Nest eggs go bad in Oakland County

When Sven Gustafson and his wife Kristen bought a home in the Oakland County community of Ferndale in 2005, it looked like a smart move.

Property values had been rising steadily. Ferndale, which borders Detroit along Eight Mile Road, was becoming a haven for young professionals, artists and gay Michiganians -- the “creative class” described by futurist Richard Florida.

But then came the Great Recession in 2007. Since then, Ferndale has seen its state equalized residential property values fall 36 percent. The Gustafsons experienced an even larger drop in the value of their home.

With a growing family and money becoming tighter, they asked their bank last year to refinance their mortgage at a lower interest rate.

But after the house was appraised at half of what the Gustafsons had paid for it five years earlier, the bank said no.

But after the house was appraised at half of what the Gustafsons had paid for it five years earlier, the bank said no.

“It was a real punch to the gut,” said Sven Gustafson, who works as a communications writer for a large health insurance company.

Gustafson said his mortgage is underwater “big time,” meaning he owes more on his mortgage than his house is worth. He said it seems fruitless to keep making the monthly payments when he might never catch up.

“It could be years before we recover the value of our home,” he said. “I’m not sure we can hang on that long.”

The Gustafsons are far from alone. Statewide, 36 percent of all homeowners with mortgages owed more than their homes were worth at the end of June, according to CoreLogic, a California-based financial data company.

Economists say virtually all the impacts from being underwater are negative. Underwater homeowners looking for better employment opportunities in another locale are likely to have a hard time selling their homes.

And many are cash poor from job losses, pay cuts and paying a mortgage that has become increasingly difficult to afford.

Lower property taxes from declining property values probably haven’t helped homeowners or the economy much, said University of Michigan economist Don Grimes.

Most homeowners are likely saving the money or using it to make mortgage payments.

“Nobody is spending it,” Grimes said. “To the extent they’re spending it, they’re spending it on necessities.”

But some have been able to keep from drowning in mortgage debt.

Dave Hilbert, who works at Ford Motor Co. as a skilled trades coordinator, was able to refinance the mortgage on his Lake Orion home through the Obama administration’s Home Affordable Refinance Program.

Many have not been able to qualify for the refinancing program because of numerous restrictions. But Hilbert did and was able to reduce his interest rate from 6 percent to 3.375 percent.

He said he refinanced in order to knock a few years off his 30-year mortgage as he and his wife near retirement.

“We are cutting our mortgage by seven years and are only paying a little over $100 a month more,” Hilbert stated in an email.

Grimes said property values in Michigan won’t start to rise again until home prices begin to stabilize.

Some say that appears to be happening, particularly in hard-hit Southeast Michigan. But home prices will likely be under pressure for years because of the large number of foreclosed homes banks are selling a fire sale prices.

About a third of all home sales this year in Oakland Country were foreclosed homes, said Robert Daddow, deputy county executive.

And with more than 13,000 new foreclosure filings in Michigan so far this year, Daddow said he doesn’t see an end to the foreclosure sale problem anytime soon.

That’s a discouraging prospect for Gustafson and others like him.

“You feel like you’re just giving money to the bank when you make your mortgage payment,” he said. “You’re not building any equity at all.”

When times were good in Michigan, they were very good in Oakland County.

Home to many of the state’s captains of industry, Oakland County prides itself on having top-notch public and private schools, attractive downtowns and the wealthiest citizens in Michigan.

In the booming 1990s and early 2000s, County Executive L. Brooks Patterson regularly bragged that Oakland County was among the top five richest large counties in the nation.

But the county has fallen hard in recent years, a result of the implosion of the auto industry and a booming real estate market that went bust.

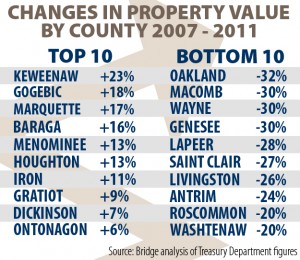

Over the past four years, it has led the state in a statistic that county officials aren’t boasting about: its stunning loss of property value.

Since 2007, Oakland County has lost $25 billion in state equalized value, nearly a third of its tax base in just four years, according to a Bridge analysis of state Treasury Department data.

The financial woes of top corporate executives are rarely exposed publicly. But the real estate collapse laid them bare for at least one well-known auto executive in the county.

Chrysler deputy chief executive Jim Press ran into serious personal financial problems as Chrysler veered toward bankruptcy in 2009, capturing national attention in business publications.

The Internal Revenue Service slapped a lien of almost $950,000 on his 6,800 square-foot home in Birmingham for unpaid income taxes. He also was sued for nonpayment of an $816,00 loan by a California credit union.

Further down the economic ladder, Ron Thompson lost his Madison Heights home and filed for bankruptcy after being laid off from his skilled carpenter job at a large construction firm in 2009.

He and his wife, who lost her job with a mortgage company, eventually managed to buy a foreclosed home in Macomb County.

“We were able to clean out our savings and retirement money and buy a foreclosure for cash,” said Thompson, the father of three young children. “It took all the money we had. We lost our cars and all the toys we had accumulated.

“It’s been a rough couple of years,” he said.

Even the wealthiest enclaves in the county, including Bloomfield Hills with its multimillion-dollar McMansions, have not been immune.

Bloomfield Hills’ state equalized value fell from $1.1 billion in 2007 to $768 million this year, a 30 percent drop. Many multimillion homes that went on the market in that period sold for a fraction of their asking price, if they sold at all.

Troy, the largest city in Oakland County, calls itself “The City of Tomorrow ... Today." But today isn’t looking so good in this upper middle class suburb.

It has lost $4.5 billion in state equalized value since 2007, a 29 percent drop.

It has lost $4.5 billion in state equalized value since 2007, a 29 percent drop.

The former headquarters of Kmart, once one of Troy’s largest employers, has sat vacant for years.

“Our biggest problem in Troy is our office market,” said city Assessor Nino Licari. “We’re had a tremendous loss of businesses and vacancies. It could be 25 years before we get that market back.”

Troy’s library nearly closed this year because of budget problems. It was saved last month by voter approval of a five-year, 0.7 mill tax to keep the library running.

Still, Oakland County appears ready for an economic recovery that could aid a statewide comeback, Grimes said.

County officials say residential real estate prices are beginning to stabilize, and in some areas are starting to rise, especially in its wealthier communities. And Oakland County still ranks 11th in per capita income among U.S. counties with populations of at least 1 million.

Thompson said his financial situation is starting to improve, as well, although his family income is only about half of what it was prior to his bankruptcy.

He landed a new job almost a year ago with a Detroit company that installs beverage lines in bars and restaurants and was just promoted to service representative.

“It’s looking up,” Thompson said.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!