Welfare reform leaves families without a net, and off the radar

Three months after the launch of an aggressive welfare reform, Michigan has kicked more people off the dole than expected and saved the state millions of dollars. How the approximately 15,000 families cut off from cash assistance are surviving, though, isn’t as clear.

We may never know. The state isn’t monitoring the impact on those families, and social service agencies don’t have a way to do it themselves.

“All policies have consequences, positive or negative,” said Gilda Jacobs, president of the advocacy group Michigan League for Human Services. “We need to make sure the policy is not making people’s lives worse.”

The reform instituted in Michigan’s welfare system in October was unprecedented nationally. No other state had kicked so many people off assistance in such a short amount of time, with such little notice. No one knew what would happen. It was a massive social experiment that could transform the Michigan economy or fill the state’s homeless shelters and prisons.

In a year-long series, Bridge Magazine and Michigan Radio will report on the results of that experiment. We’ll chronicle the lives of families as they adjust to life off welfare, and assess the economic impact of reform on state government and nonprofit charities.

In a year-long series, Bridge Magazine and Michigan Radio will report on the results of that experiment. We’ll chronicle the lives of families as they adjust to life off welfare, and assess the economic impact of reform on state government and nonprofit charities.

“I don’t know what my last option will be,” said Sharon Matthews of Detroit, whose family lost cash assistance in the fall. “To move in with family? I only have one sister in Michigan and she’s not in a position to take in another whole family. My family can’t help pay the rent forever. I’m praying I don’t end up in a shelter for women and children, but I may have to.”

Welfare cases plummet

The Family Independence Program, run by the Michigan Department of Human Services, provides cash monthly to low-income families with minor children, as well as to pregnant women. In Michigan, a family of three must make less than $815 a month (less than $10,000 a year) to qualify for help.

| I | I | |

| Michigan lawmakers have embarked on a huge experiment in social welfare policy: a strictly enforced lifetime cap on cash assistance benefits. How will this affect the thousands of families receiving this aid, the communities in which they live and the course of public policy? For the next year, Bridge Magazine will provide regular reports from ex-recipients and policy-makers to judge the effectiveness of this change.IPREVIOUS COVERAGE: 11,000 Michigan families confront the unknown |

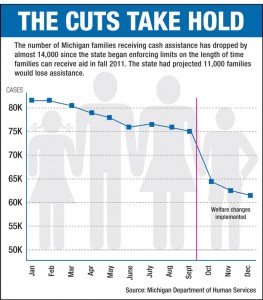

The number of Michigan families receiving aid skyrocketed during the state’s decade-long recession, reaching a peak in early 2011 when one in every 42 Michigan residents was receiving cash assistance.

This fall, the state placed a lifetime limit of 48 months on cash assistance, and began enforcing a 60-month limit that was set by the federal government, but had been ignored.

The impact was dramatic. DHS had estimated that slightly more than 11,000 families would be kicked off welfare by the policy. But in the first month alone, almost 13,000 families were removed from the rolls; by the end of December, the number of FIP cases was down 15,799 -- a drop of 20 percent in three months.

Counting family members, more than 54,000 Michigan residents (most of them children) lost cash assistance in three months.

In some cases, families lost cash assistance, but gained some of it back in food stamps. Food stamp levels are based on income, and cash assistance was counted as income. DHS spokesman Dave Akerly* gave an example of one Michigan family that lost $493 per month in cash aid, but saw their monthly food stamp allotment increase by $240.

“It (more food stamps) doesn’t pay the rent, but it helps,” Akerly said.

Food stamps are a federal program, so an increase in food stamps does not hurt the state budget.

The cash assistance decline is saving the state big bucks. FIP is funded primarily with federal dollars, but the state paid the tab for families over the federal 60-month lifetime limit, explained Akerly. In December, the latest month for which statistics are available, the state doled out $10 million less in cash assistance than it did in an average month in the year before the reform.

What of the families?

Less is known about the policy’s impact on people.

Advocates of reform argued that when government checks stopped, families would find jobs. Rep. Ken Horn, R-Frankenmuth, who shepherded the reform bill through the Legislature, said that former recipients would “pick up a hammer or a paint brush and man up and feed their family.”

There were 43,000 jobs created in the state between September and December, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. But are former welfare recipients getting jobs? No one knows.

Critics worried that families would become homeless, but that hasn’t happened so far.

Barb Ritter, project manager at the Michigan Coalition Against Homelessness, says there hasn’t been a large increase in people seeking shelter, and she doesn’t know if families who were kicked off welfare are among the families at shelters across the state.

Three months after losing cash assistance may be too early to tell what will happen to the families. “It normally takes a while for people to actually go homeless and both DHS and MSHDA (Michigan State Housing Development Authority) are trying to launch some bridge housing supports for the most vulnerable in the group,” Ritter said. “Homelessness is normally a lagging indicator.”

“There are always unintended consequences,” MLHS' Jacobs said. “I’m not sure we have enough data to know whether it makes sense to kick people off.”

Why not get the answers?

There are ways to monitor the impact, said Luke Shaefer, assistant professor of social work at the University of Michigan. Many of the families kicked off cash assistance continue to be eligible for other assistance programs, such as food stamps, or child care assistance, that are also administered by DHS. Some of those programs, including food stamps, require recipients to report income. The department could cross-reference the data to analyze whether those who were kicked off welfare eventually increased their income. The same could be done with Child Protective Services to discover whether the loss of cash assistance increased child abuse.

Akerly said he knows of no plans to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the impact of the welfare reform on those who lost benefits. Akerly did say that DHS would examine the impact on a “case by case” basis.

Melissa Smith, senior policy analyst for the Michigan League for Human Services, said DHS is “very defensive” about tracking the families, but that monitoring is vital for policymakers to determine the true impact of the reform; when some are saying the families will flow seamlessly into the workforce and others are saying they’ll become homeless, data should be used to find the truth. Otherwise, “people are just going to disappear and they’re just going to not know what happened.”

Senior Writer Ron French joined Bridge in 2011 after having won more than 40 national and state journalism awards since he joined the Detroit News in 1995. French has a long track record of uncovering emerging issues and changing the public policy debate through his work. In 2006, he foretold the coming crisis in the auto industry in a special report detailing how worker health-care costs threatened to bankrupt General Motors.

* DHS Spokesman Dave Akerly's name was misspelled in the original edition of this story.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!