Higher ed is key to a state’s success, and should be supported

Across the nation, public policymakers are starting to let data drive decisions. That’s why the most successful states – states where you can live long and prosper, to borrow a phrase – are those that are doing more to prepare, retain and attract young college graduates.

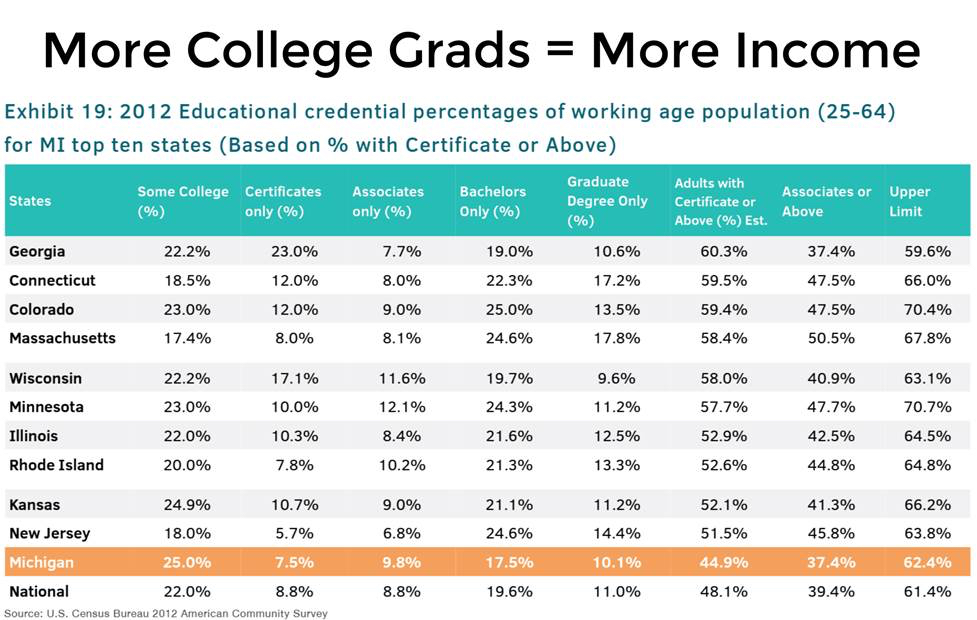

The states with the highest per capita incomes and the longest life spans tend to be those with large percentages of college graduates.

That fact seems to be a problem for the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, which argues that average citizens are better off when taxes are low and public goods – including state support for higher education – are severely limited. Mackinac Center writers, in a recent Bridge opinion piece, argued that Michigan shouldn’t be taking steps to invest more in higher education, because it wouldn’t result in lower tuition and that the investment wouldn’t result in more college grads choosing to stay in the state anyway.

Missing in both arguments were important factors that the authors ignored.

First: The cost of providing a public university education to a Michigan student is virtually the same as it was in 2002, after adjusting for inflation. Tuition is up because state support for those students is down.

Second: States that don’t prepare, attract or retain college graduates are poor relative to more educated neighbors. So a state needs to do all three to be in the front ranks of prosperity – get its students ready for college, graduate them, and then keep them here and attract more of their colleagues.

Let’s look at the first issue. A nonpartisan Michigan House Fiscal Agency analysis showed that from 2001 to 2014, after inflation, 80 percent of tuition prices were attributable to state funding reductions, and nearly 100 percent when factoring in institutional financial aid. The cost of a public university education for a Michigan student – state support plus tuition rates – has been essentially flat since the 2001-02 school year after adjusting for inflation.

In the 2001-02 school year, state universities received $12,468 from the state for each state student enrolled, and charged on average $6,543 to a state student for tuition. The total cost in 2015 dollars: $19,011.

In 2014-15, state universities received just $7,496 from the state for each Michigan student, a 40 percent cut in state support per student. The average in-state tuition increased to $11,454 per student. Total cost for an education of a Michigan student: $18,950. After adjusting for inflation, that’s $61 less than in 2001-02.

Some students, however, are paying significantly more for tuition than they used to, and are helping to subsidize others. Those would be out-of-state and international students. Thanks to good management, Michigan’s public universities are considered some of the best in the nation as a group. That high quality allows them to charge a premium for the education students from other states and other nations are receiving, and helps support students from Detroit to Ironwood.

Which brings us to point two. Attracting these out-of-Michigan students also gives the state a chance to hold onto them to bolster our state’s lower tier ranking in college attainment. Today, Michigan ranks 34th among the 50 states of those over 25 years old with a college degree. It also ranks 34th in per capita income, and 35th in average life expectancy.

The states with the highest per capita income and longer life spans have more college graduates in their population mix. (In the Midwest, that would be Minnesota, ranking 10th nationally in education attainment, 9th in per capita income and 2nd in life expectancy.)

Now, Michigan’s universities can’t make students stay and take jobs here. That requires, first and foremost, the kinds of cities that today’s graduates want to work, live and play in.

Unfortunately, when compared to other states, Michigan is falling behind in that race. Massive cuts to revenue sharing have meant our cities just don’t stack up to Minneapolis, Chicago, Washington D.C. or San Francisco in the quality of life young college graduates are looking for.

Lack of mass transit dollars mean college grads who increasingly want to get by without a vehicle are limited in their Michigan location decisions. It all adds up to a brain drain.

The Mackinac Center’s ideologically-driven assertions regarding the value of state investment in public higher education conveniently failed to focus on the right variables. The fact is, data from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis demonstrate that there’s a positive correlation between state per-student funding for universities and state per-capita income. There is, more importantly, an even stronger positive correlation between the education level of states (as determined by the percentage of citizens over 25 with a bachelor’s degree) and state per-capita income.

The data are clear: supporting public universities through state investment will drive up Michigan’s per capita income.

The Mackinac Center wants to argue one-dimensional approaches – that more state support for higher education won’t result in lower tuition for in-state students, and that investment in higher education won’t lead to more college-educated people choosing our state. But it’s easy to see that states that invest in higher education tend to have lower tuitions. And it’s obvious that if we don’t create college graduates, considering how poorly we are doing in creating an environment that attracts them, we will fall further and further behind.

Without sufficient numbers of college graduates, companies that need them won’t stick around, and certainly won’t move to Michigan. And we won’t move the needle on our current low per capita income numbers.

Investing in our universities and our cities, two areas the state has slashed the most in the last 15 years, is the best way to increase prosperity for our state.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Daniel J. Hurley is the CEO of the Michigan Association of State Universities.

Daniel J. Hurley is the CEO of the Michigan Association of State Universities. Chart prepared by the Michigan Association of State Universities. (Click to enlarge)

Chart prepared by the Michigan Association of State Universities. (Click to enlarge)