Michigan seeks to cash in on CBD craze, but hemp harvest not without hiccups

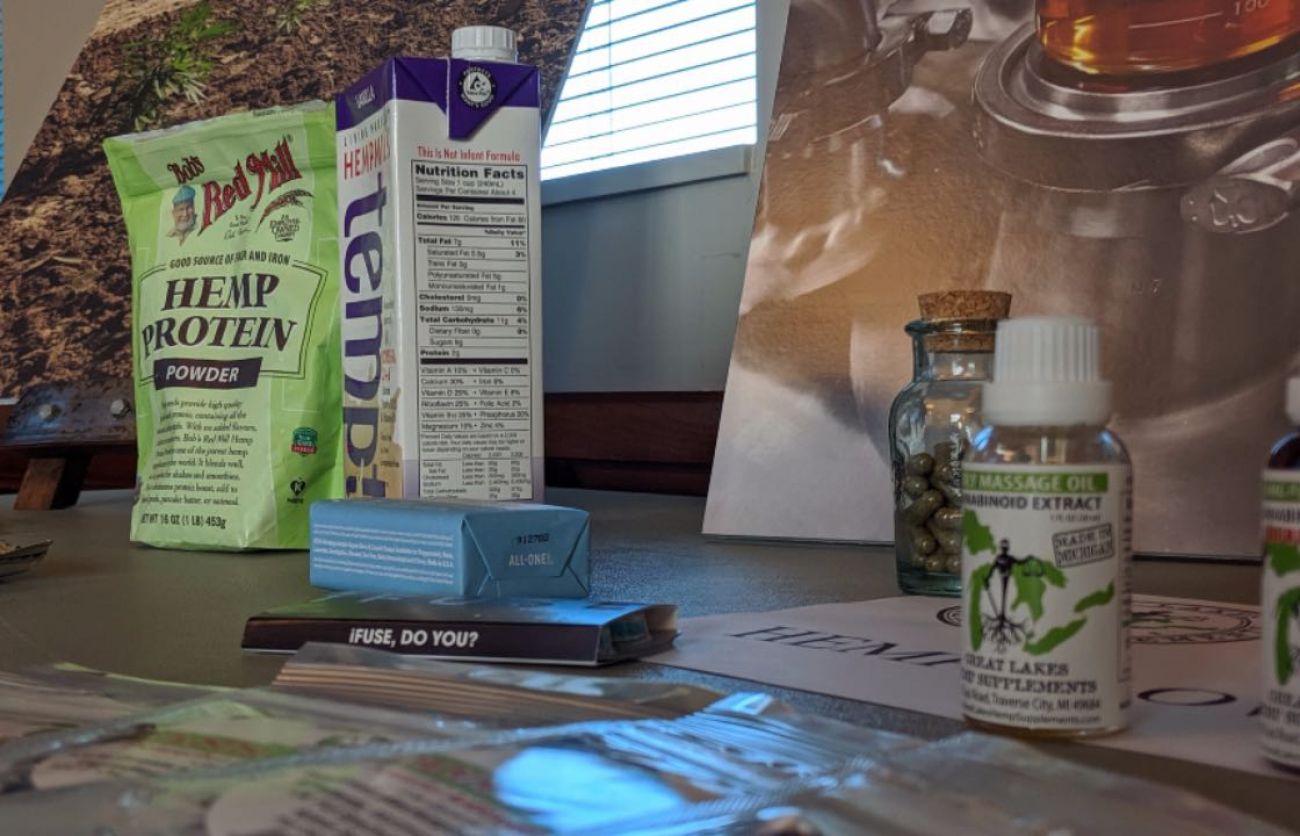

LANSING — Topical cannabidiol creams are competing for shelf space at Kroger and Whole Foods. Wellness sprays are sold over the counter in Walgreens and other national pharmacies. And Family Video is even selling CBD next to DVDs.

CBD has gone mainstream, and Michigan farmers hope to cash in on the craze this fall as they harvest the state’s first-ever legal hemp crops.

While farmers say there were growing pains during Michigan’s inaugural grow, David Conner of Paw Paw Hemp is expecting to turn a profit on 26 acres he and a business partner are growing on a southwest Michigan blueberry farm.

“When any type of crop is in the middle of harvest, that’s probably when you’re going to get the lowest price point,” Conner said.

“But even at the lowest price point, it’s still better this year for us to be in hemp than corn.”

Although there are plenty of warning signs, hemp could turn out to be a bright spot in an otherwise dreary year for Michigan farmers, who have contended with heavy rains and plunging prices that prompted federal authorities to declare disasters in five counties along the Indiana border.

Conner is one of 564 hemp farmers licensed to grow hemp this season under a pilot program by the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. The state also licensed 423 processors and handlers to help bring the inaugural crop to market.

Hemp is a strain of the cannabis sativa plant but contains no more than trace amounts of the psychoactive element of marijuana. It had been shunned for decades because of its relationship to pot, but the federal government is in the process of establishing rules for commercial processing and production allowed under a 2018 law.

Michigan is “uniquely positioned” to grow, process and manufacture industrial hemp, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer said in April as the state launched its pilot program while waiting for long-term federal rules.

“We are one of the nation’s most agriculturally diverse states — growing 300 different commodities on a commercial basis — making it a natural fit,” Whitmer said.

States are quickly changing industrial hemp laws to reflect the changing landscape. At least six states approved laws in 2018 to create hemp research or industrial hemp pilot programs, while farmers in at least 34 states harvested some 500,000 acres this fall.

It hasn’t always gone smoothly. Nationwide, some experts say a “massive oversupply” of farmers planting what some billed as a miracle crop will plunge prices.

Michigan’s first growing season also was problematic for some farmers who didn’t plant their full crop or lost significant acreage because they were experimenting with soil quality, weed maintenance, feeding schedules and harvest techniques to grow the kind of CBD flower that processors and manufacturers will want for retail products.

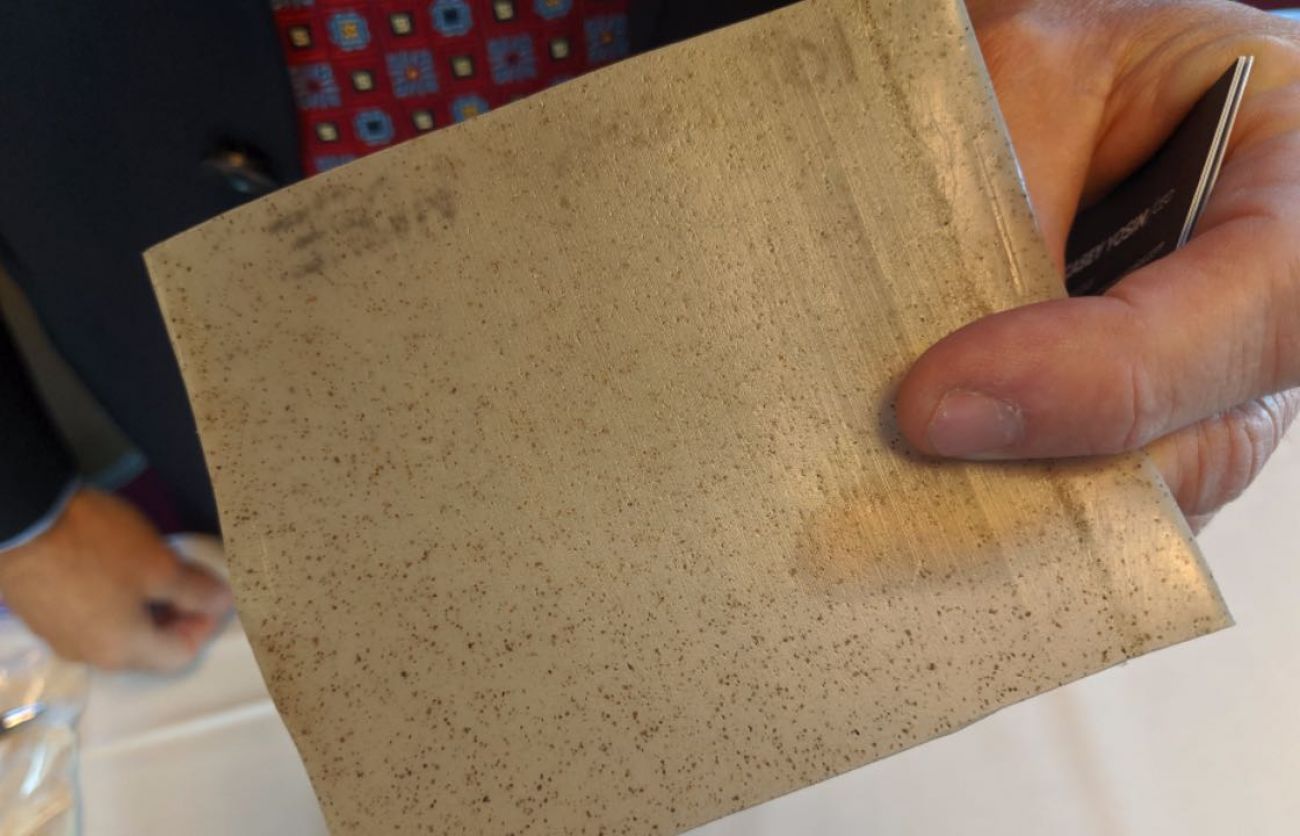

“It’s all a learning process,” said hemp processor Casey Yosin, founder and CEO of Total Health Co. of Auburn Hills in Oakland County. “Everybody is kind of learning on the fly.”

Conner and his business partner had planned to plant 40 acres of hemp on their Paw Paw farm but ended up planting just 26 acres this season because of what he called unforeseen “genetic challenges” with the crop.

Claims that hemp would “grow like a weed” proved to be exaggerations, he said, describing hiccups with soil conservation and weed management. And harvesting the crop, an ongoing process he anticipates will take 26 days, proved “extremely labor intensive.”

Conner said he and his partner are using a daily harvest crew of 22 workers to prepare the product for shipping and at least 10 others working the field.

The average grower will spend between $5,000 to $10,000 per acre on their fields this year, experts said Monday in a roundtable organized by the Industrial Hemp Industry of Michigan.

But farmers are anticipating returns of between $10,000 to $12,000 an acre for the plant flowers used to create CBD oils marketed as wellness products.

“It’s all about the supply chain,” said Yosin, who told reporters plans are in the works to build a major hemp processing facility at an undisclosed location in mid-Michigan.

“If farmers can get in with a good processing group that actually has outlays for the product, then you’ll be able to demand a pretty good premium.”

CBD is typically sold as a health and wellness product. But like its cousin, marijuana, former prohibitions have stymied scholarly research into its efficacy or risks. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved only one CBD prescription drug, a product used to treat rare and severe forms of epilepsy, and warns of “unanswered questions about the science, safety, and quality of products containing CBD.”

But Michael Thue, a certified medical assistant who founded Great Lakes Hemp Supplements and the Center for Compassion in Traverse City, said he’s seen CBD prove effective for treating migraines, arthritis and other ailments in residents of all ages.

“CBD has rapidly grown in awareness,” Thue said. “I’ve been doing CBD research for the last nine years here in Michigan under the medical marijuana law. When I would speak eight years ago, nobody knew what CBD was.”

In an online paper, Harvard University Medical School struck middle ground, writing that some providers have come under scrutiny for “wild, indefensible claims, such that CBD is a cure-all for cancer, which it is not. We need more research but CBD may be prove to be an option for managing anxiety, insomnia, and chronic pain.”

Michigan’s fledgling hemp industry remains a tiny fraction of the state’s agricultural portfolio. By comparison, Michigan farmers harvested 1.9 million acres of corn in 2018, according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service.

The state began licensing medical marijuana growers in July 2018, but limits for that crop are based on total plants, not acres. There are currently 127 medical marijuana growers authorized to cultivate up to a combined 175,500 plants, according to state data. Michigan is set to begin licensing recreational marijuana businesses in November.

While most first-time Michigan farmers are expected to sell flowers for CBD products, advocates say the hemp plant has multiple uses and that could provide a secondary revenue source in future years.

The seeds could be used for foods, animal feeds, shampoos or paints. The stalks can be used to make paper materials, clothing and other textiles or building materials.

“The entire plant has a revenue opportunity,” said Gary Schuler, founder and chief executive officer of GTF LLC based in Grand Rapids. “This could be life-changing for those farmers. And I’m talking about even the roots. There’s value in that root material."

Schuler’s firm is working with another West Michigan company on new technology to dry and pulverize hemp and other plant-based materials into smaller forms that could be used in a variety of applications.

Tiny hemp particles can be used to replace polypropylene in plastics, creating a less carbon-intensive version of the product that does not rely on petroleum-based fossil fuels, he said. “Just think about the environmental impact of that.”

Schuler and his partners have already worked to create a water bottle prototype made from the clean plastic that is antimicrobial and won’t melt at high temperatures.

While farmers are completing their first legal harvest, Michigan is in the process of sending license renewal notices for its pilot program, which could continue for a second growing season if the federal government hasn’t finalized national rules by the spring.

Michigan will likely need to update state law once those federal rules are announced, and it will be required to submit a commercial hemp plan to the U.S. Department of Agriculture for review, said Gina Allessandri, industrial hemp program director for the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

In the meantime, farmers can still apply for year two of the pilot.

“We have not restricted the number of participants or the amount of acreage,” Allessandri said. “We wanted to let as many people in and learn as were interested. We didn’t want to restrict anybody from it.”

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!