The fish that got away

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers says it has spent $110 million on electric barriers in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal that were supposed to keep Asian carp from swimming upstream to the Great Lakes.

It didn’t work in the initial testing phase in 2000. It clearly hasn't deterred some fish from crossing in the 14 years since. And, according to a recent report, it needs billions of dollars in upgrades and augmentation by other systems — and even then it might not work.

But Asian carp wasn’t the first failure for the barrier system of electrical grids, which were laid across the bottom of a canal to deliver a jolt of current that theoretically would deter fish from swimming across.

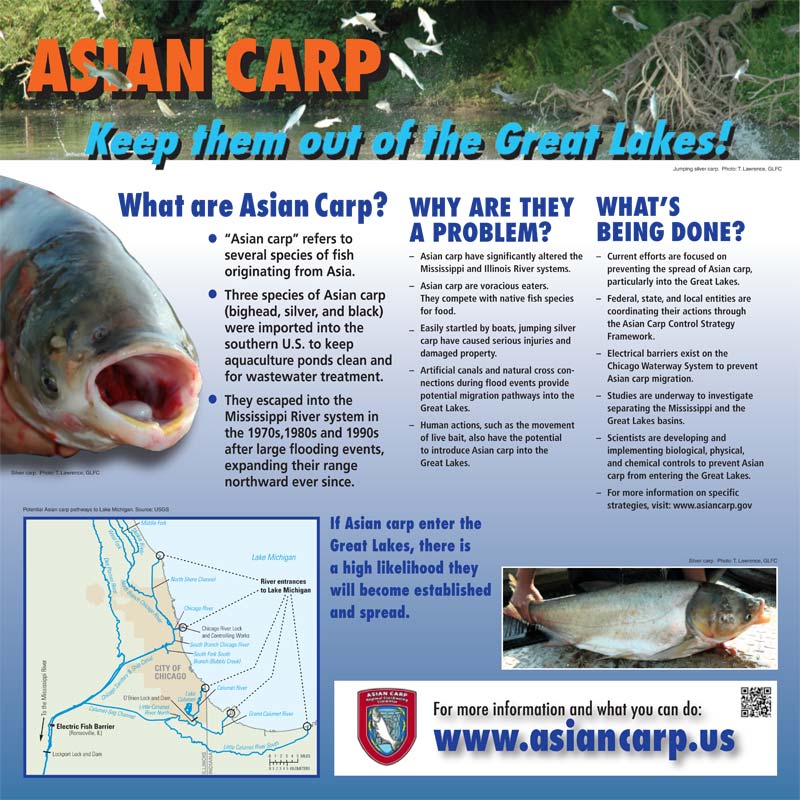

The initial purpose of the barrier was aimed at stopping critters coming from the other direction, European round gobies, an invasive species first spotted in the Great Lakes in 1990, which authorities were trying to stop from swimming down the Chicago waterway to the Mississippi-Missouri River system.

That didn’t work, either. And numerous environmental groups are concerned that the Corps of Engineers, which has avoided making recommendations on how to proceed, will use the complexities of its latest report to delay work that could be done very quickly and at least slow the rate at which Asian carp and other invasive species are getting into the Great Lakes from the Mississippi system, and vice versa.

Apparently the gobies didn’t mind the electrical field, or someone forgot that a goby stunned by the charge would still drift downstream with the canal’s current. Or maybe the gobies got across during the weeks when the Corps of Engineers shut down the electrical barrier for maintenance and there was nothing to stop fish from passing through.

Whatever the reason, the round goby has since reached the Illinois River, from where it has the potential to colonize streams throughout the massive Mississippi-Missouri basin that sprawls across most of the American heartland.

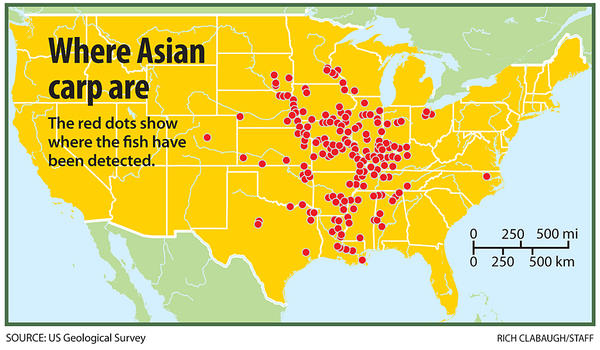

Asian carp, meanwhile, which were first imported to the South in the 1970s, came up the Mississippi to the Illinois River and are now just 50 miles downstream from Lake Michigan, with some evidence that at least a few have crossed into the big lake.

Michigan Sen. Carl Levin has been holding the Corps of Engineers to account in hearings aimed at finding the best way to prevent Asian carp and other invasive species from going between the Mississippi and the Great Lakes. Levin is among those who ultimately support complete separation of the Mississippi and its tributaries from the Great Lakes. The Army Corps of Engineers has put the cost of that at $15 billion or more, a figure that has been questioned by Levin and others as inflated.

In April, a spokesperson for Levin’s office said that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had come up with some good news — a study that showed that the small fish seen crossing the electric barrier probably aren’t Asian carp.

The Fish and Wildlife study found that the nearest suitable Asian carp spawning grounds are far downstream, and Asian carp small enough to cross the electrical field were unlikely to travel that far upriver. But the spokesperson said that Fish and Wildlife had yet to provide a written report of those findings, which is needed for other scientists to vet the conclusions.

Also in April, a meeting among governors of eight Great Lakes states and premiers of Ontario and Quebec ended with hopeful words about protecting the lakes from invasive species, but the same stalemate over how best to do it.

Indiana and Illinois oppose closing the Chicago canal because it would cost businesses there money. The canal is also used to run off floodwaters during heavy rains in the Chicago area and to to drain stormwater and sewage systems. Canada, along with Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York want to cut off the Mississippi from Lake Michigan because invasive species threaten multi-billion-dollar fishing and tourism industries.

David Hamilton, a policy advisor on Great Lakes issues for the Nature Conservancy, an environmental group, said the U.S. government should support a multi-pronged attack on the problem, doing what it can immediately while developing a long-term agreement to permanently separate the Great Lakes and Mississippi basins.

“The cost estimate by the Corps of Engineers is very high because the Corps made some very poor assumptions,” he said, including that most of the work would have to be done before the barrier would be effective. And Hamilton pointed out that Asian carp “are now reproducing in places where no one thought they could. But Asian carp isn’t the problem. It’s a symptom of the problem.

“We’re allowing species to be imported and sold in North America without knowing what the effects will be. Complete and immediate separation (of the waterways) isn’t realistic right now, but if we can’t stop everything at once, let’s at least start working on the problem.”

A decade of failure

When I went to Illinois for the first time to write about the nascent Asian carp threat in 2002, I spent an afternoon with scientists who had been contracted by the U.S Army Corps of Engineers to run tests to determine if electricity could be used to stop the fish. They had built a small-scale version of the barrier in a concrete ditch, and they said that while the adults were turned back by the charge they were using, juvenile carp seemed unfazed by it and routinely swam across.

The Corps had already installed a demonstration barrier in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, which links Lake Michigan to tributaries leading to the Mississippi. But local environmental activists complained that it often wasn’t hooked up to a power source. They also pointed out that the swirling currents set up by passing barges were likely to pull even larger fish across the electrical field, something the Corps now also acknowledges is a possibility.

The Corps built two larger barriers over the next decade with much more robust electrical conductors, but they had to be shut down occasionally for maintenance. And there was another problem. It turned out that if the electrical charge in the water was enough to deter the carp, it threatened the lives of people who fell into the water and also could create sparks on metal ships and barges, some of which carried potentially explosive materials.

The Corps experimented with various levels of electrical charge while insisting that the barrier was working. Meanwhile, a new technique called eDNA (environmental DNA), developed by Dr. David Lodge at the University of Notre Dame, was able to test water samples for DNA evidence of living animals. Several of those tests found Asian carp DNA in Calumet Harbor near Chicago, which is open to Lake Michigan. Asian carp DNA also has been detected at several other places around lakes Michigan and Erie, although only one adult Asian carp has been caught above the electrical barriers.

Then last January, the Corps released the results of a $25 million study that Levin had pushed for. It confirmed what critics had been saying for nearly 15 years — passing barges could weaken or eliminate the electrical field and allow adult fish to cross the electrical barriers. Underwater video cameras placed in the canal by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service showed schools of small fish routinely swimming across the barriers.

The report said that closing off the Chicago canal would cost more than $18 billion and take 25 years to complete. Advocacy groups like the Great Lakes Fishery Commision and National Wildlife Federation that read the Corps report concluded that only about $2 billion would be required to close off the canal. But Levin’s office said when he raised that point the Corps responded that the physical barrier could not be done without spending roughly $16 billion to address flood control, sewage diversions and other problems that the barrier would create for the city of Chicago.

Chuck Shea, who manages the barrier project for the Army, told Bridge, “We are doing laboratory studies of some of the weaknesses that have been identified. We’re also preparing to build a permanent barrier” to replace the existing barriers, which are considered demonstration models.

Shea said that the new barrier would be more powerful than the existing demonstration barrier, which would also be updated. And new testing would be done with current strength and pulsing to see if that would make the system more effective against carp and less dangerous to people and ship traffic.

The Corps’ report was rebutted by a report by the Great Lakes Commission and supported by a couple dozen environmental groups concerned with the problems of invasive species in the Great Lakes.

That consensus report said the costs cited by the Corps of Engineers included sewage and flood control projects that the City of Chicago would have to undertake anyway and which shouldn’t be included as costs of closing off the waterway. The true cost of blocking the Mississippi waters from Lake Michigan would be $2-$5 billion depending on which method was selected, and could be completed within 10 years, the Commission report concluded.

Marc Smith of the National Wildlife Federation, one of the supporting groups, said the Corps of Engineers laid out the problems and several possible means of solving them but failed to offer guidance on what should be done.

“We need to work toward a long-term solution, but there are things we can do now. We can’t wait for a consensus on what separation (of the watersheds) should look like,” he said. “The Corps of Engineers put together a report with shaky-at-best direction, but they aren’t moving from there. Now they’ve decided to wait for Congress to tell them what to do.”

Smith said that even before a decision is reached on how or if to close the Chicago canal, other methods could be tried, including new locks and dams far downstream, water cannons that blast fish out of an area, bubbler devices that might keep fish from crossing and even fish-specific poisons in some stretches.

Opponents of closing the Chicago waterway argue that bighead and silver carp are unlikely to pose much of a problem in the Great Lakes because conditions aren’t right for them to spawn successfully.

Proponents reply that places like Green Bay on Lake Michigan, Saginaw Bay on Lake Huron and all of Lake Erie offer ideal habitat for the invaders to both feed and spawn, raising fears that the invasive carp will devour plankton that Great Lakes commercial and sports fish also depend on. And a study from the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans found that all five of the Great Lakes offered some waters suitable for Asian carp to become established.

That Canadian report also said that if Asian carp manage to get into the lakes, they will disrupt the native species and radically change the ecosystem. Even more alarming, the Canadian scientists concluded that it would take as few as 10 mature female Asian and fewer than 10 males to create a sustainable population.

A Chicago route

The roots of the present Asian carp problem reach into the last quarter of the 19th century, when the population of Chicago exploded from 300,000 to more than 1.5 million. Typhoid and other waterborne diseases were endemic, and local streams that flowed into Lake Michigan were used as sewage and waste dumps.

Chicago was becoming Carl Sandburg’s “Hog butcher to the world.” One branch of the Chicago River was so filled with rotting debris from stockyards and meat packing plants that it was called Bubbly Creek.

It became obvious the city couldn’t keep dumping sewage and other pollutants into the same Lake Michigan waters that its citizens drank every day. Before 1900, the Chicago River flowed into the 22,000-square-mile lake.

Then some bright spark in the civil engineering department came up with an idea:

Let’s reverse that river so that it flows out of Lake Michigan and sends all of our sewage downstream to the Des Plaines River, the Illinois and hopefully all the way to the Mississippi after enough years of spring freshets.

No one seems to have given much thought to what that might do to the health and welfare of people living downstream. But the U.S. population in 1900 was 76 million, about a quarter of what it is today, and most of Illinois consisted of small towns surrounded by sparsely-populated farmland (still true today).

So a series of locks and canals were built on the main stream and several smaller creeks and the Chicago River was reversed to flow out of Lake Michigan rather than in. It was an environmental boondoggle that could not even be considered today, but it was a triumph of technology that 100 years later was hailed as “The Engineering Monument of the Millennium” by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Today, Chicago still needs the canal to send treated sewage water to the Illinois and Mississippi rivers, and it would take billions of dollars to build new sewage systems to replace it. And some businesses rely on the canal to move goods mostly in and out of Chicago, although there is relatively little commercial through traffic to the Great Lakes.

Murray Johnson, a former member of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, said in his recent book, “The Great Lakes Ecosystem: Uses, Abuses and the Need for a Course Correction” that “Regrettably, business interests are gaining greater control over government policy and programs. At the present time in Canada and until recently in the U.S. governments grew more and more antagonistic to their own scientific staffs.

“They became blatantly hostile to pro-environment groups, branding some as illegitimate radicals. The socio-economic paradigm, with business at the center, leads us to environmental, social and economic crises that expose the flaws in our society.

"There may be no better example of Johnson’s criticism than the dispute over closing the Chicago waterway, where government agencies have attacked the findings of the scientists those agencies hired.

"The Chicago area waterways are only one of several places that offer carp a pathway to the Great Lakes, all of which will likely become economic battlegrounds. The Wabash River in Indiana and the Muskingum River in Ohio also have been infested with Asian carp, and there is a danger that normal spring flooding between small creeks and rivers like the Wabash in Indiana and Maumee in Ohio also could offer a routes into the Great Lakes.

"After bighead carp DNA was detected in 12 of 222 water samples from the Muskingum 80 miles above the Ohio, John Navarro of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources told reporters, ”This information seems to indicate they have already gotten past the dams. They’ve shown no tendency to slow down. They are barreling up these waterways."

An apocryphal quote has Winston Churchill saying, “You can always count on Americans to do the right thing — after they’ve tried everything else.”

The quote is apocryphal because no one has been able to find a printed version. Despite its fuzzy provenance, you won’t find a better example of its validity than the way we’ve handled the threat that Asian carp pose to the Great Lakes.

Eric Sharp worked for 48 years as a reporter for the Buffalo Evening News, The Associated Press, The Miami Herald, The Detroit Free Press and numerous magazines, mostly writing about environmental and outdoors issues before officially retiring from the Free Press in 2012. He now splits his year between Florida, Michigan and western New York State where he continues to write about the same issues and is completing a book about environmental changes in the Great Lakes.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Asian carp are known for leaping out of the water at the sound of boat motors, which has resulted in injuries to boaters. (Photo courtesy the Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee)

Asian carp are known for leaping out of the water at the sound of boat motors, which has resulted in injuries to boaters. (Photo courtesy the Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee)

U.S. Sen. Carl Levin of Michigan has expressed frustration with the pace of efforts to block Asian Carp from the Great Lakes. (courtesy photo)

U.S. Sen. Carl Levin of Michigan has expressed frustration with the pace of efforts to block Asian Carp from the Great Lakes. (courtesy photo) The government and environmental groups are putting out warnings about Asian carp across the Midwest and along the Mississippi River. (Source: Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee)

The government and environmental groups are putting out warnings about Asian carp across the Midwest and along the Mississippi River. (Source: Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee)