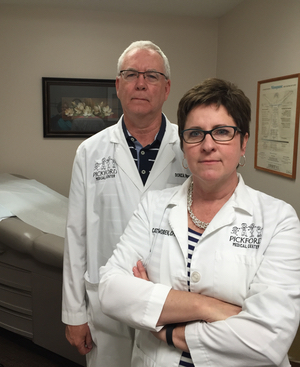

Husband and wife, doctor and nurse, at odds over nurses’ roles

At their home on Drummond Island off the east edge of the Upper Peninsula, dinner-time conversation can take on a distinctly medical flavor.

Donza Worden, a physician, has reservations about allowing nurses with advanced training to make medical diagnoses and prescribe medications without having to collaborate with a physician. Across the table, his wife, Catherine, a nurse practitioner – a specialty that requires a master's degree in nursing - has years of experience that lends her a different perspective.

“Many other states have independent practice (for nurse practitioners) now,” Catherine Worden said. “None of that data can show that there have been any harmful results to patients.”

Her husband issues a more cautionary take on a proposal – standard in 21 other states – that would allow Michigan nurses with a RN license and master's degree in nursing to practice and prescribe drugs for patients independent of a physician.

“In my experience hiring and working with 30 to 40 nurse practitioners over the years, I have not encountered a single nurse practitioner coming out of school who is prepared to practice autonomously,” said Donza Worden, 61. “The most efficient practice model is to have one physician collaborating with two nurse practitioners in rural health.”

Under current Michigan law, nurses must have a collaborative agreement with a physician to prescribe medications and there are some drugs they cannot prescribe, even with that agreement. Catherine Worden has that collaborative agreement with her husband, along with another nurse practitioner in the clinic they share on the east side of the UP, Pickford Medical Center.

More coverage: Giving Michigan nurses more authority to prescribe drugs and treat patients

Catherine Worden, 54, said she draws upon extensive clinical experience and education in deciding which patients she can competently treat and which she needs to refer to a physician.

After earning a bachelor's degree in 1983, Catherine Worden worked as a registered nurse in multiple specialties, including oncology, and as nursing supervisor in three hospitals. She returned to school in 1994 while she raised their two children, earning a master's degree in nursing from Michigan State University in 2000.

“All through school, you hear the words, scope of practice, scope of practice,” she said. “At MSU, I remember hearing that you can do about 80 percent of what a physician can do. You need to be able to recognize that other 20 percent.”

That 80 percent would encompass tasks like routine physical examinations, ordering of X-rays and other tests, treatment of common injuries and infections and managing chronic conditions such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension. The 20 percent might include more complicated conditions including major injuries, serious infections or various heart conditions.

Catherine Worden said her knowledge of her own professional boundaries is reinforced by the training and career track of their daughter, Erin, who is her fourth year of medical school at the University of Cincinnati.

“I know first hand that I don't have the same training as she does. What you need to be able to recognize is when you don't know something.”

In her years as a nurse practitioner, Catherine Worden has been primary care provider for a couple thousand patients scattered across a wide area. She has patients who drive down from Saulte Ste. Marie to see her at the medical clinic in Pickford. Another drives 70 miles from the town of Paradise for appointments. A young woman from Chicago sees her two or three times a year when she returns to visit her parents.

She has occasional frustrations about what she can and cannot do.

She can't sign the death certificate for a patient of hers, even though she may have known and treated the patient for years. She can't prescribe physical therapy. She can't prescribe medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“I'm the one who's working with the family and the patient and yet I can't write those. It's very cumbersome for the patient.”

Catherine Worden said she doesn't believe medical practice would change much if Michigan approved full practice authority for nurses with advanced training – it would simply let them serve these patients more efficiently.

“Nurse practitioners generally see their patients for a long time, just like physicians. But a nurse practitioner is not a doctor, that's the bottom line.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Donza and Catherine Worden share a medical practice, but have decidedly different views about expanding what medical tasks nurses are capable of performing. (Courtesy photo)

Donza and Catherine Worden share a medical practice, but have decidedly different views about expanding what medical tasks nurses are capable of performing. (Courtesy photo)