This law promised medical hope for dying patients. Was it a cruel deception?

The appeal to Michigan lawmakers was impassioned and powerful.

Terminally ill patients near the end of their lives. Conventional medical treatments failed. And now they wanted only a chance at experimental drugs not yet cleared by the government for the market.

But more than two years after Gov. Rick Snyder signed a drug-access measure known as Right to Try, it's hard to find a noticeable impact in Michigan – or anywhere else such laws have passed.

State and national experts interviewed for this report said they were not aware of a single case in which a severely ill Michigan resident has accessed experimental medication under the law.

The obstacle, experts say, is not the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the agency that approves experimental drug treatments. It’s pharmaceutical companies, which are reluctant to release unproven and potentially unsafe drugs to the public, and are not required to do so under Michigan’s law.

One critic of Right to Try said its apparent lack of impact was predictable.

“I think it’s because the legislators don’t understand what they are voting on,” said Arthur Caplan, professor of medical ethics at New York University's Langone Medical Center and a notable national critic of Right-to-Try laws.

“I see it as a combination of ignorance and feel-good legislation that doesn’t do what they said it would do.”

Caplan and other critics contend that Right to Try laws raise false hopes for sick patients by promising access to experimental drugs the law often can’t deliver, while posing unnecessary risks to patients that can outweigh a drug’s potential benefits.

Broad support, negligible results

Under Right to Try, terminally ill patients can seek access to drugs that have completed just the first of three phases of clinical trials performed by the FDA. Normally, a drug must go through all three phases before it’s prescribed, a process that can take a year or more, time terminally ill patients often do not have.

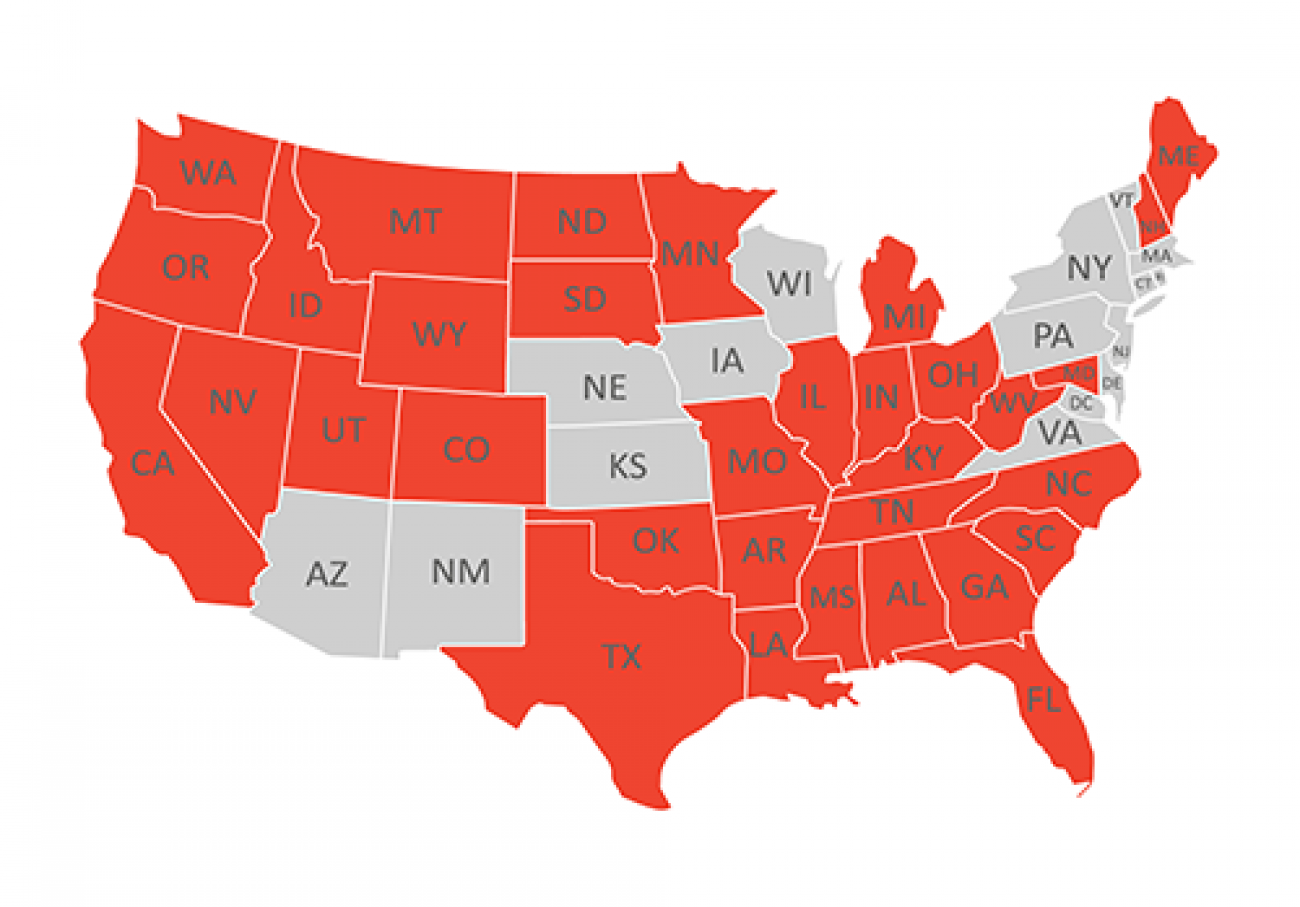

When Snyder signed Right to Try into law with near-unanimous legislative approval in October 2014, Michigan became the fourth state with such a measure. Today, 37 states now have some version of Right to Try, with several more considering it.

“We think the potential impact (to patients) is in the tens of thousands,” said Starlee Coleman, vice president of communications for the Arizona-based Goldwater Institute, a libertarian think tank that brought national exposure to the issue when it wrote the model for Right to Try laws now in place across much of the country.

“Forty thousand women a year are told by their doctor they are out of options for treating breast cancer,” Coleman said. “There are 22 drugs for breast cancer now in phase two or phase three trials. We can’t quantify how many breast cancer patients might be helped by drugs in the FDA pipeline, but we know that many thousands of patients would have the chance to try promising treatments that might work for them” if patients turning to experimental treatments were given early approval.

But Coleman conceded to Bridge Magazine she can't document that kind of impact.

“There isn't a database like that,” she said. “Anything we hear about is anecdotal. We don't have any way of giving you a comprehensive number.”

She said she is unaware of any Michigan patients accessing drugs through Right to Try.

A phantom solution?

Medical ethicist Caplan said he doesn't buy the dramatic claims for Right to Try. To the contrary, he and other critics assert it is a measure that at best does nothing ‒ and at worst could crack open the door to dangerous treatments and undermine the clinical trial system.

“It's the most empty piece of legislation you've ever seen,” Caplan said.

While Michigan's law allows pharmaceutical firms to give patients with advanced illnesses experimental drugs, it does not require that firms pay for them. It does not require health care plans to cover the drugs (Michigan’s law also shields doctors from the loss of their license for recommending experimental treatment).

Among what’s misleading, say medical experts, is the suggestion that states, through these laws, can somehow broaden patient access to experimental drugs.

“(T)he federal government, through the FDA, controls drug approval, and federal law trumps state law,” writes Dr. David Gorski, a cancer surgeon and researcher at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute in Detroit, and an editor at the Science-Based Medicine blog. “State right-to-try laws have no power over the FDA, and nothing states can do can compel the FDA to abide by their right-to-try laws.”

Caplan said the real barrier to terminal patients obtaining unapproved drugs isn't FDA bureaucracy. He said it's pharmaceutical companies – which are in many cases hesitant to risk bad publicity and the loss of millions of dollars in research investment if a patient dies using an experimental drug.

Drug manufacturers may also be reluctant to provide experimental therapies because of the potential cost, or because they don't want to be swamped by desperate patients when the firm only has a limited supply of a drug.

And nothing in Michigan's Right to Try law compels a pharmaceutical company to make a drug available.

Meanwhile, the FDA has its own – admittedly limited – channel for making unapproved drugs available to terminal patients.

The FDA grants more than 1,000 requests a year – and lately about 1,800 – for drugs still in clinical trials through the agency's “compassionate use” program, in place since 1987. It's difficult to say precisely how many patients gain access this way since some requests are for multiple patients.

According to FDA data, more than 99 percent of applications are approved in cases where it has determined the risk of treatment is outweighed by the potential benefit. That gives desperately ill patients access to drugs still in phase two or three of clinical trials even if the patients seeking the drugs are not part of the trial.

Better Access?

The American Society of Clinical Oncology supports a variety of measures to help terminal patients gain access to experimental treatments

- Require drug manufacturers to make information about their expanded access policies readily available to patients and doctors

- Support development of an online navigational portal to assist patients making requests for drugs to manufacturers

- Require drug manufacturers to list the anticipated length of time to respond to a request

The FDA in 2016 streamlined its application process to make it easier for patients to gain access to experimental drugs. In testimony to a U.S. Senate subcommittee, Peter Lurie, associate FDA commissioner, said emergency requests are “usually granted immediately” by phone with other requests usually processed in about four days.

Michigan cancer specialist Daniel Hayes said it’s the FDA’s compassionate use program that remains the best means to get reasonably safe, potentially life-saving experimental drugs in the hands of terminal patients.

Hayes is president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which in April issued a statement opposing Right to Try laws, saying they were “not an effective mechanism for improving access to investigational drugs.”

“We believe the Right to Try laws are well meaning but misguided,” said Hayes, clinical director of the Breast Oncology Program at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Hayes too said he was unaware of any Michigan patients who had sought access to treatment through Right to Try.

Little time to wait

Troy resident Terry Kalley has a different perspective on the issue, borne of personal experience.

In 2011, his wife, Arlene, faced the prospect she would lose access to the cancer drug Avastin after the FDA concluded it was ineffective in treating metastatic breast cancer. At the time, she had been fighting breast cancer for 30 years.

The FDA's decision on Avastin stirred up a national controversy, fueled by the fact the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, a nonprofit network of cancer treatment centers, voted 24-0 in support of the use of Avastin in concert with another drug for advanced breast cancer.

Kalley quit his job and formed the group Freedom of Access to Medicines to keep Avastin available and to argue for the right of patients to get access to experimental treatments.

In 2014, he testified before a state House committee in favor of Right to Try: “Denying a person the right to access drugs that might save their own life flies in the face of our due process rights embedded in the Constitution.”

Arlene Kalley died in August 2015.

“The principle is really simple,” Terry Kalley told Bridge Magazine.

“If you are facing death and you have few if any other options, who is to tell you as a patient you should not take a particular drug? Look, you say to the pharmaceutical company you have something that might work. If we can find something beneficial for both parties, I'd like to try it, thank you.”

Kalley was a key supporter of Michigan's Right to Try law, as he approached then-state Sen. John Pappageorge, R-Troy, about passing such a measure. Pappageorge was its primary Senate sponsor, clearing it through the Senate by a 31-2 vote. A similar measure passed the House 109-0.

Reached by Bridge, now-former Sen. Pappageorge said he still does not understand opposition to Right to Try.

“This is not ‘You must do this.’ It is your choice to try it. People say it could hurt someone who tries it. Don't you get it? They are going to die.”

A patient-centered movement

The push for swifter access to experimental drugs for the terminally ill gained steam with the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, as patients urgently sought treatments not yet approved by the FDA.

But Right to Try truly became a movement when the Goldwater Institute got behind it. The group argued that FDA bureaucrats were blocking the rights of terminal patients. Supporters invoked the 2013 film “Dallas Buyers Club,” which portrayed a Texas H.I.V. patient who smuggled treatment drugs from Mexico and distributed them to others with the disease because the medication wasn’t yet available in the U.S.

Right to Try appears to have the support of the Trump administration, as bills now in the U.S. House and Senate would prevent Washington from blocking state Right to Try laws and bar the FDA from considering medical outcomes for patients who met the standards for Right to Try treatment.

The Goldwater Institute most often points to Houston radiologist Ebrahim Delpassand as proof of Right to Try's impact, saying he has treated more than 100 cancer patients under the Right to Try law in Texas. Delpassand said he turned to the law to increase the number of patients he was treating using an experimental radioisotope therapy.

Goldwater Institute Vice President Coleman said there were two other patients who received treatment through Right to Try, but she was unable to provide names or any documentation of their cases.

But a researcher at NYU’s School of Medicine disputed the claims about Delpassand, asserting that the medication he used had already been approved for expanded access by the FDA.

“We do not accept this claim as evidence of one or more patients receiving otherwise unavailable drugs because of a Right to Try law,” said Lisa Kearns, senior research associate in the medical school's Division of Medical Ethics. “To the best of our knowledge, no patients have been helped by Right to Try laws.”

Beyond that dispute, one long-time pharmaceutical executive said he believes Right to Try has clear potential to harm patients and undercut the clinical trial system.

“You can't make a blanket statement that drugs are safe after phase one,” said Kenneth I. Moch, president and CEO of Pittsburgh-based Cognition Therapeutics, Inc.

Moch is a member of an NYU School of Medicine working group set up in 2014 to explore ethical issues related to patient access to exploratory drugs before they receive FDA approval.

Moch said it's one thing to administer a phase one drug to healthy patients in a (generally, small) study primarily geared to test a drug's side effects. It's quite another to give it to a seriously ill cancer patient who may be older and who may be taking other medications that could trigger harmful or fatal interactions with the experimental drug.

Moch noted that while the FDA reviews experimental drugs under its compassionate use program to determine – at the least – that the risk of side effects from a treatment is no greater than harm from the disease, Michigan’s law has no such provision.

“You could accelerate a side effect,” Moch said. “You could accelerate death. People shouldn't fool themselves. This will happen.”

CORRECTION: The original version of this article misidentified the working group on which Kenneth I. Moch sits. He is a member of the NYU School of Medicine Division of Medical Ethics Working Group on Compassionate Use and Pre-Approval Access. This working group has no affiliation with Johnson & Johnson or its affiliates.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!