Race looms large as redistricting process begins in Michigan

SALT LAKE CITY — As states nationwide begin drawing new political boundaries, advocacy groups are girding for a fight to preserve districts designed to ensure racial minorities have a voice in Congress.

So-called majority-minority districts were created by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and have been under attack since. Now, advocacy groups are promising lawsuits if state legislatures or independent commissions dismantle the districts or ignore potential new ones.

“I urge you not to take that gamble, because the resources to bring these (legal) cases have increased over the years,” Thomas Saenz, the president of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), warned a group of more than 300 officials involved in redistricting last week at a gathering in Utah.

Related:

- Michigan Supreme Court won’t delay redistricting map deadline

- Michigan’s redistricting commission sought opinions. It got plenty.

- As Michigan begins redistricting, ‘communities of interest’ take center stage

- Census counts mean Michigan, Great Lakes states to lose power in Congress

Race was a key topic during the redistricting seminar sponsored by the National Conference of State Legislatures, as lawmakers grappled with how best to comply with sometimes conflicting laws that mandate equal representation but also are designed to ensure minority voices aren’t diluted.

Majority-minority districts are ones where a minority group makes up at least 50 percent of the population, increasing the likelihood a candidate of their preference will be elected. The districts were created by a law signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to guarantee voting rights of minorities, particularly in the South.

Nationwide, there are 122 such districts in the nation, including two in Michigan, representing about 28 percent of the 435 districts in the U.S. House.

As the U.S. Census prepares next month to release population counts that will form the basis for redistricting, advocates are debating how best to draw the majority-minority districts.

Michigan is about 26 percent nonwhite, according to Census estimates. The majority live in southeast Michigan, which is now represented by seven mostly Democratic-leaning congressional districts.

A large number of the people of color in that region, though, are concentrated into two majority-minority congressional districts — the 13th and 14th.

More than 65 percent of voters are people of color in the 13th district, represented by Rashida Tlaib, D-Detroit, and 14th, represented by Brenda Lawrence, D-Southfield.

Experts say that’s a phenomenon known in political circles as “packing” that can dilute the influence of minorities.

“Very frequently, what they end up getting is less representation than they would have if you didn't pack them in such a way,” said Jon Eguia, an economics professor and expert on redistricting at Michigan State University.

“You lose out all those voters with having to form coalitions with white voters or majority voters who have the same preferences as the minority wants,” Eguia said.

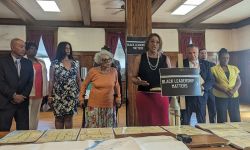

Racial representation is one big issue facing the Michigan Independent Citizens Commission, a bipartisan, 13-member citizen group created by voters in 2018. For years in Michigan, the party in power in Lansing, had created the districts every 10 years, an arrangement that led to some of the worst gerrymandering in the country.

But the challenge will be exacerbated because the latest U.S. Census population counts show Michigan’s population didn’t grow as much as other states during the last decade. This means Michigan will lose a congressional seat, going to 13 from 14, starting next year.

Kathryn Sadasivan, a redistricting attorney at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, told Bridge Michigan that losing a seat doesn’t mean the state can lose both majority-minority districts.

“That could never happen,” Sadasivan said, adding that the percentage of minority voters in one district should be closer to 51 percent than 60 percent to 70 percent.

She said her group “would most likely consider litigation” if Michigan or other states that lost representation tried to eliminate a majority-minority district.

One initial step for Michigan’s redistricting panel will be to identify whether communities of minority populations share political preferences before placing them in one district, Yurij Rudensky, a redistricting attorney at the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice in New York, told Bridge Michigan.

If the community seems to band together, the commission will then have to consider whether the white population in the region — or the majority— votes opposite to the minority population.

“If there is a candidate that is really backed by the black community, that draws their political power from the black community, are white folks voting against that candidate? Does that happen over and over again?” Rudensky said. “If you can demonstrate that, then you have a claim for a district to be drawn that has the protections of the Voting Rights Act.”

Katherine McKnight, a Washington, D.C.-based attorney who has litigated on behalf of politicians in redistricting cases, told those in attendance at the Salt Lake City redistricting meeting that in order to survive a lawsuit, redistricting panels need to be able to justify the new maps.

“The record you develop matters, it matters for every single district, and you're going to want to have that at the end of the redistricting process to make sure that you can support why you drew districts the way you drew them,” McKnight said.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!