With state welfare cuts, caseworkers fear less time to help families

As the legislature contemplates next year’s budget and the two state welfare agencies prepare to merge to create the largest department in Michigan, the state must remember that a majority of recipients are children in need ‒ Pat Sorenson, senior policy analyst at the Michigan League for Public Policy.

Toni Scott of Grand Rapids woke up one morning in 2005 and her arm felt numb and sore, as if she'd slept on it wrong. It turned out she had multiple sclerosis. The debilitating disease attacked her nervous system and shut down her ability to run the cleaning service she started that brought in about $1,200 a month.

It also pushed her to a place she’d been able to avoid – the welfare office.

Sick and disabled, Scott had to pack up her pride behind a pained smile and go to the state Department of Human Services in Kent County to ask for help getting back what the disease stole from her – money for food and bills.

She learned quickly that the DHS office can be a tense place, a tinderbox of emotional people often none too happy that they have to ask for help and state workers sometimes overwhelmed by the volume of those asks.

Recently, the morale in the welfare office in Grand Rapids sunk even lower, Scott said.

In February, the state cut 100 workers from the Michigan Department of Human Services – 35 worked at a Kent County online processing center in Grand Rapids that was closed. A second processing center, in Detroit, also closed. That left one remaining center, in Lansing, to handle 350,000 applications for food stamps and cash assistance each year.

The $7.5 million in staffing cuts to DHS came as the state upped overall spending between 2013 and 2014 by 9 percent from $47 billion to about $51 billion.

The state is also planning to merge DHS with the Department of Community Health in April. The move will create the biggest department in the state, raising questions about whether more job cuts may occur.

The DHS cuts and merger come at a time when workers say they are already burdened with high caseloads, are finding it challenging to meet deadlines for processing application requests, and as poverty indicators suggest that DHS services remain in high demand. State officials acknowledge that the claims applications handled by the now-closed processing centers will now have to be processed by caseworkers.

“Why cut the people who help those who need the most help?” said Scott, 55, of Grand Rapids.

Not bigger government, better government

The Department of Community Health will merge with DHS on April 10, creating the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. The new department will have about 14,000 employees.

Nick Lyon, director of the Department of Community Health and interim director of the Department of Human Services director, said in a recent column for Bridge that merging the departments will lead to efficiencies, making it possible for clients to get more services from one central agency.

“We will be able to address health and human services together under one department, and to treat the whole person, not just pieces of a problem,” Lyon wrote. “This is our opportunity to affect positive change for families across our great state, and we are committed to doing just that.”

It is unclear if that means additional layoffs.

“The intention of the merger is not to reduce positions, but to provide better and more coordinated services,” said Bob Wheaton, spokesman for DHS. “It’s possible there may be some efficiencies found, but at this point we haven’t made any decisions to lay off people.”

Next year’s proposed budget recommends eliminating eight positions in the Supplemental Security Income division that handles payments to disabled residents. DHS hopes to avoid layoffs by moving those workers into other positions, Wheaton said.

Statewide, about 3,300 caseworkers handle food stamps and cash assistance cases for vulnerable people and families, helping residents update required documentation, get benefit payments and navigate the system. With the recent cuts, these field workers inherit the job of helping to process the 350,000 online applications a year.

Caseworkers may have more tasks, Wheaton acknowledged, but their ranks purposely were not cut.

“Keeping the same number of caseworkers in … local offices is a priority because they directly serve the state’s children, families and individuals in their own communities,” he said. “It will continue to be important with the creation of the merged Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.”

‘I will survive’

Since getting sick, Toni Scott has found that public assistance helps to support her family, but is no boon.

Scott’s daughter is now a 23-year-old adult, so Scott gets food stamps only for herself these days. In February, that came to $53.

To survive, she goes to food trucks that offer free fresh produce and makes sure she is at a local church on the third Saturday of the month to get free groceries.

She then makes her own sauces, gravies and stews and freezes them for later.

Scott picks up an occasional $80 by showing others how to survive, too, by doing cooking demonstrations for Our Kitchen Table, a group that teaches disenfranchised populations gardening, healthy eating and environmental protection in greater Grand Rapids.

When local caseworkers told her about the DHS cuts, she wondered if the state’s decision makers understand the possible ill effects on clients.

Data is not yet available on whether the February DHS budget cuts have slowed service to needy families. But even before the cuts, union officials say, some DHS field office were not meeting requirements for timely responses to requests for public assistance.

For example, DHS is supposed to respond to applications within 30 to 45 days (within seven days in cases of emergency). In Wayne County in January and February, DHS workers were able to meet those deadlines about 89 percent of the time, which is below the 95 percent threshold set by the U.S. government, according to UAW Local 6000, which represents DHS caseworkers across the state.

Poverty high, welfare cases lower

The state made the decision to cut DHS staffing by $7.5 million in June 2014. That was the same year DHS saw a drop in the number of temporary cash and food stamps cases.

From 2013 to 2014, cash assistance cases fell from roughly 130,000 families to 90,000, and food stamps cases fell from 1,775,646 to 1,680,721, DHS data show.

The dip in Michigan welfare cases is attributed to the state’s economic growth as well as some families being cut off from cash assistance because they hit the maximum 48-month limit, state data show.

But a drop in cases does not necessarily mean a drop in need for DHS workers, said Pat Sorenson, senior policy analyst for the Michigan League for Public Policy, a nonprofit based in Lansing that advocates for economic equity.

More than two million of Michigan’s nine million residents were enrolled last year in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, commonly known as the food stamp program. And 1.7 million residents received Medicaid, the most ever, according to state Department of Community Health. More than half of Michigan Medicaid clients are children.

Across the state, about 24 percent of Michigan children live in poverty – and 7 percent lived in families with no employed adult in 2013, the same as in the year prior, according to the most recent information from the Kids Count Data Center, which studies the well-being of children nationwide.

“These are important human services where there is contact everyday with families in great need,” Sorenson said. “We can’t let this (state agency) merger be an excuse for getting to a point where we can’t appropriately serve families.”

An unhappy place

Ray Holman, spokesman for the UAW Local 6000, said giving caseworkers more administrative duties takes time away from helping needy children and families.

“We support trying to find efficiencies. We’re taxpayers and want tax dollars to go as far as possible. We’ve been saying for years we have too many managers,” Holman said. “We need to put the resources with the people who actually deal with the public.”

Holman’s local held a protest in February at a DHS office on Detroit’s west side. Caseworkers there on average handle as many as 900 cases each, according to the union.

It is not a happy place.

On a recent afternoon, a handful of people slumped in blue chairs waiting to be called by a security guard to approach a customer service desk that is encased in ceiling-high glass.

Two social workers sat at a desk outside the enclosure answering questions from people who didn’t have appointments though a sign on the wall reads, “No walk ins. Appointment only.”

Across the dingy white-and-blue-checkered linoleum floor, a row of computers line the back of the room.

That’s where Mellisa Cardwell, 33, spent more than an hour and a half filling out an online application for services. Cardwell works in customer service at a healthcare call center, but still gets food stamps and publicly-funded health care to make ends meet for herself and her two children.

“I called on Monday and still no call back and it’s Friday. So I had to come down here. I totally dread coming here,” she said.

Cardwell said she had to wait 30 minutes to get “somebody to help me with the computer and then they had an attitude. I understand,” she said. “They’re overwhelmed.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

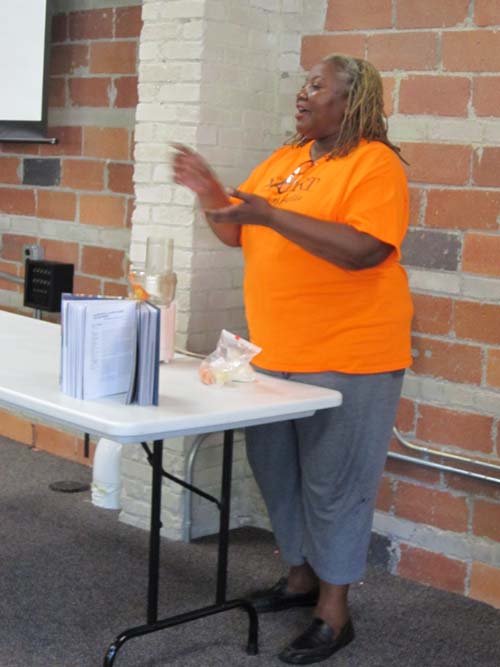

Toni Scott (supplied photo), 55, who receives DHS benefits in Grand Rapids, fears workforce cuts will slow help to needy Michigan families, increase crime.

Toni Scott (supplied photo), 55, who receives DHS benefits in Grand Rapids, fears workforce cuts will slow help to needy Michigan families, increase crime. Mellisa Cardwell, 33, of Detroit, recently spent more than a hour and half at a DHS office applying for assistance. She said DHS needs more workers in the field.

Mellisa Cardwell, 33, of Detroit, recently spent more than a hour and half at a DHS office applying for assistance. She said DHS needs more workers in the field.