security officers were let go to make room for arts teachers. The school day was extended by an hour, and after-school programs kept some students there until 5:15 p.m.

An emphasis was placed on improved reading skills for younger students. Every teacher through the second grade has a trained assistant to run small reading groups. The help comes from one of a dozen community organizations that also help provide after-school tutoring.

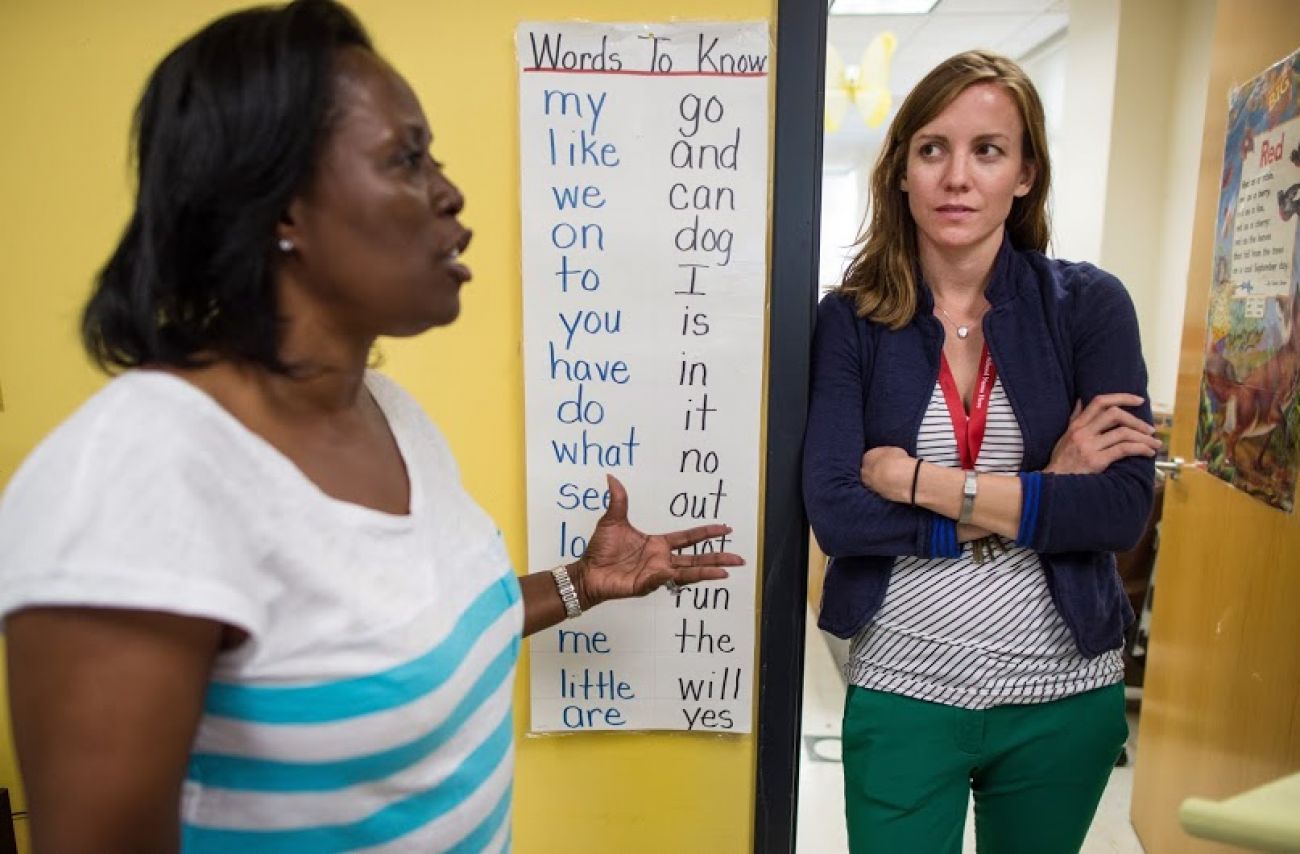

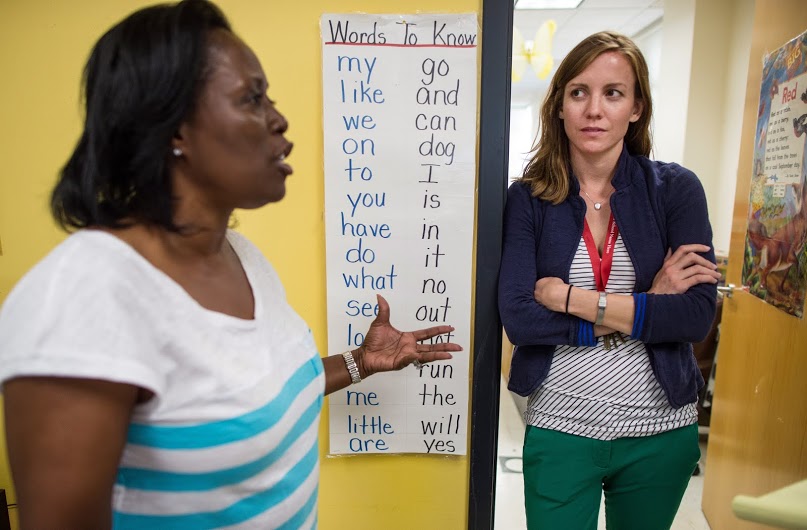

First-grade teacher Darlene White-Dottin, whose class recited Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a Dream” speech for President Obama, was recruited to Orchard Gardens after the mass firing. She said focused reform gave the school the autonomy it needed to hire the right staff.

“Here we have resources and input,” the 30-year teaching veteran said. “When I started teaching, it wasn’t like that.”

More poverty, more money

In 1969-70, Massachusetts and Michigan spent the same amount of money on education - about $4,547 per student. By 2013-14, Massachusetts spent $13.9 billion on schools compared with $11.5 billion in Michigan – that’s $2.4 billion more even though Massachusetts has 600,000 fewer students.

“The core of reforming the financial system was recognizing if you rely on low-income communities’ resources alone to fund schools in those communities and wealthy districts to fund their schools you will always have lower-funded schools in low-income districts. In the long term, that was a recipe for disaster,” said Noah Berger, of the Massachusetts Center for Budget and Policy, an independent nonprofit that provides nonpartisan research and analysis of state budget and tax policies.

“A strong economy needs well-educated workers and you need to make sure all of your people have a chance.”

The decision to spend more money in poor communities was spurred largely through the courts. Students from property-poor districts won big in a 1993 case in which students argued that the state wasn’t meeting its constitutional duty to adequately educate students in poor neighborhoods. Within days, the a Democratic legislature passed the Massachusetts Education Reform Act, a measure signed by Republican Gov. William Weld. The act included a complex formula to cure funding inequities, phased in over seven years.

The state set a minimum funding threshold for each school district, based on such factors as teacher salaries, and the tax base and cost of living in each community. The formula allows high-need districts to receive extra support for services to poor, bilingual and special education students.

Massachusetts has also provided more state funding for preschool programs. Between 1996 and 1999, Massachusetts increased spending on early childhood education by 247 percent, according to a study by University of Massachusetts Amherst School of Education.

Bye, partisanship

Education reform in Massachusetts was never an entirely altruistic effort. It gained momentum with powerful institutions in the state because it was economically the right thing to do. In a global economy, knowledge is power.

The business community concluded that Massachusetts’ place in that economy depended on improving student performance, similar to the way Japan and Poland responded after the devastation of World War II.

The Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education led the charge for reform in 1993 with its report, Every Child A Winner! The group, representing the largest statewide business organizations, was so integral to reform it was appointed to state committees on teacher evaluations, curriculum and budget review.

“We did a poll with two other groups and found 69 percent of employers were having trouble filling jobs due to a skills gap,” said Linda Noonan, executive director of the Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education. “We can’t have a disconnect between what the business community requires and what kids can do.”

In a heavily Democratic state, one Republican governor after the next, including Michigan-born Mitt Romney, followed the business group’s lead.

As a result of the collaboration among business, politicians and education leaders, Massachusetts has become the darling of American school reform.

Whether Michigan could follow Massachusetts’ lead depends on whether Michigan’s fractious Legislature can hash out a plan and stick to it, according to Reville.

“What worries me about what I read is going on in Michigan is that (education reform) strategies have become tools of political battle rather than instruments for improvement,” Reville said.

Education reform does not have to be a Kumbaya, let’s-all-get-along affair. Ultimately, it’s all about doing what’s necessary to boost the state’s economic future, money, he said.

“Why else are people going to come to Michigan? They’re going to come because you have people who can do the jobs of the future. School systems are the main instrument for getting that accomplished.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Paul Reville, a former Massachusetts secretary of education, was one of the driving forces behind the state’s education reform. He said implementing a tough high school exit exam helped teachers and students focus on higher achievement. (photo credit: Aram Boghosian)

Paul Reville, a former Massachusetts secretary of education, was one of the driving forces behind the state’s education reform. He said implementing a tough high school exit exam helped teachers and students focus on higher achievement. (photo credit: Aram Boghosian) First-grade teacher Darlene White-Dottin, left, with Principal Megan Webb, had her class invited to the White House. She was brought in after most of the staff at Orchard Gardens K-8 Pilot School was fired as part of a successful reform turnaround effort. (photo credit: Aram Boghosian)

First-grade teacher Darlene White-Dottin, left, with Principal Megan Webb, had her class invited to the White House. She was brought in after most of the staff at Orchard Gardens K-8 Pilot School was fired as part of a successful reform turnaround effort. (photo credit: Aram Boghosian)