Three years later, jury still out on Michigan’s cyber school expansion

From his Lansing office, Gov. Rick Snyder read aloud a book about a goldfish and its fishbowl neighbors. As he finished each page, he turned the book around to face his computer screen and smiled.

In homes across the state, 90 children enrolled in the Michigan Virtual Charter Academy were watching him from their computer screens.Education advocates, meanwhile, were watching in their own way, waiting to see what happened next.

It was March 2013, and a law allowing for the expansion of cyber charter schools – schools in which students study full-time at computers in their homes rather than in traditional classrooms – had just gone into effect.

“Our goal is student growth,” Snyder told media that day, “and we want to create whatever venue works best for them.”

Two and a half years later, it’s still unclear how well the expansion has worked.

Online charter enrollment has more than quadrupled since the law went into effect, demonstrating the allure of cyber schools for some Michigan students. But if improving student achievement was Snyder’s goal, many online charters are failing families of students in grades one through eight.

A Bridge Magazine analysis of student test score data reveals that most online charters in Michigan are under-performing in elementary and middle school compared with schools whose students come from similar economic backgrounds. Among four online charter schools offering elementary and middle school grade classes in Michigan, only one reached the state average for student test scores among economically similar schools.

More coverage: In one tech-heavy cyber school, a low-tech strategy spurs learning

High school is a different story: the four online charters that enroll high school students all exceeded state averages, with one scoring in the top 5 percent of all high schools.

The scores are based on Bridge’s 2014 Academic State Champs ranking system, which compares student test scores of schools with test scores at economically similar schools. Bridge determines economic similarity by comparing the percentage of students who qualify for free or reduced- price lunch.

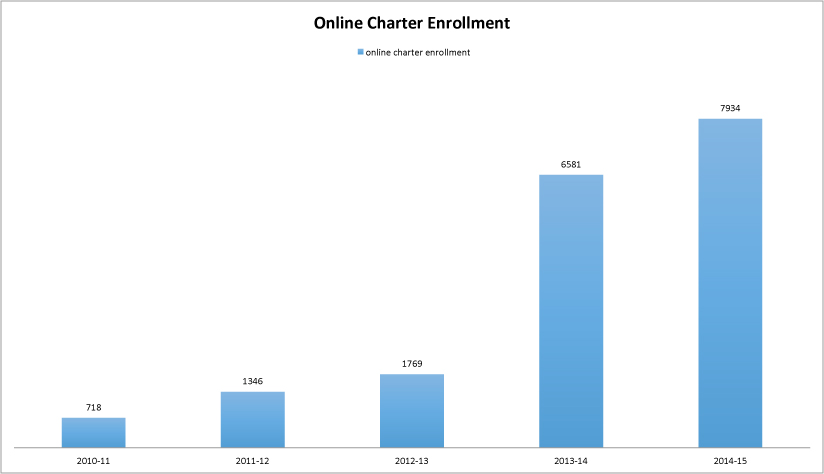

Enrollment in cyber schools exploded after the new law went into effect. Online charters grew from two (allowed as part of a pilot program) in 2012-13, to 10 last year, with total enrollment growing from 1,769 to 7,934, according to data kept by the state.

There’s potential for more growth; only 10 cyber charters were allowed to operate last year. Beginning this school year, the law allows up to 15 online charters. The law also allows a maximum of 2 percent of public K-12 students to be enrolled in cyber charters. That’s about 30,000 students.

Enrollment in Michigan’s virtual charter schools has more than quadrupled since the enrollment cap was raised. The roughly 8,000 students now enrolled full-time in online charter schools remains well under the 31,000 students that the law permits to be enrolled under the new cap.

Enrollment in Michigan’s virtual charter schools has more than quadrupled since the enrollment cap was raised. The roughly 8,000 students now enrolled full-time in online charter schools remains well under the 31,000 students that the law permits to be enrolled under the new cap.

Source: Michigan Department of Education and www.mischooldata.org

Currently, about one-in-250 Michigan students is enrolled full-time at a cyber charter school, taking all of their classes online.

While cyber schools are attracting students, children in grades 1-8 aren’t doing as well academically as their peers in traditional brick-and-mortar buildings.

In Bridge’s 2014 Academic State Champs ranking, a score of 100 indicates a school’s students are performing at par with students in schools with a similar percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Only Michigan Connections Academy, based in Okemos, met that standard in elementary or middle school

Icademy Global, based in Zeeland, had the lowest scores for both elementary and middle school. Its elementary school score of 82.35 for 2013-14 ranks it in the bottom 2 percent of all elementaries in the state.

Enrollment and enrollment growth appear to bear no connection to test scores. For example, elementary students at the Michigan Great Lakes Virtual Academy, based in Manistee, had test scores that ranked the school in the bottom 20 percent of all elementaries in the state in 2013-14. Yet enrollment ballooned from 474 that year, to 2,008 the next year.

Michigan Virtual Charter Academy, based in Grand Rapids, had the largest enrollment among Michigan’s cyber charters in 2014-15, with 2,804 students. Its elementary school student test scores ranked in the bottom 30th percentile.

Michigan Connections’ elementary students, by contrast, ranked in the 53rd percentile.

Cyber charter high school students perform better, with all four schools that enrolled high school students ranking in the top half of high schools in the state. Michigan Connections’ high school led the way with a ranking in the top 5 percent.

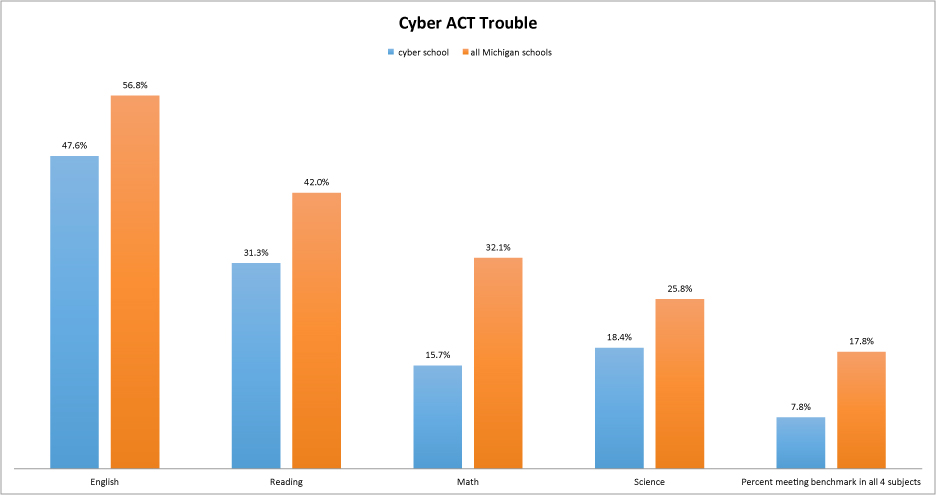

Yet even at the high school level, there are reasons for concern. The ACT scores of juniors enrolled full-time in cyber charters were significantly lower than the scores of juniors statewide. Under 8 percent of cyber juniors earned scores that deemed them college and career ready in all subject areas, compared with about 18 percent statewide, in 2013-14.

High school juniors enrolled full-time in online charter schools fared significantly worse on the ACT than juniors on average across the state.

High school juniors enrolled full-time in online charter schools fared significantly worse on the ACT than juniors on average across the state.

SOURCE: Michigan Virtual University

While the academic data for Michigan cyber charters could be considered mixed, there’s less uncertainty nationally. The academic performance of students in full-time virtual schools across the U.S. is “utterly and unexplainably terrible,” said Gary Miron, an education professor at Western Michigan University and a national expert on cyber schools.

“And that’s for the schools we have data,” said Miron, one of the authors of an annual report on the performance of virtual schools published by the National Education Policy Center. “A high proportion don’t have data,” because they’re new or because they have too few students per grade to be counted in state-level data.

Nonetheless, Miron is an advocate of online learning, teaching an online course. But he says he is concerned about accountability in full-time virtual charter schools nationally, a field that is dominated by for-profit companies.

“Basically, they’re doing what you’re supposed to do as for-profit company: reducing cost and lobbying to increase prices for the products,” Miron said. “It’s an unregulated field.”

In Michigan, at least 94 percent of cyber charter students were enrolled last year in schools operated by one of the two largest national cyber school providers, K-12 Inc.

Cyber academies receive the same per-pupil foundation grant as other brick-and-mortar public schools in Michigan, roughly $7,200, even though virtual schools do not have the building and maintenance costs of traditional schools.

“The money we don’t have to pay for a new boiler, we invest in curriculum,” said Bryan Klochack, principal for Michigan Connections Academy, and former principal at Marshall High School.

Online charters also spend more money on marketing than traditional schools to attract students. A 2012 USA Today report found that cyber school providers were purchasing ads on Nickelodeon and The Cartoon Network.

How much companies spend on marketing wouldn’t be an issue if the schools were performing well academically, said John Austin, president of the Michigan State Board of Education, who opposed the 2012 expansion of cyber schools.

Among students enrolled in full-time cyber schools in Michigan, 44 percent of classes ended in either a failure or a withdrawal without credit, according to an analysis by Michigan Virtual University, a private, nonprofit set up by the state in 1998 to offer online courses to Michigan students.

Austin draws a distinction between online courses that are a graduation requirement in Michigan high schools and full-time cyber charter schools. About 320,000 students in the state took some kind of online course last year, most as a supplement to their traditional classwork.

Expanding the cap on cyber charters before knowing how well the two operating cyber charters were performing was “a huge mistake.” Austin said. “For a lot of kids, online-only learning is not helping.”

Karen McPhee, senior education advisor to Gov. Snyder, did not return an email request for comment. Dan Quisenberry, president of the Michigan Association of Public School Academies, an organization that advocated for cyber school expansion in 2012, also did not return requests for comment.

Lessons for traditional schools

Andrei Nichols, interim head of school at Michigan Virtual Charter Academy, said critics are asking the wrong questions. Instead of focusing on how much money cyber charters spend on marketing, education leaders should ask why so many students want to leave their traditional school building.

“If a family is in a position where they can go to their local brick and mortar school and it meets their needs, by all means do it,” Nichols said. “But there are families … who traditional schools are failing who want another option.”

Online schools aren’t a good fit for a lot of families. The families whose children succeed in online schools are families who are involved in their student’s learning, Nichols said. Teachers at his cyber school spend a lot of time on the telephone with parents, discussing how the students are doing.

“The virtual world would not work without family involvement. Let’s be frank, you can’t leave an 11-year-old at the table and expect them to do their work,” Nichols said. “The virtual world (sees) the challenges of the brick and mortar world: attendance and kids coming in below grade level. That’s why we need all the interventions we have.”

That, Nichols said, may be a lesson that traditional schools could learn from cyber schools, where teachers and administrators must have a high level of contact with students and parents if the students are going to succeed.

“When parents are involved in the learning process, good things do happen.” Nichols said. “If you were to take that parental involvement in the virtual world and recreate it in brick and mortar schools, we could be put out of business.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Online schooling allows children in Ironwood in the Upper Peninsula to take classes from a school based in Okemos. From left to right, fifth-grader Gabbi Maki, first-grader Brynn Maki, and third-grader Keaton Maki, are enrolled in Michigan Connections Academy. (courtesy photo)

Online schooling allows children in Ironwood in the Upper Peninsula to take classes from a school based in Okemos. From left to right, fifth-grader Gabbi Maki, first-grader Brynn Maki, and third-grader Keaton Maki, are enrolled in Michigan Connections Academy. (courtesy photo)