Snyder has steadied state finances, yet that may not be enough

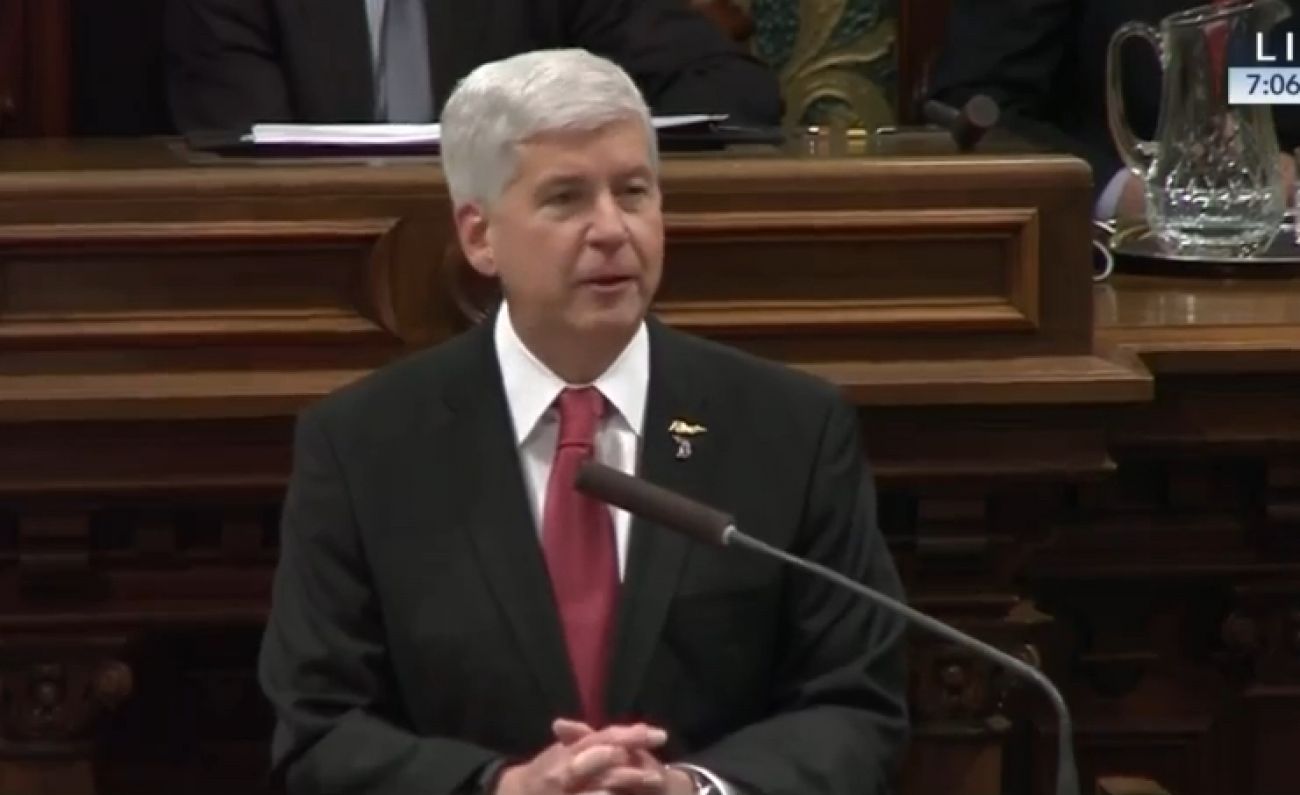

Gov. Rick Snyder came to Lansing nearly seven years ago with a plan to improve fiscal management within state government.

And his reforms have left Michigan in better shape than most states when it comes to preparing for the next recession, according to one national fiscal researcher.

Yet despite having a CPA at the wheel, Michigan faces budget pressure down the road that is expected to squeeze its general fund in the next few years, even as the state’s economy is still expected to grow. Some experts say Michigan still lacks enough reserve money for tougher times. And Michigan still lags leading states in the percentage of its residents with college degrees, an indicator of a robust economy.

MORE COVERAGE:

Is Michigan ready for the next recession?

One thing working to Michigan’s advantage is that the state has done a better job setting aside money in reserves, said Dan White, director of fiscal policy research for West Chester, Pa.-based Moody’s Analytics. The firm recently put all 50 states through stress testing to determine whether they have saved enough money for lean times.

The state’s rainy-day fund has a balance equal to about 9.8 percent of general fund revenue for the 2017 fiscal year, according to Moody’s, with 10 percent being the benchmark. The average state has saved between 5 percent to 6 percent in reserves, White said.

But having a healthier balance doesn’t mean Michigan is entirely recession-ready, he said. Moody’s actually recommends Michigan have 13.9 percent of its general fund revenue in reserves to withstand a moderate recession without disruption. The higher level is based in part on the relative volatility of the state’s tax revenue.

In a downturn, having money for a rainy day will be important because the general fund primarily consists of revenue from the state’s 4.25 percent income tax. Income tax revenue is the most sensitive to a recession because it’s directly tied to employment, said Craig Thiel, research director for the nonpartisan Citizens Research Council of Michigan. If fewer people are working, less money comes in.

Economists forecast slower state revenue growth in the next few years. A recession also could put more pressure on the state’s Medicaid spending if residents’ income drops, according to the research council. Universities and public schools also could be targeted for budget cuts.

Vulnerable as well: state money for cities and townships, known as revenue sharing. The state’s share of statutory revenue sharing to cities, townships and villages — paid for with sales tax revenue — remains below where it was a decade ago. That is a problem for local governments because state law limits how fast property values can rise, meaning local governments lose more revenue from property taxes during a downturn than it can recover in a good year.

Combine that with Lansing’s decision to divert $600 million from the general fund for road repairs by 2021 and phase out a personal property tax on manufacturing equipment, and “the state is going to be not in a great position to help local units of government should a downturn come,” Thiel told Bridge.

Unemployment falls in Michigan

Michigan’s unemployment rate has steadily fallen since peaking at 13.7 percent in 2009, the height of the Great Recession.

- 2000: 3.6%

- 2001: 5.2%

- 2002: 6.3%

- 2003: 7.2%

- 2004: 7%

- 2005: 6.8%

- 2006: 7%

- 2007: 7%

- 2008: 8%

- 2009: 13.7%

- 2010: 12.6%

- 2011: 10.4%

- 2012: 9.1%

- 2013: 8.8%

- 2014: 7.3%

- 2015: 5.4%

- 2016: 4.9%

State Treasurer Nick Khouri, a Snyder appointee, said he wants state and local leaders to address the municipal revenue problem — along with ballooning retirement benefits and the efficiency of local services — while the economy is still strong.

“During the next recession, many local units of government are going to have severe fiscal stress, and what I’ve argued is that we ought to address those issues now while we have some wind at our back, instead of doing it in a crisis,” Khouri said. “The worst way to solve public policy problems is during a crisis.”

The Snyder administration took office in 2011, shortly after the economic crisis that officially lasted from late 2007 to June 2009.

Snyder has put in place fiscal and tax reforms, including replacing the Michigan Business Tax with a flat 6 percent corporate income tax and ending a number of business tax credits. (This year, he would sign into law a few new incentives.)

Snyder also pushed the GOP-majority Legislature to adopt budgets earlier, in June, to bring more certainty for aid to local governments that start their fiscal years in July, and to avoid impasses with lawmakers that contributed to government shutdowns in 2007 and 2009 under Democratic Gov. Jennifer Granholm.

And Snyder has taken steps to address unfunded pension and health care costs for government retirees and set nearly $900 million aside in Michigan’s rainy-day fund through 2018.

Snyder lowered assumptions about the rate of return on investments in state pension systems, and in July signed legislation to steer new teachers toward 401k-style retirement savings accounts, rather than traditional pensions. He also convened a task force to look for ways to tackle billions of dollars in local government debt accrued from underfunded pensions and retiree health care benefits.

Yet the extent to which elected officials in any state deserve credit or blame for economic growth or decline is open to debate, said Jeff Guilfoyle, an economist and a vice president at Lansing-based Public Sector Consultants, who worked in the state Treasury Department during the Engler and Granholm administrations.

Much of the economic growth Michigan has experienced over the past eight years has been the result of an improving and cyclical national economy, Guilfoyle said. The state also benefited from Washington’s decision under the Bush and Obama administrations to intervene with a controversial financial rescue when Detroit automakers were about to collapse.

“Had they not saved (General Motors) and Chrysler — I mean, people forget because it’s been a few years — the world would have come to an end here,” Guilfoyle said.

The state had slightly more than $2 million in its reserves from 2005 to 2011, Treasury data show. At about the same time, the state was borrowing cash just to pay its bills. The last time that happened was in the 2011 fiscal year, the state said.

Aside from the rainy-day fund, the state will have roughly $5.8 billion in what’s known as common cash by year’s end, according to Treasury. Khouri said the state budget now avoids using one-time money to pay for ongoing programs, which can create a funding crunch later when the money disappears.

“We’ve built up a reserve in case there’s a liquidity crunch,” he said.

And yet, that might not be enough, said Robert Kleine, a former state treasurer under Granholm and a principal of Great Lakes Economic Consulting, a firm he started with former Michigan House Fiscal Agency Director Mitch Bean.

He noted that the state had $1.2 billion in its rainy-day fund in 2000, but the relatively mild 2001 downturn quickly churned through it. Treasury data show the state’s reserves tumbled to just $145.1 million by 2002.

“Probably, $1 billion is not enough given an average recession,” he said. “That may be the only amount that’s realistic, but I don’t think it’s necessarily enough.”

Kleine said the state has also created tight budget conditions by diverting general fund dollars to roads, business tax cuts and credits and reimbursements to municipalities after phasing out the state’s personal property tax on industrial equipment.

“I don’t think (the state’s budget is) that well-prepared, given all the money that’s been allocated for other purposes and given the spending needs that we have in the state,” he said. “I know Nick would disagree with me.”

Michigan has other problems that bring acute challenges to ordinary residents during a recession. It is now considered a low-education, low-skill state, said Charles Ballard, a Michigan State University economist, so people with fewer skills who were hurt the most during the last recession are disproportionately likely to be harmed in the next one.

Michigan has reduced support for public welfare programs, including lowering how many weeks a person can receive unemployment benefits; imposing lifetime caps on the amount of cash assistance a person can receive, and using household assets, rather than solely income, to determine food assistance benefits, said Gilda Jacobs, president and CEO of the Michigan League for Public Policy, a nonpartisan think tank that advocates for vulnerable residents.

Factory workers will continue to be vulnerable as manufacturers boost automation, Jacobs said. Less discretionary income during a downturn also will hit the retail and service sectors.

“We’ve been talking about this for a long time,” she said. “We need to have a benefit program that is adaptable to things. We don’t work in a black-and-white world.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!