Detroit, allies caught on blight treadmill

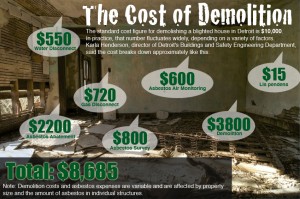

The numbers are inescapable: Estimates of just how many blighted buildings still stand in Detroit– most of them houses past rehabilitation, nests of crime and the most visible signs of the city’s distress – range from 30,000 to as many as 70,000. It costs about $10,000, on average, to take down one of them. Which means that Detroit needs anywhere from $300 million to $700 million to get the job done, when its entire city budget for next year is $1.1 billion, with a $200 million deficit.

It would be a lifetime achievement for any politician to pull off in a city with healthy finances and a relatively clear agenda, neither of which Detroit has at the moment, and is unlikely to have at any time in the near future.

So what is to be done about Detroit blight?

John George has one solution: Do it yourself.

George founded Motor City Blight Busters 24 years ago, when he got tired of waiting for the city to close down a vacant structure that was being used as a crack house. One day, he went down the street with plywood and boarded it up himself, with help from the neighbors. Ever since, he’s been wrestling with decay, sometimes as a guerrilla fighter.

“I’ve been through a lot of mayors, and here's my point: If government was the answer, we'd all be laying on the beach,” he said. “We don't need any more of that crap. It's we the people. We love Mayor (Dave) Bing, but mayors come and go. Real Detroiters stick and stay.”

Motor City Blight Busters has become respectable enough over the last two decades that they’re now an accepted part of the establishment. On Saturday mornings, volunteers -- from the neighborhood, from church groups, from corporate community-service initiatives -- gather at the Motor City Java House on Lahser Street, the group’s clubhouse, to get their marching orders for the day’s project.

The Java House sits on the same block with the Redford Theater, the Artist Village and other examples of the group’s dedication to attacking Detroit blight one project at a time.

“Without Motor City Blight Busters, this whole corner would be rubble,” George said, leading a visitor on a quick-walking tour of the area. “Our goal is to save the world, and we're starting with Detroit.”

On a recent sunny Saturday, the group convened on a neighborhood a few blocks northwest for a “clean up/board up,” targeting a once-healthy street where the cancer was starting to spread. They mowed overgrown lots, nailed plywood over the doors and windows of two houses standing open to the elements, and otherwise reasserted a sense of order to what is still a tidy and attractive street.

But the biggest job for this season is “the Santa Clara seven,” a group of houses marked for demolition on the same block as the theater and other Blight Buster successes. George was off to the city to get final demolition permits for them, and once they’ve been taken down, the plan is to groom the large vacant tract and jump onto the latest craze in the inner city – farming. George wants to feed his neighbors and be part a new paradigm for this sprawling, radically changing city.

“We need a Marshall Plan, frankly, where we suspend the rules and bullshit,” he said. “We need to be able to tear down immediately 80,000 residential and maybe 10-15,000 commercial buildings. Blight is like a cancer. If you don't get rid of it, it will get rid of you. This would be a radical chemotherapy blast of blight removal.”

And what would Detroit look like afterward? Like no other city in America.

“Greenhouses, walking trails, sunflowers, cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers, art, barbecue pits,” George said. “We can have everything we want – there's plenty of room.”

City stuck in 'catch-up' mode

In city offices, the question is focused more narrowly: What is to be done about Detroit blight today?

“We’re constantly playing catch-up,” said Karla Henderson, group executive for planning and facilities for the city, and its go-to spokeswoman on the problem. “We have to stop the vacancy rate.”

Detroit’s vacancy rate is perhaps its most obvious single characteristic, and has been well-documented for years. The city’s population peaked in the 1950s at more than 2 million, and has since fallen to 713,777, leading to wide swaths of vacant lots and abandoned buildings. Maps of census data compiled by Data Driven Detroit shows the extent of the loss, by vacant lot and by vacant housing, much of it unlikely to be recovered. The standard figure city officials quote is that 40 square miles of the city's 139-square-mile footprint is vacant, scattered throughout. Only New Orleans is in the same league.

Blight eradication has been tackled by virtually every mayor who’s served since the 1950s. Federal strategies of “urban renewal” started after World War II and in Detroit, historically black neighborhoods were cleared by wrecking balls to make way for freeways and, it was hoped, better housing for residents. Coleman Young, Dennis Archer, Kwame Kilpatrick and current Mayor Dave Bing have all made promises to get tough with blight, and to be sure, thousands of empty buildings fell on their watch. But thousands more have taken their place.

The economic collapse of 2008 brought a wave of unemployment, mortgage default, foreclosure and evictions that made the problem appreciably worse. Henderson said it has reached the point that she’s willing to explore strategies that would allow those at risk of leaving their homes -- for instance, people in arrears on taxes -- to stay put, while alternate collection strategies are pursued.

“Some people leave because they think they’ll be evicted,” Henderson said. “We need to figure out how to stop that loop.”

Vacancies mean lots of paperwork

Doing so is important because the other end of the process isn’t good for anyone. The city loses a taxpayer, a neighborhood loses a resident and everyone gets a headache.

Henderson, who estimates the number of blighted homes in the city at 30,000, said the process for demolishing a blighted home is long and frustrating for all. A best-case, “perfect-world” scenario takes about nine months, from initial complaint to the arrival of bulldozers. There are few of those, Henderson said.

In emergencies, the city can move faster. But most demolitions require a laborious paper trail of inspections and notifications and other approvals before the city can take action to demolish a vacant building.

“We have to adhere to state housing code,” said Henderson. “One of the things I’d ask the state to consider is streamlining the process.”

For example, she said, if the city pulls a title on a house and discovers it’s owned by a person whose last known address was there, and the house is vacant and apparently abandoned, why should the city then have to send two registered letters to that address, knowing the chance of the mail being picked up by the owner is infinitesimal?

“Obviously, they’re not interested in the property,” Henderson said. “Why can’t the code change?”

Henderson’s department may get some help from a bipartisan series of bills (Senate Bills 1096, 1097, 1098, 1099, 1100), which toughens the penalties for property owners who ignore violations issued by the city. It also speeds the process by which the city can obtain a lien against property owned by a non-compliant owner, leading to faster possession and demolition.

The legislation passed out of committee and is awaiting action on the Senate floor. The Senate is scheduled for only two session days this summer, however: July 18 and Aug. 16.

Staff Writer Nancy Nall Derringer has been a writer, editor and teacher in Metro Detroit for seven years, and was a co-founder and editor of GrossePointeToday.com, an early experiment in hyperlocal journalism. Before that, she worked for 20 years in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where she won numerous state and national awards for her work as a columnist for The News-Sentinel.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!