GOP hunts votes in the D

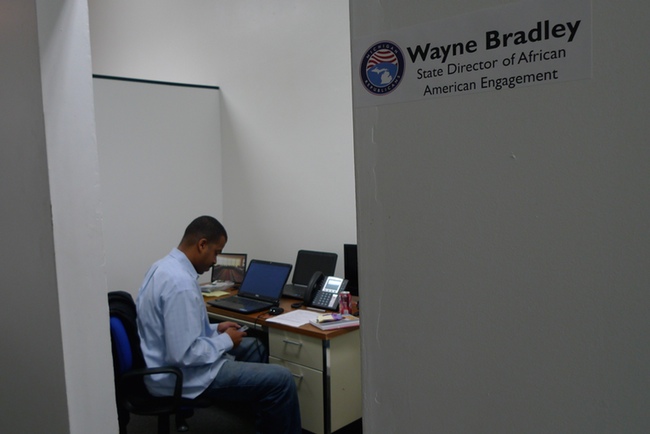

It’s not hard to get a parking spot outside Detroit’s Republican headquarters on Livernois Avenue, even on what Wayne Bradley describes as a big volunteer day for the party’s get-out-the-vote effort this fall. Inside, Bradley and two others are calling registered Republicans in Wayne County, seeking support for the party’s ticket. It’s the scut work of politics, but Bradley, the state director of African-American engagement, isn’t letting it get him down.

“Can I count on your vote? Did you receive your absentee ballot?” he asks voter after voter. About half say yes. Others aren’t in the mood to chat. Bradley thanks them all.

But he’s just killing time until his media-relations person arrives and he can hit the road for African-American engagement, right here in the overwhelmingly Democratic city where he was born. With a spring in his step, Bradley is out the door and headed down the street to Dixon’s Barber Shop, where he’s been getting his hair cut all his life.

This stretch of Livernois, between Seven and Eight Mile Roads, was once renowned for its shopping, known as the Avenue of Fashion. That was a long time ago. The area is having a bit of a renaissance – a few storefronts are starting to fill with solo operators and entrepreneurs. No chain stores, but fewer empty storefronts, a glass-half-full sort of neighborhood, the way Bradley sees it.

Dixon’s is a natural place for community engagement. With occupants sitting under capes and barbers wielding scissors and clippers, the news of the day can be hashed out, sporting events taken apart and the world’s problems solved, or at least discussed. A Barack Obama poster – from 2008 – hangs on the wall.

Bradley is undaunted. He shakes hands and passes out a piece of literature touting Gov. Rick Snyder’s work on behalf of the city; he has “put the reinvention of Detroit among his highest priorities...Increased access to affordable healthcare for 470,000 Michigan citizens.”

Barber Kenneth Reid listens for a few moments as Bradley talks of the good things happening in Detroit – street lights coming back on, more police on the street. Reid listens politely as he works on the head in front of him. But he’s not agreeing with Bradley’s pitch, and when asked directly if he is a Republican, Reid answers, “Actually, I am not.”

Like selling socialism in Salt Lake City

There could hardly be a more daunting task than selling the Republican Party in Detroit. With enormous African-American majorities, the city votes so reliably Democratic that November elections are usually anticlimactic; the real action takes place in the Democratic primaries for local races months earlier.

From time to time, national Republicans make noise about widening the tent and crafting a more aggressive pitch to African-American and Hispanic voters on the conservative issues they see as marketable ‒ school choice and opposition to same-sex marriage, for instance.

So it was that Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, a fast-rising star in the party, came to open this office last December. A few days later, in a column for Politico, co-authored by RNC chair Reince Priebus, Paul wrote, “It’s time to give the Republican ideas of free enterprise a try in the Motor City. It’s time we offer real solutions that leave more money in the hands of those who earned it. It’s time for the GOP to share our message of less government and more individual freedom.”

Hence the hiring of Bradley, a former radio host, and party volunteers, who, he said, are making calls, knocking on doors, talking to groups, and dropping in on barber shops. How much knocking, talking and dropping in are going on in Detroit remains unclear. The state GOP will not share data on how many hands have been shaken and leaflets pressed into them through Bradley’s work. The party also won’t share how many black Republicans they believe already exist in Detroit. But they will say they are satisfied with the effort, and that African Americans are some proportion of the 2.5 million Michigan voters they have contacted this year by phone or face-to-face contact.

The success of the work won’t be known until after Election Day, which, Bradley and others say, is unlikely to be much of a needle-mover. They’ll be happy with a percentage point or two of improvement in state races, said Darren Littell, spokesman for the state party.

“We’re not going away,” Littell said. “The office will stay open after Nov. 5.”

It makes sense on paper

To Bradley, pitching the Republican Party in Detroit makes perfect sense. You want good public education? So does the GOP. You want a better Detroit? Hey, Gov. Snyder is in your corner. You believe in church and family? You’ve come to the right place.

And yet, election after election, Republican candidates are squashed like bugs in Detroit. Sometimes only in Detroit; 2010 Democratic gubernatorial candidate Virg Bernero collected more than 93 percent of the city’s ballots in the course of being routed by Gov. Rick Snyder elsewhere the state, losing by 18 points. But Republicans never do well in Detroit, and, in general, among people of color. Mitt Romney received only 6 percent of the African-American vote in Detroit in 2012.

In a report prepared by national Republicans for their peers soon after that defeat, the party took note of the demographic bomb ticking in its base: “In 1980, exit polls tell us that the electorate was 88 percent white. In 2012, it was 72 percent white. ...If we want ethnic minority voters to support Republicans, we have to engage them and show our sincerity.”

Hence, Bradley, working out of the storefront near Seven Mile. It is one of two new offices in the country that the Republican National Committee has dedicated to the cause of selling the GOP to voters of color – the other is in Charlotte, N.C. – although Bradley says the effort is nationwide. The Detroit office also serves as a general campaign office for GOP candidates. Posters for U.S. Senate candidate Terri Lynn Land and others decorate the walls, giving the place a look of impermanence. But the work of making inroads in the city is serious, Bradley says:

“We’re stepping up in Detroit. It’s an opportunity to engage voters who haven’t heard from us in the past, who’ve been disconnected from the GOP because we haven’t been present.”

And so Bradley (who goes by @ConservativeBro on Twitter) said he is making himself present – at church groups, block clubs, high-school reunions, wherever he can pop in, shake some hands and spread the word that the Republican party is looking for votes in the black community.

He said the reaction is always polite and friendly, like from the men at Dixon’s. People listen, nod, smile. Sometimes they might pull him aside later for a tete-a-tete about business taxes. But he’s realistic. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and Detroit won’t have a significant Republican voting presence for...well, a while.

“You have to plant seeds,” Bradley said. “The only we can go is up. Build the relationships, build the trust.”

Jack Kemp revival

Bradley grew up just a couple blocks from the office where he now works. His Democratic parents sent him off to Michigan State University, where he fell under the sway of Jack Kemp, the New York Republican congressman and onetime cabinet member under George H.W. Bush. Kemp, who died in 2009, was white, but embraced minority outreach for the party.

“His vision for America, and his inclusiveness,” said Bradley. “He pushed me over the top.”

As it happens, Kemp had his own vision for cities like Detroit. Kemp, a star quarterback, was actually drafted by the Detroit Lions in 1957, but traded before the season started, and later starred in the American Football League. He represented the Buffalo, N.Y. area in Congress, where his enthusiasm for an economy built on deep tax cuts earned him influence in the Republican Party that continues to this day. Kemp’s foundation describes his philosophy as one of “principled pragmatism, friendly strife, empowering others and, especially, reaching out to those who had not yet attained the American Dream.” He championed “urban enterprise zones” for cities like Detroit, areas of tax-free development and profit-taking, to encourage reinvestment. It’s a theme that resonates powerfully with urban conservatives.

Seeking company

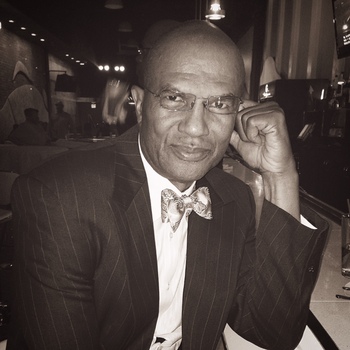

Being a black Republican, Bradley notes, makes one “a minority among a minority.” It requires a certain confidence in one’s own contrariness that you can see in others, as well. Ask Detroit lawyer Jerome Barney why he’s a Republican, and settle into your chair. This is going to take a while.

Barney comes from a family of African-American entrepreneurs, he says. Lower taxes and less government – traditional Republican platform planks – appeal to him. His family never wanted handouts, he said, only a level playing field. Their roots as Republicans go back to Dwight Eisenhower, when “the racists were Dixiecrats, and they were Democrats.”

But finally, there in his office, he will pull his phone out, flip through it and show you a photograph of the historical marker in Jackson, Mich., where the national Republican party was founded. A rock on the site carries this inscription:

Here, under the oaks,

July 6, 1854, was born

– the Republican Party –

Destined in the throes of civil strife to abolish slavery, vindicate democracy and perpetuate the union.

“That’s it, right there,” he said. Anti-slavery, pro-democracy and willing to fight for it. But that was the party 160 years ago. How does party loyalty play out in an era when a loud cohort of the party successfully kept the idea that Barack Obama’s birth certificate was fraudulent in the public eye for years?

You ignore those people, Barney said, and concentrate on relationships you have control over.

Barney, 65, has a resume that includes work with former Gov. John Engler, former Detroit Mayor Coleman Young and others that convinced him that moderation, and cooperation, is the key to advancement for both himself and his community.

“It’s important to be in the room to advocate for your culture and your constituency,” he said.

But he said he also believes that Detroit’s overwhelming one-party power imbalance does it no good, either. “We’re ignored by the Republicans, and taken for granted by the Democrats. It’s better to be in the room than taken for granted.”

Still, like Bradley, he’s realistic: “‘Republican’ is a cuss word in the black community.”

That’s echoed by Kerry Leon Jackson, a lawyer who now works in commercial real estate. Born and raised in a Democratic household, he, too, was converted to the red side by Kemp. Like Barney, he has little patience for the party’s tea-party wing, who he said are alienating independent voters who might otherwise be lured to the GOP.

“The ones making the news? The ones making the crazy comments about rape? I get the phone calls to defend this crazy fool and I can’t,” Jackson said. “The only way we’ll up the numbers and have a shot is, we have to be in the community, and support the things people care about.”

And what do African-American voters care about? The same thing others do, he said.

“The African Americans who moved to the suburbs, if they opened their minds, would know the Republicans really are on their side. We stand for good schools and safe streets.”

GOP effort questioned

Whether Bradley and other African-American Republicans are effectively delivering that message is unclear. His office granted only one request to cover its African-American community engagement events – the one at Dixon’s barber shop. And that was over in minutes.

Which leaves some political observers amused.

“(The Republicans) do this every so often,” observed Mark Grebner, president of Practical Political Consulting in Lansing, who works most often with Democrats. “It won’t work, but don’t let me stop anybody (from trying).” The numbers, he said, and the perceived injustices that Republicans heap on African Americans, are simply too overwhelming.

“Look at how (the GOP) treats Obama,” he said. “And the studies I’ve seen of black Republicans is at least half defect in any given election.”

That’s true, in at least one instance, of Barney and Jackson, who voted for Obama in 2008, they say for personal reasons – they both had lived in the same neighborhood in Chicago.

“I became a Colin Powell Republican, yes,” Barney said. But forging his own path has never bothered him. That’s why he’s a Republican in the first place.

A glimmer of promise

In the end, the best hope for Republicans may rest with folks like the occupant of another Detroit office, on Jefferson near downtown, where Thomas Adams, director of operations for the Rick Snyder campaign in Detroit, presides.

Adams, who is African American, is a big fan of Snyder, and is back for his second go-round running his Detroit office. Like Bradley, Adams touts the improvements to the city in the last four years – vigorous downtown development, a blossoming Belle Isle, better services, a planned new hockey arena.

“Rick Snyder made it very plain in his first election that he didn’t think he needed to win Detroit, but he wanted it,” Adams said. “His goal was to be governor of all the people. He has said whether you support me or not support me, I will still do everything I can to enhance the quality of life in Detroit.”

How will Adams be voting? Do you need to ask? For Rick Snyder, he said.

And does he consider himself a Republican? No, he said.

“I’m a Democrat.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

It isn’t the loneliest campaign office in Michigan. But Wayne Bradley knows he has a tough job ahead of him as he works out of this storefront on Detroit’s west side, trying to bring African Americans into the GOP tent. (Photo credit: Nancy Derringer)

It isn’t the loneliest campaign office in Michigan. But Wayne Bradley knows he has a tough job ahead of him as he works out of this storefront on Detroit’s west side, trying to bring African Americans into the GOP tent. (Photo credit: Nancy Derringer) Wayne Bradley gets a polite, if tepid, reception to his Republican campaign pitch at Dixon’s Barber Shop on Detroit’s west side. (photo credit Nancy Derringer)

Wayne Bradley gets a polite, if tepid, reception to his Republican campaign pitch at Dixon’s Barber Shop on Detroit’s west side. (photo credit Nancy Derringer) Republican Wayne Bradley plugs away at African-American engagement from a small storefront office on Livernois in Detroit. (photo credit Nancy Derringer)

Republican Wayne Bradley plugs away at African-American engagement from a small storefront office on Livernois in Detroit. (photo credit Nancy Derringer) Lawyer Jerome Barney acknowledges that being a Republican isn’t always easy in Detroit: “‘Republican’ is a cuss word in the black community.” (Courtesy photo)

Lawyer Jerome Barney acknowledges that being a Republican isn’t always easy in Detroit: “‘Republican’ is a cuss word in the black community.” (Courtesy photo) Thomas Adams is running Gov. Rick Snyder’s Detroit campaign office for a second time. (Courtesy photo)

Thomas Adams is running Gov. Rick Snyder’s Detroit campaign office for a second time. (Courtesy photo)