What Flint lost

About a year ago, Victoria Marx lost her balance standing on a ladder while working at Home Depot. A couple of times. It was around that period that she noticed her right hand had started to quiver.

Last summer, Marx, 60, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, a chronic movement disorder that can result from a mix of genetic and environmental factors. A few months later, Gov. Rick Snyder appeared on television to apologize to the people of Flint, confirming they were exposed to high levels of lead after the city began taking its drinking water from the Flint River in 2014.

A test in Marx’s bungalow last month showed her water is still unsafe to drink. It was the lead in that water that damaged her nervous system. Marx cannot prove it, but that is what she believes.

She no longer, however, believes what the governor has to say.

“This is something I have to live with for the rest of my life,” said Marx, who walks with a limp now. “Things would’ve been fine if Snyder’s emergency manager hadn’t switched us over to the Flint River.”

To be a resident in Flint these days is to thrum with a mistrust for government. Coping for months with no fix, enduring a mix of bad information and too little communication, residents interviewed in recent weeks say their faith in all levels of government has been shattered, replaced by suspicion and, at times, paranoia as the same government agencies implicated in the lead crisis are now in charge of the recovery effort.

Some residents say they don’t trust the water filters distributed at fire stations because of questions about high lead levels. Others balk at accepting donated jugs of water for cooking and bathing because some containers had no labels. A few won’t accept certain brands of free bottled water due to E.Coli contamination they heard about on Facebook. Still others reject the accuracy of blood and residential water tests conducted by government workers. Another blames the lead for the deaths of her two German shepherds.

This visceral mistrust has only strengthened with the revelation that county, state and federal health officials dithered internally for most of 2015 before alerting the public that the water may have also contributed to nine area deaths from Legionnaire’s disease.

People here say that, months after lead contamination was finally confirmed, they still aren’t getting answers as to why some residents still get rashes, or if their daily lives will return to normal by next year, the year after that, or ever.

At a recent NAACP meeting one resident referenced law enforcement killings of unarmed African Americans nationwide and voiced fear of National Guard workers distributing water in Flint, saying “If I open my door when they come, and take out my cell phone, they might shoot me because they think it’s a gun.”

Echoes of a dark chapter

The people of Flint speak of the cascading series of government failures in the language of betrayal. For many residents, a majority African American, the steady drip of disclosures echoes the most infamous chapter in the history of public U.S. health, prompting cries of, “remember Tuskegee.”

On Feb. 1, pastors from Flint and Detroit held a townhall meeting that included rap and business icon Russell Simmons and attorney Phaedra Parks, a cast member on the cable show, “The Real Housewives of Atlanta.”

Hundreds of people showed up. Ministers preached, local leaders spoke.

Several times speakers mentioned the Tuskegee experiment, the 40-year, federally funded experiment on 600 uneducated black men in Alabama, who were told by government doctors they were being treated for “bad blood.” In fact, most of the men had syphilis and were unwittingly being studied to see how the disease would affect their bodies if left untreated, even after a treatment (penicillin) became available. Dozens died.

As it happens, one objective of the Flint town hall was to introduce residents to doctors and lawyers they were told they could trust to address their health and legal problems, instead of having to rely on government agencies.

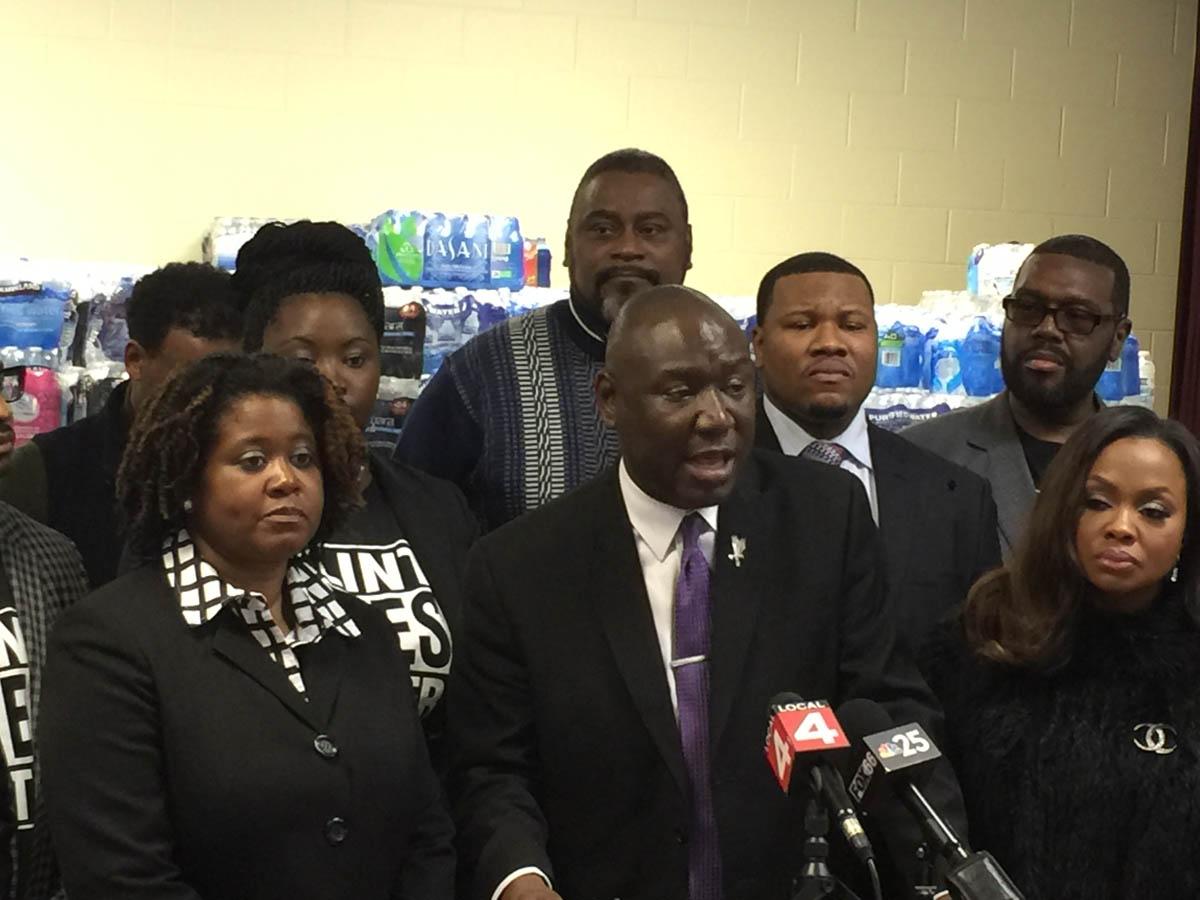

Benjamin Crump, civil rights lawyer and president of the National Bar Association, a predominantly African-American group, told the crowd that while they should get water and blood tested for free with local and state agencies, they should share and compare those results with tests conducted by their own lawyers and family doctors.

“How can the person who caused me pain be trusted to test...the level of my pain?” Crump asked of government officials. “This begs the question of independent testing.”

Frances Gilcreast, president of the Flint Branch NAACP, wrote an open letter to the city officials and Gov. Rick Snyder in February 2015, chastising the government for putting cost savings above water safety. Her sentiments echo through Flint a year later.

“If this were Grand Blanc, or Oakland County,” she wrote, “something would have been done immediately.”

Questions and doubts

Two blood testing sites that screened children for lead exposure over the past few weeks offered a festive atmosphere. Someone in a colorful monster costume danced the “Nae-Nae” with children. Face painters, snacks and balloon animals kept kids busy while parents poured over health questionnaires.

Parents asked about their children’s reaction to Flint’s water struggled to keep their emotions in check. Shavon Hamilton took deep breaths and looked off into the crowd, eyebrows furrowed. She had bottle-fed her infant daughter with tap water in 2014.

Kiara Settle let the tears well up. Her two-year-old son was tested once during a hospital visit and showed a lead level of 5.4 micrograms lead per deciliter of blood, indicating lead exposure. Her family had used the tap water during the first year after the switch to Flint river water.

“My baby was born in 2013,” said, Settle, 24. “They didn’t even give my baby a chance from the jump. I don’t care what they say about anything anymore. I’m trying to move.”

Residents said they want to trust results from the free water testing now being conducted by the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, but said the results can be confusing.

And, any way, they haven’t forgotten that MDEQ is the same agency that failed to correctly interpret the federal regulations on how to properly monitor and respond to the possibility of lead contamination in the water.

Kathleen Fridline was puzzled by the letter MDEQ sent to her elderly mother’s house. It said that her mom’s residential water test conducted in January showed a lead contamination level of 78 parts per billion. The “action” level is 15 ppb, the document stated.

But as she noted, the letter does not list the actions to take, other than to call the local health department with questions.

“What do we do now? Who do we wait to hear from? The city? DEQ? How do we address this,” Fridline wondered aloud while reading the results in her mother’s living room recently.

“I’d like to say I’m angry, but I’m just not an angry person. I’m concerned.”

Filters, bottled water questioned

Sometimes the information isn’t so much vague as contradictory, in the minds of some residents.

They note that local, state and federal officials have encouraged residents to use water filters, saying the filters will remove lead. But then they heard that EPA experts worried that the filters may not work if the lead coursing through a home’s pipes is higher than the filters can handle. Pregnant women and small children should use bottled water, the EPA said recently.

That’s the kind of contradictory information that fades residents’ trust.

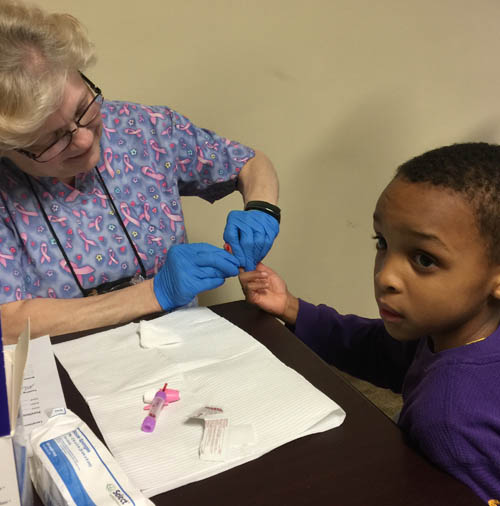

“I don’t know what to believe,” said JaMise Wash-Lang who took her son, JaCarie, to Carriage Town Ministries in Flint to have his blood tested this month.

His teachers say the 5-year-old has not been behaving like himself; he’s been more hyperactive. JaCarie has a mild rash that won’t go away. The family has been using bottled water for months, but bathed the boy in the tap water before a water emergency was declared in January.

Wash-Lang says she became anxious after a Facebook post went viral showing a woman, supposedly in Flint, testing several brands of bottled water and getting high lead content readings.

She knows how conspiracy theories about tainted bottled water and an uncaring government sound. Paranoid. Crazy, even.

Until it’s your water. Your child.

“My main concern is the inconsistency of information, what to do, where to get help.” She hadn’t had her residential water tested, but was taken aback by the water sample containers distributed along with free bottled water at the fire departments. A questionnaire is attached to the plastic bottle with a rubber band.

“A rubber band?,” she said. “What if the rubber band comes off? How is that saying that they value the accuracy of the test?”

Shavon Hamilton wants to avoid confusing information about filters and bottled water altogether. She said she is considering buying a reverse osmosis system to filter impurities including lead from water at the point of entry into her house. The system Hamilton wants could cost more than $3,000, or about $70 per month if she chooses a payment plan.

“It’s going to be another bill I really don’t need. But I’m doing it. I’m really scared,” she said. “I don’t feel like a good mother because I’m just now doing this.”

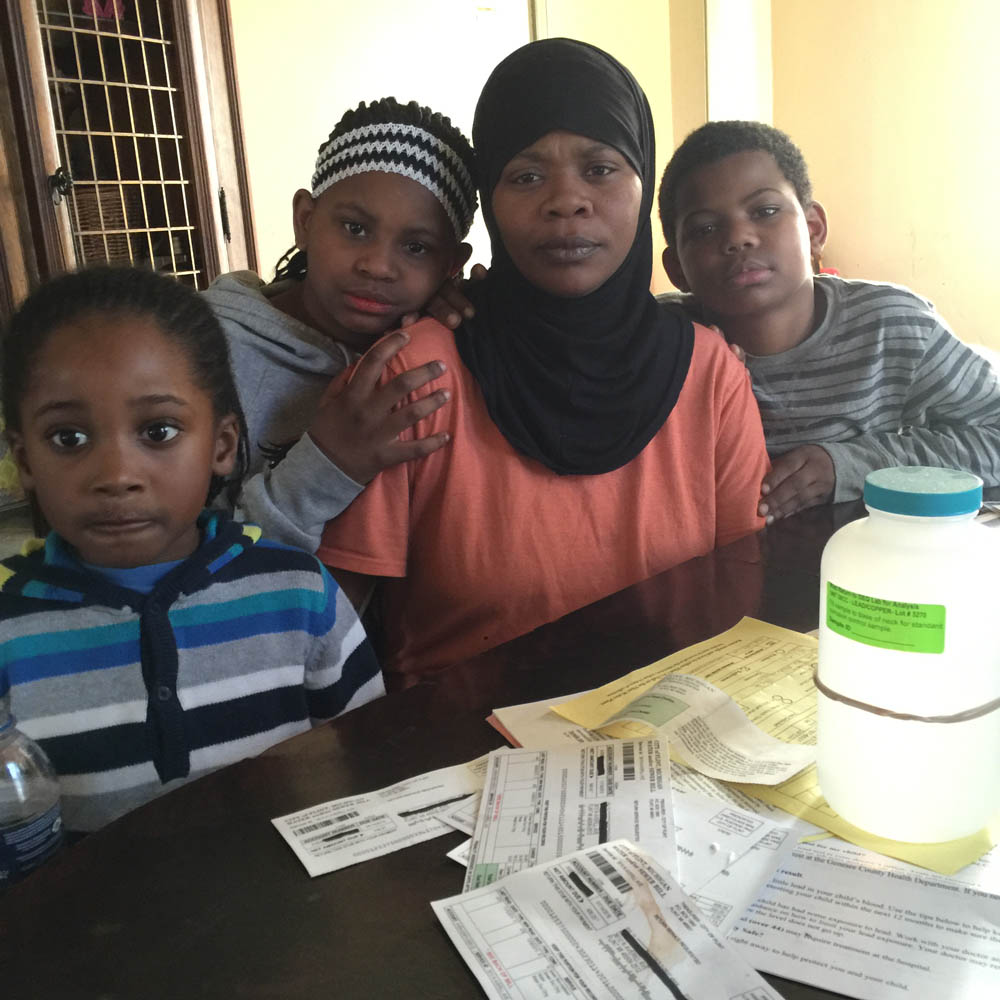

Mary Smith lost her last shred of trust in city officials when she arrived home from dropping off her kids at school on a recent Thursday to find the water department shutting off her water. This was no ordinary shut off – workers drove up in a backhoe and dug several feet into the ground to reach the city pipe line.

At first, she thought, “They can keep their poison water.” Then, she thought about her three children and nephew who live in the house. How would they flush the toilet?

The city said that it hasn’t shut off any customer’s water for nonpayment since August. City officials said Smith’s water was shut off because she didn’t file documents to put the water bill in her name when she started the process to buy the house from the city in November.

The city’s actions infuriated Smith, who said she wondered why the city was taking time to shut off her water on what she considers a technicality than devoting all of its time to making drinking water safe.

“This is the same government that told us for a year and half that we could drink the water. Nobody trusts the government anymore, especially not after all this,” Smith said. “It’s going to be hard to get the people’s trust back.”

Bridge computer-assisted reporting specialist Mike Wilkinson contributed to this report.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Many residents in Flint say the water crisis has left them with little trust for government officials. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey)

Many residents in Flint say the water crisis has left them with little trust for government officials. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey) JaMise Wash-Lang of Flint, took her son JaCarie, 5, to get a blood test last week. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey)

JaMise Wash-Lang of Flint, took her son JaCarie, 5, to get a blood test last week. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey) Civil Rights attorney Benjamin Crump is flanked by attorney and TV reality show star Phaedra Parks at a Flint press conference. Crump said residents should get lead testing independent of government testing. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey)

Civil Rights attorney Benjamin Crump is flanked by attorney and TV reality show star Phaedra Parks at a Flint press conference. Crump said residents should get lead testing independent of government testing. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey) Mary Smith, 34, with two of her three children and her nephew. (L-R) Khamarri Key, 4, Kayla Dantzler, 9 and Kyrin Dantzler, 10. The city shut off water service to their home on Jan. 28. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey)

Mary Smith, 34, with two of her three children and her nephew. (L-R) Khamarri Key, 4, Kayla Dantzler, 9 and Kyrin Dantzler, 10. The city shut off water service to their home on Jan. 28. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey) Curtis West, 57, and his daughter, Brooklyn Pratcher, 7, get two cases of free bottled water at a fire station. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey)

Curtis West, 57, and his daughter, Brooklyn Pratcher, 7, get two cases of free bottled water at a fire station. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey) German shepherds Soldier and Kizzie died within a month of each other last fall before the lead contamination was publicly confirmed in Flint’s drinking water. Their owner, Sonja Lee, suspects lead poisoning. The water in her home tested at 68 parts per billion, more than four times the action level of 15 ppb (Courtesy photo)

German shepherds Soldier and Kizzie died within a month of each other last fall before the lead contamination was publicly confirmed in Flint’s drinking water. Their owner, Sonja Lee, suspects lead poisoning. The water in her home tested at 68 parts per billion, more than four times the action level of 15 ppb (Courtesy photo) City workers had to access underground pipes to shut off water service at the Flint home of Mary Smith in January. City officials said they took the action because Smith had not yet switched the water account into her name from the previous owner. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey)

City workers had to access underground pipes to shut off water service at the Flint home of Mary Smith in January. City officials said they took the action because Smith had not yet switched the water account into her name from the previous owner. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey)