No easy answer on Right to Work benefits

Rep. Mike Shirkey reeled off statistics about the economic growth of Right to Work states faster than the person on the other end of the phone line could jot them all down.

Shirkey, a Jackson-area Republican, also said he spent weeks anonymously calling corporate site selection specialists and asking them if their clients, mainly manufacturers, insisted on Right to Work as a condition for investing in a state.

The answer to that question, he says, was almost always “yes.”

“I’ve been astounded at the responses I’ve gotten,” said Shirkey, a leading proponent of Right to Work in the Legislature. “Michigan has no clue how many opportunities we have missed because were are not a labor-freedom, Right to Work state.”

Right to Work states prohibit union contracts that require workers to join the union and pay dues as a condition of employment. There are 23 RTW states, mostly in the South and Plains region of the country.

Indiana became the first Great Lakes RTW state after Gov. Mitch Daniels signed the measure into law in February.

Supporters of RTW say it creates jobs and promotes economic growth while giving workers the right to decide if they want to belong to a labor union.

Critics say RTW is a union-busting ploy that pushes down wages and shifts income from workers to business owners without benefiting a state’s overall economy. Union officials call the measure “Right to Work for less.”

Economists, and even some RTW supporters say it’s difficult to prove that the measure is the cause of the economic growth.

“We’re careful not to say that there is a direct causation of right to work and economic growth,” Shirkey said. “But there is a strong correlation.”

By the numbers

Tim Bartik, senior economist at the Upjohn Center for Employment Research in Kalamazoo, said it’s impossible to know whether right to work boosts employment or whether it is a “proxy” for a variety of other policies and political leanings.

“For example, if faster-growth southern states tend to adopt Right to Work, then Right to Work may be due to the underlying political culture of states, which happens by chance to be correlated with Right to Work,” he said.

Some say the push for RTW in Michigan is more about annihilating public sector unions than it is about creating more jobs in the private sector.

Last year, just 410,769 of the state’s 3.1 million private sector workers, or 12.4 percent, were covered by labor contracts, according to data compiled by economists Barry Hirsch of Georgia State University and David Macpherson of Trinity University, located in San Antonio, Texas.

But 291,852 of Michigan’s 517,000 teachers, state workers and other government employees -- 55 percent -- were covered by labor contracts.

RTW supporters don’t hide their disdain for public sector unions. They see the gains made by teachers and other public employees in collective bargaining as money transferred directly from the pockets of taxpayers to government workers. And they view local school boards and other public bodies as ill-equipped to hold off workers’ economic demands.

“I don’t think there should be public sector unions,” said Charles Owens, state director of the 17,000-member National Federation of Independent Businesses in Michigan.

However, the evidence that RTW leads to a stronger economy is mixed, at best.

A Bridge Magazine analysis of state gross domestic product, personal income and jobs data over the past two decades found that RTW states generally had better numbers than non-RTW states.

But differences in the two groups of state weren’t eye-popping, except for total job growth. And the economic performance of the 22 RTW states examined varied widely. (Indiana was included as a non-RTW state in the analysis because the measure wasn’t in place in the years studied.)

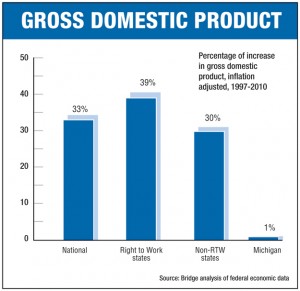

The nation’s economic output, as measured by GDP, grew by 33 percent between 1997 and 2010, adjusted for inflation, according to federal Bureau of Economic Analysis data.

Economic output in RTW states grew 39 percent in the period, while output in non-RTW states grew by 30 percent.

Output in manufacturing, where supporters say RTW is most beneficial, has barely shifted from non-RTW regions of the country over the past 20 years.

RTW states accounted for 38 percent of the nation’s manufacturing output in 2010, up just 1 percentage point from 1997. Half of the RTW states grew less than the national average of 31 percent in manufacturing output during that period.

The United States has lost 6.2 million manufacturing jobs since 1990. Nearly three-quarters of those jobs were lost in the 28 non-RTW states. RTW states lost 1.7 million manufacturing jobs in the period.

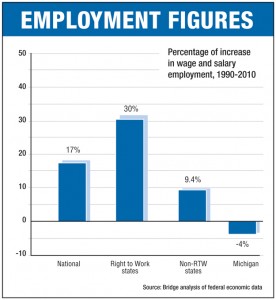

But total employment in RTW states over the past 20 years grew much faster than in non-RTW states as the U.S. population steadily shifted south.

Full- and part-time employment grew 30.2 percent in RTW states between 1990 and 2010, compared to just 9.4 percent in non-RTW states.

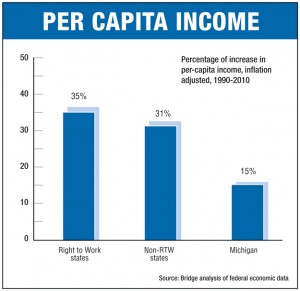

Real per capita income in RTW states over the past 20 years has grown slightly faster than in non-RTW states -- 35 percent to 31 percent.

But per capita income in non-RTW states was still an average $5,221 above incomes in RTW states, according to the Bridge analysis of federal statistics.

Union forces look to the ballot

“So-called Right to Work legislation is nothing more than a power grab by corporate special interests that will give even more profits to greedy CEOs at the expense of our jobs, our retirement security and our kids’ future,” said Todd Cook, state director of We Are the People.

Cook’s group is a backer of a proposed constitutional amendment that would protect collective bargaining rights for government and private sector workers.

Southern RTW states, in particular, have had great success in attracting Asian and European auto plants, including those of Toyota, Honda, Nissan, Hyundai, BMW and Mercedes-Benz.

Those factories have created tens of thousands of direct and spin-off jobs, including those at suppliers and at other businesses such as retail stores and restaurants.

The Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a free-market think tank which has been pushing for Michigan to become a RTW state for years, says the measure is key to the South’s economic success.

“We’ve shown that over the long haul right to work is associated with faster economic growth, more jobs and faster growing wages,” said Paul Kersey, the center’s director of labor policy. “It isn’t necessarily an overnight transformation that happens, but it’s a steady, constant growth that’s hard to deny.”

But many economists say there are numerous other factors in the economic growth of the RTW-dominated southern and western regions of the country.

Among those are better weather, cheaper energy costs, lower taxes and less government regulation. Southern states also have used billions of dollars in tax incentives to lure foreign auto plants and other manufacturing investment.

Michael Hicks, an economist at Ball State University in Muncie, Ind., also cited the “miraculous invention of air-conditioning” as a major factor in attracting population and business investment to states such as Arizona, Alabama, Mississippi and Texas.

In January, Hicks released a study on Right to Work in which he said he could find no significant impact of the measure on manufacturing wages, jobs and output in RTW states.

However, his study found that seven of 10 states that had RTW in effect for at least 10 years since 1947 showed growth in manufacturing jobs.

“It’s a fairly nuanced story,” said Hicks, who recently spoke in Lansing about the economies of Michigan and Indiana at the invitation of the Mackinac Center. “I don’t have a good answer as to whether Right to Work would help Michigan.”

But RTW supporters say Indiana’s passage of the measure increases pressure on Michigan to do the same.

“That really is a sea change in the debate,” said Rich Studley, president of the Michigan Chamber of Commerce. “By the time this fall rolls around, we could be on receiving end of a pretty aggressive economic development campaign by Indiana.”

In a 1998 study, University of Minnesota economist Thomas Holmes examined the impact on manufacturing jobs in RTW states that bordered non-RTW states.

His study found that counties in RTW states within 25 miles of the border generally had more manufacturing jobs than counties near the border of non-RTW states.

Ron Pollina, a site selection consultant in Chicago, said RTW is “extremely important” to his manufacturing clients. By adopting the measure, he said, Indiana has moved “to the top of the list” of northern states seeking manufacturing investment.

Pollina did a study in 2010 for the Michigan Economic Development Corp. recommending the state establish RTW zones in areas of the state that favored the measure or were threatened by a nearby RTW state.

His proposal hasn’t been pursued by state officials.

“The smart people (in other Midwest states) are concerned about this and they should be,” said Pollina, president of Pollina Corporate Real Estate Inc. “By becoming a Right to Work state, Indiana has positioned itself to be a major force in this region.”

But Gov. Rick Snyder has said RTW is less important in his economic development strategy of growing small businesses and adding “knowledge jobs,” which are far less subject to union representation.

Michigan State University economist Charles Ballard agreed, noting the number of workers represented by unions has declined dramatically in Michigan and the rest of the country over the past five decades.

“In a sense, the anti-union folks have won quite a bit of the battle,” Ballard said. “I think it’s just foolish to think there will be a big transformation of our economy is we make it more difficult for unions to organize,” he said.

Rick Haglund has had a distinguished career covering Michigan business, economics and government at newspapers throughout the state. Most recently, at Booth Newspapers he wrote a statewide business column and was one of only three such columnists in Michigan. He also covered the auto industry and Michigan’s economy extensively.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!