Missing in action: Michigan's primary voters

While Michigan's general election in November will claim its share of headlines, it’s the predictably overlooked Aug. 2 primary next Tuesday that’s as likely to shape state politics for years to come.

And yet if the past is prologue, just 1-in-5 registered voters will even bother to show up. In at least a couple a dozen open state House primaries - where districts are strongly tilted toward one party or the other - this sliver of voters will in all likelihood determine the winner of the general election as well.

“I don't see any reason to expect any big difference this time around,” said Matt Grossmann, director of Michigan State University's Institute for Public Policy and Social Research.

“It's not just that you are giving up your chance to participate in the primary. It's a civic responsibility. If you give that up, you are making a choice in how involved you are going to be in your community and your state.”

This voter disappearing act has been playing for decades.

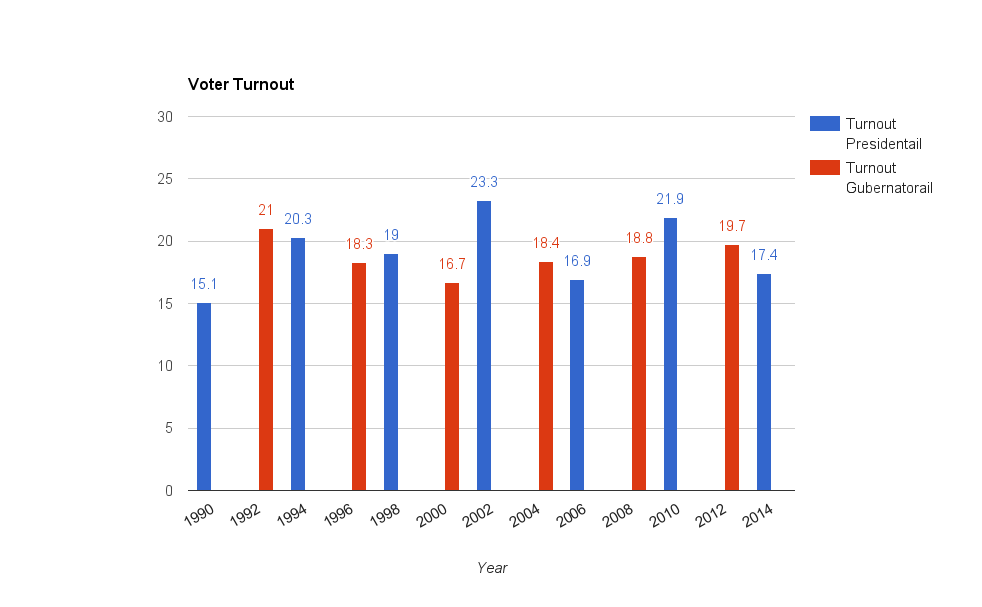

e: Michigan SOS)In 2012, the last presidential cycle, 19.7 percent of registered voters in Michigan turned out in the primary, which was actually better than 2008, when 18.8 percent somehow found their way to a voting booth. Primary turnout dipped as low as 15.1 percent statewide in 1990, a gubernatorial election cycle.

It's even worse in some locales: In 2006, 6.6 percent turned out for the primary in the Upper Peninsula's Dickinson County.

In a sense, Grossmann said, the primary no-shows are ceding the right to select winners to the voter cohort most likely to turn up at the polls.

According to the Pew Research Center those voters tend to be elderly, more affluent, better educated and more likely to attend church regularly.

This year, control of the 110-seat state House will be determined by outcome of the Nov. 8 election, in which the Democrats are given an outside chance to wrest control from the GOP. But either way, the primary results will go a long way in defining the character and makeup of both parties.

The seats of 41 incumbent state representatives are open, by and large due to term limits. Thanks to political gerrymandering, at least a couple dozen of these districts tilt decisively toward one party or the other.

Of those seats, 13 rate at least 60 percent toward one party partisan and 27 at least 55 percent toward one party, partisan, according to Inside Michigan Politics, a Lansing political newsletter. Its calculations are based on votes for the state Board of Education – considered a neutral barometer of party affiliation - the past four election cycles.

The primary winners of the dominant party in these races will be odds-on favorites in the fall. Put another way, the primary is the election.

And judging by plenty of political resumes since term limits passed in 1992, some of these winners will go on to serve the allowed maximum 14 years in the Legislature – six years in the House, plus another eight years in the state Senate.

The general rule of thumb in contested open primaries is this: The more heavily tilted toward one party partisan a district, the more candidates from the dominant party will queue up to run. A sampling:

House 86th near Grand Rapids - Republican

East of Grand Rapids in the rural 86th House District, five GOP candidates are running to replace Lisa Posthumus Lyons, who is term limited and on the ballot for Kent County clerk. The field includes lawyer and mediator Katherine Henry, lawyer Jeff Johnson, Marine Corps veteran Thomas Albert, Bartholomew James, once listed as a Libertarian candidate for president, and Matthew VanderWerff, a farmer and accountant.

They are competing in one of the most conservative House districts in the state – 68 percent Republican, according to Inside Michigan Politics.

That makes the GOP primary winner strongly favored in the fall, even though Democrat Lynn Mason – who raised more than $100,000 in 2014 – is running again. Mason got 34 percent of the vote last time around.

House 15th Dearborn - Democratic

In the Dearborn-based 15th House District near Detroit, six Democrats are jostling for the chance to succeed outgoing incumbent George Darany. It's an intriguing race, in part because Dearborn holds the highest concentration portion of Arab Americans of any city in the nation.

Darany has given his blessing to Dearborn Board of Education member Roxanne McDonald. That endorsement came on the heels of Wayne County Executive Warren Evans' backing of professional health adviser Abdullah Hammoud of Dearborn, the son of Lebanese immigrants.

Earlier this year, Hammoud reported receiving a hate-mail message including the words “No More Arabs” and “Go Back to Lebanon.”

The Democratic field also includes business owner Norman Alsahoury, former Dearborn School board member Alex Shami, U.S. Navy veteran Brian Stone and Dearborn Public Schools liaison Jacklin Zeidan.

Three Republicans have filed as well, construction worker Terrance Guido Gerin, chiropractor Richard Johnson and substitute teacher Paul Sophiea.

Given that the district is rated 61 percent Democratic by Inside Michigan Politics, the Democratic primary victor will have a clear advantage in the fall.

U.S. House 1st, Northern Michigan - Republican

This closely watched congressional race may hold more possibilities for November drama.

In the sprawling 1st U.S. House district of northern Michigan and the Upper Peninsula, three GOP candidates are fighting to succeed outgoing Congressman Dan Benishek, R-Crystal Falls.

They include state Sen. Tom Casperson of Escanaba, former state Sen. Jason Allen of Traverse City and Jack Bergman, a retired Lt. General from Watersmeet in the U.P. In the Democratic primary, former Michigan Democratic Party Chair Lon Johnson of Kalkaska faces former Kalkaska County Sheriff Jerry Cannon, who ran against Benishek in 2014.

The district rates a bit closer than many of the state races, at 54 percent Republican, according to Inside Michigan Politics. Democrats like to think they have a chance to win the seat, given that Democrat Bart Stupak served in the 1st from 1993 to 2011.

Senate 4th - Democratic tilt

In the Detroit-based 4th Senate District, nine Democrats are on the ballot to complete the term of replace former Sen. Virgil Smith, jailed in March for 10 months for shooting at his ex-wife’s Mercedes Benz. The district is rated 83 percent Democratic by Inside Michigan Politics – the most partisan Senate seat in the state and the only one up for grabs this year.

Best known in the bunch are Ian Conyers, great-nephew of longtime U.S. Rep. John Conyers Jr., and former state Rep. Fred Durhal Jr. The field also includes three candidates who lost bids for Detroit House seats in 2014, James Cole Jr., Carron Pinkins and Vanessa Simpson Olive. Republican Keith Franklin of Detroit is unopposed in the GOP primary.

The winner of the general election will serve the remainder of Smith's term, which runs through 2018.

Given the makeup of the district, said Susan Demas of Inside Michigan Politics, the Democratic winner would have to run a campaign unprecedented in its awfulness all but have to commit murder in order to lose the general election.

“It's the old metaphor about being caught with a dead girl or a live boy,” Demas said, adding that it is “virtually impossible” for a Republican to win this district. “There's just not enough people on the other side of aisle to overcome that.”

Grossmann of the Institute for Public Policy said voters who don’t show at primaries tend to know less about politics and state government than those who vote. They are less likely to know the names on the primary ballot, hence more likely to stay home.

Evidence shows there are plenty of voters without a keen knowledge of Michigan elections or politics. .

Grossmann cited an institute survey of state residents conducted in April which showed only 55 percent could identify the GOP as the party that controls the state Senate – not much better than guessing. Fewer than half of the respondents know that state legislators are subject to term limits. And more than 1-in-4 could identify Debbie Stabenow as one of the state’s two U.S. senators.

“It's not necessarily good to have someone vote for the only name they've ever heard of,” he said.

Correction: The original version of this article misspelled the name and military rank of GOP congressional candidate Jack Bergman. He is a retired Marine Corps Lt. General. The original article also misspelled the name of Matt Grossmann.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

If past is prologue, 4-in-5 Michigan voters will stay home for the Aug. 2 primary election. (photo courtesy of MLive)

If past is prologue, 4-in-5 Michigan voters will stay home for the Aug. 2 primary election. (photo courtesy of MLive) HOW LOW CAN YOU GO? Over the past decades, fewer than a fifth of Michigan registered voters have turned out for most statewide primaries (sourc

HOW LOW CAN YOU GO? Over the past decades, fewer than a fifth of Michigan registered voters have turned out for most statewide primaries (sourc Grossmann

Grossmann