Michigan redistricting panel’s maps spark racial backlash, fairness questions

Oct. 28: Michigan redistricting may help Democrats. But will it hurt Black voters

Oct. 19: Michigan’s redistricting group’s maps harm Black voters, research finds

LANSING — Michigan’s first attempt at having citizens draw the state’s political districts was supposed to safeguard — if not enhance — the voices of minority voters.

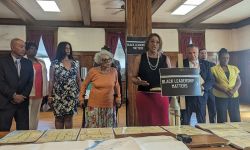

Instead, some of the loudest complaints about 10 draft maps proposed on Oct. 11 by the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission are from African American leaders who say proposed districts will marginalize voters.

Michigan now has 17 majority-Black districts — two in Congress, five in the state Senate and 10 in the state House.

Related:

- Republicans have edge, but Michigan House drafts include plenty of surprises

- Michigan redistricting drafts could make state Senate a toss-up

- Michigan congressional redistricting drafts are done. Few incumbents are safe

Proposed maps would have only one district whose voting age population is more than 50 percent African-American, while there are four whose total population is over 50 percent Black.

New rules push districts into odd shapes

The citizens redistricting commission has emphasized preserving “communities of interest” more than county boundaries in its push to create congressional, senate and house districts.

That’s led to districts in metro Detroit that stretch from the heart of the nation’s largest majority-black city up into the suburbs of Oakland and Macomb counties. The maps give Democrats a better chance at winning more races but minorities may also have fewer seats if the maps are adopted.

(Left: Current House) (Right: Proposed House (‘Pine’)

Currently Detroit touches 10 House districts; all three proposed maps have portions of the city in 17 districts, several of which are barely a mile wide and connect some of the poorest neighborhoods of Detroit with some of the richest communities in Oakland County.

(Left: Current Senate) (Right: Proposed Senate (‘Cherry’)

Currently, Detroit is represented by five Senate districts. The proposed maps would increase that total to eight, with the city sharing senators with suburban communities in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties. No senate district currently leaves Wayne County.

Either way, African-American leaders say there should be far more, especially since the commission spent two months drawing maps and gathering public input.

“They went on a listening tour prior to them putting pen to paper and drawing up the maps,” said Jonathan Kinloch, chair of the 13th Congressional District Democratic Party Committee and a Wayne County commissioner.

“But, obviously, as they went around the state, as they went through the Black communities, and received testimony around the state from Black voters, they honestly did not listen to us.”

Other minority groups, including the Bangladeshi and Hispanic communities in the Detroit area, are happier with the maps because they include districts that would make them a sizable bloc or the majority.

The commission was created by voters in 2018 after decades in which the party in power in Lansing drew maps every 10 years. That led to districts that gave the Republicans firm control of the Legislature, even though the state overall leans Democratic.

The redistricting commission drew districts that tried to take into consideration seven criteria, including the Voting Rights Act, “communities of interest” or like-minded groups, and political fairness.

They put less emphasis on maintaining county boundaries, which has created many odd-looking districts, especially in Detroit, the nation’s largest majority-Black city.

Of the state’s current districts, none of the 10 in the state House in Detroit touch neighboring counties. But three proposed maps have 10 districts that do so, running like alleys from Detroit as far north as Bloomfield Hills.

In all, 10 different districts would span the 17 miles of Detroit’s northern border, Eight Mile Road, up from four now.

“Equality does not mean equity,” said Yvonne White, the president of the Michigan NAACP, earlier this week. “In addition to the one person, one vote doctrine, all redistricting plans must also comply with the requirements of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.”

The redistricting commission followed the advice of attorney Bruce Adelson, who it hired to maintain voting rights.

He argues that previous districts, drawn by partisans, diluted the voices of minorities by “packing” them in racially gerrymandered districts. Three state House districts are now composed of 90 percent Black voters, including one represented by Stephanie Young, D-Detroit, that is 97 percent Black.

Adelson has contended districts don’t have to be more than 50 percent minority to ensure they have a strong vote. He has suggested a lower threshold.

“The U.S. Supreme Court has been clear that if you put additional minority voters into a district beyond what is needed to elect candidates of choice, that's an issue,” Adelson told commissioners earlier this month.

Edward Woods III, the commission’s communications and outreach director, told Bridge Michigan the commission is following the law.

He said there is no evidence that the draft maps violate the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the federal law that ensures minority voters aren’t discriminated against in voting.

“At this time, our proposed maps passed a rigorous analysis to ensure compliance with the Voting Rights Act and eliminated the concern of gerrymandering through packing,” Woods told Bridge Michigan in an email.

“Although there is a court of public opinion, the Michigan Supreme Court holds us accountable to the seven ranked redistricting criteria to draw fair maps through public engagement. That’s what voters wanted when they empowered citizens to handle the redistricting process.”

Woods said those with concerns should direct them to the commission via its website or during public hearings, which begin Oct. 20 in Detroit. Hearings will follow in Lansing (Oct. 21), Grand Rapids (Oct. 22), Gaylord (Oct. 25), and Flint (Oct. 26).

How much representation?

Districts are redrawn every 10 years after the census, and Detroit was bound to lose clout because its population fell by nearly 75,000 residents to 653,711.

But advocates like Kinloch and Sen. Adam Hollier, D-Detroit, say stretching districts into neighboring communities dilutes the voice of the city because candidates would need support from city and suburban voters to win.

“They drew the City of Detroit into districts that Detroiters will not win, and Black people will not win because a majority of the voter base are in suburban communities particularly in primaries where Democratic races are decided,” Hollier said.

Hollier’s district would drastically change. Currently, it includes the North End neighborhood, Harper Woods, all of the Grosse Pointes, Highland Park and Hamtramck.

Under the drafts, his district would stretch all the way to Madison Heights in Oakland County and pick up Greektown, the East Village, Hazel Park and Hamtramck.

Representation is important because, while African-Americans comprise 13.5 of Michigan’s population, they are historically underrepresented in Congress and the Legislature.

Eleven percent of the 162 congressional and state Legislature districts, 19 in all, are majority Black.

Hollier and others want the commission to take voting age — not just population — of voters into consideration.

In one proposed House district that would stretch from the Belmont neighborhood in northwest Detroit to Farmington, the district’s total population is 48 percent Black, 38 percent white and 12 percent Asian American.

The district, though, is 47 percent Black and 40 percent white when only voting age is considered.

Jeff Timmer, a longtime Republican strategist, said complaints from Hollier and others ring hollow.

Timmer helped draw maps in 2010 that courts determined were gerrymandered and said Black voters have long been “packed” into districts — often at the request of Black incumbents who traded support for safer districts.

“If people want to get parochial like that in trying to advantage themselves under the guise of the Voting Rights Act, all they're doing is helping the Republicans,” Timmer said.

He added the commission should further unpack districts.

“The needle is moving in the right direction, but the 10 maps that the commission has come out with this week show that there's still a long way to go,” Timer said.

“And I would say that they haven't done enough to satisfy the Voting Rights Act.”

Joy in Banglatown

Other groups are far happier with maps they say finally acknowledged them and kept their communities intact.

For months, members of the Bangladeshi community— most residents of Hamtramck and Banglatown — appeared before the commission to not split them when they drew districts.

About half the 5,000 residents of Banglatown, a community between Hamtramck and Detroit, are Bangladeshi-American, which activists say is one of the highest populations in the nation.

“This is a community that has stabilized the north Detroit area,” Kamal Rahman, a resident of the Hamtramck, told Bridge Michigan.

“When other areas … (were) on heavy decline in the ‘80s and ‘90s … (the) Bangladeshi community stabilized it, started buying homes and bringing their family here for a new life,” Rahman said.

“However, we're not getting the attention that we deserve.”

Rahman said he is relatively happy with the draft maps put out by the commission.

Under the proposed congressional and Senate maps, the community remains together. But the House district leaves out about four blocks.

Rebeka Islam, the executive director of Asian and Pacific Islander American Vote Michigan, told Bridge Michigan community members will show up at the meetings to ensure the commission fixes that.

She added the latest proposals are better than what the commission initially drew.

“It shows that public comments are working and they're listening to us,” Islam said. “We shouldn't have to keep going back, you know, that is the problem that we shouldn't have to keep going back. But it showed that public comments are working.”

Other Bangladeshi activists have said they would like to see a district that includes the city of Warren, and they said they’ll ask the commission to reconsider it.

The Hispanic community in Detroit, meanwhile, is also celebrating because one district, along Southwest Detroit and River Rouge would be 55 percent Hispanic.

Mary Carmen Muñoz, the executive director of Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development, said it is “incredible” to have a district like that.

“This map could have a significant impact on the lives of the Latinos in southwest Detroit,” Muñoz told Bridge Michigan. “It could affect— it will affect — resources, it will affect education.”

Oscar Castañeda, a community organizing and advocacy coordinator at the Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, agreed.

“Everybody knows that minorities are not really good at turning at the voting booths on Election Day, and when you talk to the community one of the main reasons is that they don't feel represented,” Castañeda said. “Being able to say that there is a district where potentially we might have a Hispanic who really cares for the Hispanics — this is huge.”

— Bridge Michigan reporter Mike Wilkinson contributed

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!