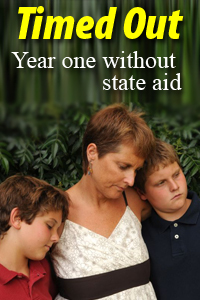

Daily life gets harder for three families

Nearly 16,000 Michigan families were banned from cash assistance last fall, in the biggest one-day reduction of welfare recipients in the state’s -- and possibly the nation’s -- history. Did those families blend into the work force? Did they lose their homes? Did they find help from charities, churches and nonprofits?

Over 12 months, Bridge Magazine and Michigan Radio are chronicling the lives of Michigan families as they struggle to adjust to Year One without aid. Here are a few updates from around the state:

Dominos keep falling

Some families lost more than cash when they were kicked off welfare.

Bonnie Baker struggled mightily, even with the about $400 she received monthly from the Family Independence Program. The 26-year-old high school dropout had three children, no job and no home after she separated from her husband.

By October 2011, Baker had received benefits for more than 48 months in her lifetime, a new limit being enforced by the Department of Human Services. Last fall, she said losing her only source of cash would “either break me or make me stronger,” she said. “I hope it makes me stronger, for my kids.”

The limit was seen as a way to save the state money, and as a way to encourage recipients to become self-sufficient.

| I | I | |

| Michigan lawmakers have embarked on a huge experiment in social welfare policy: a strictly enforced lifetime cap on cash assistance benefits. How will this affect the thousands of families receiving this aid, the communities in which they live and the course of public policy? For the next year, Bridge Magazine will provide regular reports from ex-recipients and policy-makers to judge the effectiveness of this change.I | PREVIOUS COVERAGE: 11,000 Michigan families confront the unknown |

It hasn’t worked out that way for Baker. After she lost her monthly welfare check, Baker had no way to continue payments on an old Ford Focus. Without a vehicle, she had no convenient way to travel to apply for jobs. Even public transportation was a problem, because she didn’t have money for the bus. “I’ve been doing (job) applications online,” Baker said, “but I haven’t gotten anything.”

Baker and her children moved in with a friend in Ypsilanti. Without a car, there was no way for her 7-year-old to get to school (and there's no school bus route near where they live), causing him to fall behind in class; her 4-year-old daughter had no way to get to pre-school.

Most of the family’s possessions were stored at another friend’s home. But the friend was evicted last week, and the toys and clothing she’d put aside for when her children were older were thrown in a trash bin.

A mother at 16, Baker knows she’s made some questionable decisions in her life. But now, the dominoes of her life keep falling around her, every action making it tougher for her to get back on her feet.

From the state’s perspective, Baker’s life hasn’t gotten better or worse. She was homeless before being cut off from cash assistance, and remains homeless. She didn’t have a job before welfare reform, and she is still unemployed.

Baker, however, sees the next rung of the economic ladder as further and further away

“It’s not easy,” she said. “And now with even less resources, it doesn’t help the situation.”

Bills or boots?

Since being banned from welfare, Makeda Taylor has faced plenty of questions with answers she doesn’t like.

Does the Dollar Store carry the school supplies her daughter needs?

How far behind can she be on her utility bills before she is cut off?

How should she use her last cash -- to pay a bill or get her daughter snow boots?

Three months after losing cash assistance, the 33-year-old still lives in the same apartment in Detroit, buoyed by the unemployment check she continues to receive after being laid off from her job as a cook for Detroit Public Schools. She is scrambling to find a job before her unemployment benefits run out, but has had no luck so far.

“I can’t go get things like I used to,” Taylor said. “I have to cut back on expenses in my house. I have to go to the dollar store to get paper towels and school supplies. I didn’t pay a bill so I could get my daughter a pair of boots. Now I’m in collection.

“She understands that Mommy can’t go out and buy her everything. She has to do without. But she’s a growing child. She’s got to have new clothes."

The Department of Human Services told Taylor she could re-apply for cash assistance. There were no promises, but maybe she’d qualify.

“I’m not even thinking about it,” Taylor said. “I’m going to go find me a job. I haven’t found a job around here, so I’m going to have to go out farther -- Pleasant Township, Macomb County. I would have to catch the bus.

“I have to accept this as my new life,” Taylor said. “It’s just what I have to do to support my daughter.”

Families pitching in – for now

Sharon Matthews used to get cash assistance from the state. Now, she gets cash assistance from her family.

“My family is pitching in, trying to help out,” said Matthews, of Detroit. “I try to pay as many bills as I can. It’s very rough right now.”

Her family is paying her rent; food stamps get her and her children most of the way through the month. But three months after being kicked off welfare, Matthews says she’s received cut-off notices for her electricity, gas and water.

“I go to social services, and they say I don’t qualify for assistance because I haven’t been cut off yet,” Matthews said.

Matthews was shot last year, and still carries a bullet in her leg. She’s been unable to work since the shooting, but she’s been turned down for disability.

Despite the struggles, Matthews believes her 15- and 18-year-old daughters may learn some valuable lessons.

“We’ve learned that everything we have is of value,” Matthews said. “Whether we need it now or not, we’ll need it later, so we don’t throw anything away. I’m sure they’d like new clothes but we’ve learned to accessorize because we can’t get new clothes. It’s great coping skills for doing without.

“I’m sure they know not to start families unless they’re financially able,” Matthews said. “They’re learning not to put all their eggs in one basket, because the bottom might fall out.”

Senior Writer Ron French joined Bridge in 2011 after having won more than 40 national and state journalism awards since he joined the Detroit News in 1995. French has a long track record of uncovering emerging issues and changing the public policy debate through his work. In 2006, he foretold the coming crisis in the auto industry in a special report detailing how worker health-care costs threatened to bankrupt General Motors.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!