Giving Michigan nurses more authority to prescribe drugs and treat patients

More times than she can count, MaryLee Pakieser said she has wished that the rules that govern medical care in Michigan would allow her to do her job.

A registered nurse for 43 years and nurse practitioner in the northern Lower Peninsula for 20, Pakieser said unnecessary delays crop up when one of her rural patients has to fill a prescription. Even though she prescribed the medication and said she likely knows the patient best, the name printed on the prescription bottle is usually that of the doctor with whom she collaborates. Under Michigan law, Pakieser is allowed to write prescriptions only under collaborative agreement with a physician.

“The pharmacy won't call me, they will call the physician,” she said. “Instead of five or 10 minutes to resolve, you added an hour or two while the physician is trying to figure out what is going on. They don't know all my patients.”

Not long ago, one of her patients walked into the emergency room at Munson Medical Center in Traverse City with a cough and infection. Pakieser is his primary care provider through a clinic that treats Medicaid patients who also have mental health issues. But hospital officials asked him for his primary care physician – and he told them he didn't have one.

A few days later, not responding to his medication, he was back in the ER. Pakieser said she could have prevented that second ER trip had she been alerted to his condition. “That information never got back to me,” Pakieser said.

Such confusion and delays could be reduced if Michigan joins a growing list of states that allow advanced practice registered nurses – who are more highly trained than registered nurses – more authority to diagnose, treat and prescribe medications for patients independent of a physician, supporters of this movement argue.

More coverage: Husband and wife, doctor and nurse, at odds over nurses' roles

It is a measure advocates and some legislators say could drive down costs and improve health care, especially in rural regions of Michigan as well as underserved urban areas. Earlier this year, Nebraska and Maryland approved that authority for nurse practitioners, bringing the total to 21 states.

But the idea continues to meet resistance in Michigan, particularly from the Michigan State Medical Society, which represents 15,000 physicians in Michigan.

“Nurse practitioners are wonderful,” said Rose Ramirez, a physician, former nurse and current president of the medical society, “but I think they need some kind of supervision and oversight. The best health care teams are physician led. I worry about the safety of the patients in our state who deserve to have well trained physicians supervising their care.”

Ramirez noted that physicians have a minimum of 11 years of education and training, including four years of college, four years of medical school and at least three years of residency training.

In Michigan, an advanced practice registered nurse must complete a nationally accredited master's degree program in nursing, pass the national board tests for their practice specialty and hold a registered nurse license from the state. Their master's degree includes a minimum of 500 hours of clinical training and their education, including undergraduate and graduate school, typically totals six years.

“Advanced practice registered nurse” is a broad category that includes nurse practitioners, certified nurse midwives, certified nurse anesthetists and clinical nurse specialists. Nurse practitioners engage in practice specialties that include adult and older patients, family practice and pediatric patients.

“Physicians have a great deal more education than nurse practitioners do and they have a lot more hands-on clinical training than advanced practice registered nurses,” Ramirez added.

Nurses as the face of medical care

Nurses are indisputably central to health care in Michigan. According to a 2013 survey by the Michigan Center for Nursing, there were about 133,000 licensed nurses in active practice in Michigan, of which 103,000 were registered nurses. Of those, approximately 4,700 were nurse practitioners, who serve as primary care providers for thousands of patients. In 2014, there were about 34,000 licensed physicians in active practice, of which about 16,000 are primary care physicians.

Proponents of giving highly trained nurses greater authority to diagnose and treat patients say the evidence shows that safety concerns are unfounded, despite the gap in training between physicians and nurses.

“People that are arguing that nurse practitioners are not safe are not arguing with the data,” said Kim Sibilsky, CEO of the Michigan Primary Care Association, a federally-funded nonprofit that oversees 40 health care operations in 250 medically underserved areas of Michigan

“I am not an advocate for physicians or for nurse practitioners. I am an advocate for comprehensive quality of care for people in underserved areas.”

Sibilsky contends it's a common misconception that nurse practitioners, if granted authority to practice independently, would suddenly make medical decisions for which they aren’t qualified. She said nurses are bound – as are doctors – by professional ethics that guide those decisions. In her experience, nurse practitioners readily refer patients to physicians when they encounter medical conditions outside their base of knowledge.

Typically, a family practice nurse practitioner will treat common conditions including minor injuries, routine infections and manage chronic conditions like high blood pressure, asthma and diabetes. A nurse practitioner is trained to refer more complicated conditions and more serious injuries to a physician.

“It's my belief that the vast majority of nurse practitioners know how to work well with physicians and are not inclined to work outside their scope,” Sibilsky said. “That's how they were trained. That's what they do.”

Satisfaction with nursing care

She and others cite studies that appear to confirm the pluses of expanding scope of practice for nurses with advanced training:

A review of medical literature covering 18 years, from 1990 to 2008, found no difference in either length of stay or mortality for a variety of patients cared for by physicians and by nurse practitioners. Patients treated by nurse practitioners also had similar rates of patient satisfaction, emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

In a 2012 review of medical literature, the National Governors Association concluded that “most studies showed that NP-provided care is comparable to physician-provided care on several process and outcome measures. Moreover, the studies suggest that NPs may provide improved access to care.”

A review in Health Affairs of studies involving insurance claim data found “demonstrated lower costs associated with (nurse practitioners’) care.” The report also noted that state restrictions on nurse practitioners seemed to be driven by “professional jockeying” by the medical establishment rather than treatment concerns. “Fearing increased competition, professional medical groups, health care systems, and managed care organizations have typically resisted expanding the practice scope of nurse practitioners,” the authors wrote. “Without an opposing outcry from consumers, patients, family members, and other stakeholders, insufficient stimulus exists among policy makers to respond to organized medicine.”

A study of health care costs in Massachusetts by the Rand Corporation, a nonprofit research organiation, concluded that expanding the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and physician assistants could cut medical spending in that state by $4 billion to $8 billion over the course of 10 years. Massachusetts spends about $60 billion a year on health care.

Sibilsky said that rural areas – where it is often hard to attract and retain physicians – would most benefit from giving more autonomy to nurse practitioners. Recent studies, including a June report from the Lansing-based Citizens Research Council, point to an ongoing shortage of physicians in rural Michigan, particularly northern Michigan, that is projected to worsen in coming years.

From 1979 to 1985, Sibilsky said, she oversaw health care clinics within the Alcona Health Center in rural northern Michigan. She said nurse practitioners and physician assistants were pivotal to their success, in part because nurse practitioners were more inclined to remain in practice in remote areas than physicians.

“The nurse practitioners and physician assistants, they were the foundation for health care in those areas. Those were the folks we recruited and they stayed.”

Physicians oppose expanded practice

In 2013, legislation to grant advanced practice registered nurses full practice authority passed the Michigan Senate 20-18, but died in the House last year amid opposition from the Michigan State Medical Society and other medical groups.

State Rep. Ken Yonker, R-Allegan County, a member of the Health Policy Committee, said he intends to introduce legislation this fall that would go part way to granting that authority. Yonker said the measure would rewrite the state health public health code to define the role of advanced practice registered nurses. It would also grant those nurses authority to prescribe medication without physician approval, with the exception of certain narcotics. But their ability to diagnose and treat patients independently would still be limited.

Yonker sees it as a possible first step toward granting full practice authority.

“Everybody wants to protect their industry and their value,” he said. “The lobbying against it is very powerful. It's hard to get the votes, especially when you have two doctors on the committee.”

The House Health Policy Committee includes state Rep. John Bizon, R-Battle Creek, a physician who remains skeptical about expanding scope of practice for advanced practice registered nurses. Committee chair Mike Callton, R-Barry County, is a chiropractor.

“I would be a little concerned about it, because their knowledge base and training base are a little different,” Bizon said of the nurses. “If you are going to have a captain of a team, I would prefer that that captain be a physician because I think their training is a little more extensive.

They could probably handle about 60 percent or 70 percent of what I do. For many of our patients, the nurse practitioner is their primary care provider. – Tom Marshall, chief medical officer, Alcona Health Center

“If you say they are the same as physicians, they aren't.”

Tom Marshall, a physician, is chief medical officer for the Alcona Health Center, where he said restrictions on nurse practitioners for prescribing some medications is at times a bureaucratic headache. The federally-funded center encompasses nine clinics that serve rural patients in Alcona, Alpena, Iosco, and Emmet counties, many living below the poverty level.

The clinics depend on a combination of physicians, physician assistants and nurse practitioners to deliver care. But while physician assistants can write prescriptions for narcotic pain medications on their own, nurse practitioners have to seek the signature of a physician. (Training for physician assistants is based on the physician model - PAs typically complete a two-year master’s program beyond a four-year undergraduate program, as well as clinical training at some schools of up to 2,000 hours.)

“It's a pain in the butt for us, frankly,” Marshall said.

Marshall said the eight nurse practitioners scattered among the clinic sites are a vital piece of the health care they provide.

“They do a great job,” he said. “They could probably handle about 60 percent or 70 percent of what I do. For many of our patients, the nurse practitioner is their primary care provider.”

Marshall said he did have some concern about what might happen should nurse practitioners receive expanded practice authority and decide to set up an independent practice with no connection to a physician.

“To know what you don't know is probably the most important thing,” Marshall said. “If they can hold true to what they've been trained to do and when they get out of their comfort zone, to refer the patient to somebody that can handle it, great.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

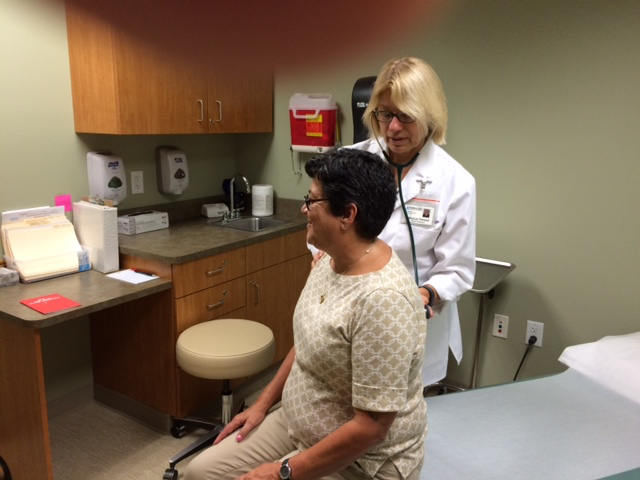

Nurse practitioner MaryLee Pakieser said she believes expanded practice rights would cut needless red tape. (Courtesy photo)

Nurse practitioner MaryLee Pakieser said she believes expanded practice rights would cut needless red tape. (Courtesy photo) Michigan State Medical Society president Rose Ramirez: “The best health care teams are physician led.” (Courtesy photo)

Michigan State Medical Society president Rose Ramirez: “The best health care teams are physician led.” (Courtesy photo)