From Italy to the UP: A mining family album

MARQUETTE COUNTY – In the grainy black-and-white photo, taken c. 1920, Pietro Frustaglio sits with his miner's hat in his lap, erect and proud, surrounded by miners that are taller than him.

Documents say he stood 5-foot-3 and weighed 147 pounds, dimensions that might not suggest a lifetime of hard physical labor.

But the Italian native was the original Frustaglio, the first of four generations to carve a living from the Upper Peninsula iron mines. Relatives say he put in 50 years underground before retiring.

It is a family history replicated dozens of times in this part of the UP, where generations of Italians, Finns, Swedes and other immigrants built a life from the earth.

His grandson, Peter Frustaglio Sr., has childhood memories of visiting Pietro's home at Christmas, recalling his grandmother's traditional Italian food. He said his grandfather was always well dressed for the occasion – typically in a dark blue suit, white shirt, contrasting tie, polished shoes. His grandfather died in 1963, when Peter was about 12.

“I always heard he was tough. I think he had to be,” said Frustaglio, 74, who logged 30 years in mining himself before retiring in 2004. His son, Peter Jr., followed him into the mines in 1998.

Barry James, a historian for the Michigan Iron Industry Museum in Negaunee, said the mines opened opportunity for generations of immigrants and defined the local communities.

More coverage: Mining's last stand? A UP way of life is threatened

“At the turn of the last century, Negaunee was about 7,000 people. There were 10 mines within the city limits,” James said. Negaunee has about 4,600 people today. Ishpeming had more than 13,000 people in 1900. It has about 6,500 today.

“A lot of times, the father would come (from overseas) first to get a job in the mines and then they would send for their family.”

Even in these relatively small communities, James said, ethnic groups stuck to their own kind.

“The Italians would hang out with the Italians, the Finns with the Finns, the Swedes with the Swedes.”

According to what appears to be an application for citizenship in a Frustaglio family album, Pietro emigrated from Italy, through Boston, to the United States in 1903 at the age of 16. The album states that he believed the streets of America were “paved with gold.”

The document states that he settled in Ishpeming with a sister, at which time he may well have started in the mines. He married his wife, Rose, in 1908 and they would go on to have 10 children, living for decades in the same two-story wood frame house in Ishpeming. They were devout Catholics, faithful worshipers at nearby St. John the Evangelist Church.

The youngest of his five sons, Ishpeming resident Vito Frustaglio, 80, said that his father never complained about his job. He said he was grateful to escape the poverty his family endured in Italy for a new chance at life.

“They came from nothing,” he said. “They were starving in Italy. I think it was paradise for him, to come to a country where they could make a living.”

Vito said three of his older brothers followed their father into mining – Dominic and Phillip, both of whom made it their career – and Peter, who worked briefly in the mines before becoming a barber.

Vito said he believes his father worked perhaps 50 years, before retiring at about age 65. For much of the time, he loaded ore cars at the mine bottom. It was damp, grimy, dangerous work.

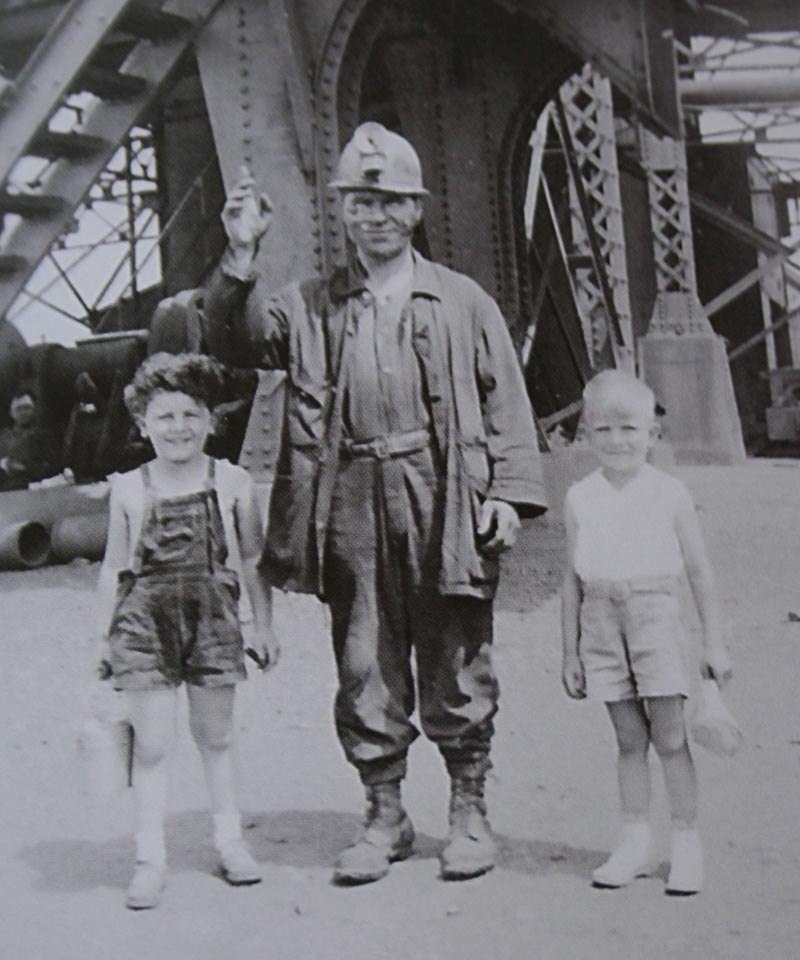

He recalls bringing lunch as a child to his father. There's a picture of one such occasion, taken about 1940, as Vito and another child stand next to Pietro. His father stands with his right arm raised in the air, index finger pointed to the sky as if offering a salute.

“I remember he was in his mining clothes. They were dirty, very dirty. But it gave him and his family a living. We were never rich, but they provided for us very well. We always had food on the table.”

Despite that, Vito recalled that his father took him aside one day when he was a teen and quietly told him: “'If you can stay out of the mine, please do it.'”

Vito Frustaglio made his living in sales.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Pietro Frustaglio, pictured around 1920 at center with his hat off, came to the Upper Peninsula in 1903 at 16 for work in the mines. He would raise 10 children and mine for 50 years. (Courtesy photo)

Pietro Frustaglio, pictured around 1920 at center with his hat off, came to the Upper Peninsula in 1903 at 16 for work in the mines. He would raise 10 children and mine for 50 years. (Courtesy photo) Pietro Frustaglio stands with his youngest son, Vito, at right, and another child. (Courtesy photo)

Pietro Frustaglio stands with his youngest son, Vito, at right, and another child. (Courtesy photo)