Kalamazoo gains strength from Promise

Jasmine Granville learned about the Kalamazoo Promise riding the bus back from a basketball game at Battle Creek Central. "I don't remember if they played it on the radio, or people were calling people," she said. "I remember a bunch of the seniors were just bawling their eyes out."

As a freshman at Kalamazoo Central High School, she didn't see what the big deal was. She was hoping for a full-ride basketball scholarship, and if that didn't work out, well, neither would college. Where she grew up, it was sports or the streets. But when she discovered as a senior that the basketball scholarship wouldn't pan out, she realized the importance of the Promise.

"The Promise completely changed my outlook on the future," said Granville, who is attending Kalamazoo Valley Community College and plans to transfer to Western Michigan University next fall. "Without it, I would not be in school."

A surge in college enrollment for eligible students is just one of the promising trends credited to the Promise.

The Kalamazoo Promise, launched by anonymous donors beginning with graduates of the class of 2006, pays for free tuition at Michigan's 15 public universities and 28 community colleges to all Kalamazoo Public School graduates who attended KPS schools from kindergarten through 12th grade. (Scholarships are prorated for other graduates who have attended KPS schools for at least their final four years. Graduates who attended from grades 9-12 have 65 percent of tuition costs covered, while those attending from first grade on get 95 percent.) About $30 million has been paid out so far by the program.

The Promise, which drew immediate worldwide attention and was highlighted by President Obama in an address to Kalamazoo Central High School's class of 2010, has opened up unprecedented opportunities for Granville and other young people in the Kalamazoo Public Schools by removing the cost of higher education as a barrier to learning. It has fueled a surge in enrollment in KPS and shined a spotlight on the community that economic developers covet and exploit, and aligned educators.

It also is creating unique challenges for those seeking an educational transformation of the region they hope will bring new families to the city and strengthen the economy. Chief among them: raising high school graduation rates and helping more KPS graduates succeed once they reach college.

"I think everyone is pleased with the direction everything is going," said Bob Jorth, executive administrator of the Kalamazoo Promise. "We understand there is a lot of work yet to do."

Promise = more students

The Kalamazoo Promise applies only to graduates of Kalamazoo's public school system who live in the school district. For more than 30 years, the Kalamazoo Public Schools, like many of its urban counterparts, endured a slow but steady reduction in enrollment as middle-class families moved to the suburbs and many that stayed in the city opted for charter, private and parochial schools.

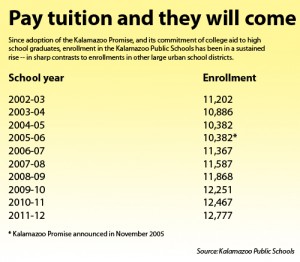

That has changed since the Promise appeared. Enrollment grew by almost 1,000 the first year and has climbed every year since. This falls enrollment of 12,77 is up 23 percent from the pre-Promise figure of 10,382 in the fall of 2005. (See chart at right.) This year's count of 12,777 is the highest since 1987.

And because state funding is tied to enrollment, the additional 2,395 students bring millions of additional dollars annually into the district.

And because state funding is tied to enrollment, the additional 2,395 students bring millions of additional dollars annually into the district.

Initially, most of the growth came from new students enrolling in Kalamazoo schools. Now, however, it comes because fewer students are leaving, according to researchers studying the Promise. "They used to exit at various points along the way," said Michelle Miller-Adams, a visiting scholar at the W.E. Upjohn Institute in Kalamazoo. "The Promise has really created this long-term attachment of families to the school district in the urban core of this region -- and that is very important."

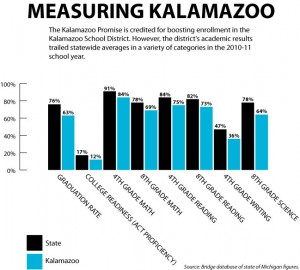

Promise Zone officials are hoping to see an increase in the high school graduation rate, which hovers at about two-thirds, about the same as before the Promise (and below the statewide average). "I think most of us thought we would have seen a big increase in graduation rates, but for some reason that hasn't happened," Jorth said.

More start college

Not surprisingly, more Kalamazoo Public School graduates are going to college now that the donors are paying the bills. Nearly 90 percent of the graduates who attended the schools long enough to be eligible for the Kalamazoo Promise are enrolling in higher education institutions, a strong number for a suburban school system and remarkable for an urban district.

About two-thirds are attending public universities -- with about 90 percent of those at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan State University or the University of Michigan. The other one-third attend community colleges, most commonly KVCC.

Of course, the ultimate goal is not college attendance, but college degrees and a well-educated, well-credentialed work force that meets the needs of current employers and attracts new businesses looking to set up shop in the smart city. In that regard, the results from the first years of the Kalamazoo Promise are both a source of pride and a stark reminder of the challenges ahead.

For Kalamazoo Promise students attending public universities, which admit students based on their academic qualifications, the chances of success are high. About 85 percent return for the second year, a number that is as good or better than in most schools. So far, about 130 have earned bachelor's degrees.

But for those attending community colleges, which accept all high school graduates regardless of their grade point, the prospects for success are substantially less. Fewer than half come back the second year, Miller-Adams said, which is similar to other schools. Students have up to 10 years to use their Promise Scholarships, so there are opportunities to come back and complete degrees. There's reason to hope the stats will improve as students grow up knowing college is in their future.

"The community college is responding with a lot of resources to support incoming students, and the school district is working really hard, too," said Miller-Adams. "The students were already in high school when the promise That was announced and didn't have a lot of time to prepare for college-going curriculum," she said. "I don't think you'll really see the impact until you see the kids who've gone through 12 or 13 years of the system where they have been told every year they will go to college, we have faith in you."

Kalamazoo Valley Community College has taken a number of steps to provide better support through its Student Success Center. "Primarily we try to get them hooked up with what we call 'success advocates,' who really help them navigate the higher education experience," said Mike Collins, vice president for college and student relations. "If they need help with a class, we get them hooked up with our tutoring center. If they're having life issues, we try to help them with some of those."

Focus turns to improving schools

While there are efforts to help students who come to college with deficiencies, there's also a determined effort to ensure that graduates in the future are better prepared. It is a strategy that begins long before children walk into classrooms for the first time.

This summer, an $11 million educational support was launched to help children from infancy through college. The countywide Learning Network of Greater Kalamazoo is focusing on literacy and community engagement. Early efforts include courses for parents of newborns and preschoolers and programs to promote family literacy.

This summer, an $11 million educational support was launched to help children from infancy through college. The countywide Learning Network of Greater Kalamazoo is focusing on literacy and community engagement. Early efforts include courses for parents of newborns and preschoolers and programs to promote family literacy.

The public schools have undergone a dramatic transformation of their own since the beginning of the Kalamazoo Promise.

The district has constructed two new schools, the first since 1972. It has created El Sol, a dual-language elementary school with both English and Spanish, and established a Middle school alternative learning program, a smaller school better equipped to help students with behavior challenges.

It has gone to full-day kindergarten classes using federal Title I funds to assist disadvantaged students. In addition, the district has created a new writing curriculum in early elementary school and replaced its K-5 math series for the first time since 1992. "Basically, we have taken a lot of elements apart and put them back together better than they were," said Superintendent Michael Rice. The payoff: math and reading scores in elementary and middle schools have risen for the past four years.

In high school, students are encouraged to take more rigorous classes. The school offers 16 college-level Advanced Placement classes ranging from calculus to art to European history, and requires students to take the AP exams. The number of students taking them has nearly tripled over the past three years, with even higher growth rates among African-American and low-income students.

"The district used to make Advanced Placement courses the province of particular kids. We have broadened that profoundly," Rice said. "We believe that if you are preparing for college, you need to take college courses."

Changing a culture

One of the keys to success will be rising aspirations. One goal of the Promise is to create a culture where every child expects to go to college. Cailey Cunliffe, a Kalamazoo Scholar from the class of 2010, was in eighth grade when she learned about the Promise. She said it inspired her to work harder.

"I knew that no matter what, I would go to college, but it pushed me harder because I knew I could go to a different university than Western," she said. It expanded her opportunities and has so far allowed her to avoid student loans. She was accepted to Michigan State and started there, before transferring to Western.

The efforts to create the college-going culture begin early. Walk into Parkwood Upjohn Elementary, and you might notice the dates hanging over every classroom. They are just one of many signs telling children and families what lies ahead. "We explain to children that it's not the year they graduate from high school -- is the year they begin college," said school Principal Carol Steiner. "It serves as a visual reminder that it is in their future.

And then there's College Week, where every teacher selects a college and shares information about it.

"I think we are doing a better job of communicating to the students and to the parents that they have this possibility that they perhaps never had before. And the parents are starting to believe it," Steiner said. "Even last year, there were still parents who are saying the money won't be there for my child."

It takes 18 years, though, to grow a high school graduate, Superintendent Rice says. "We are on the right path. The experience that children are getting is a stronger experience than they got before," he said.

The Kalamazoo Public Schools' greatest challenge is whether the state will maintain adequate and stable funding, something he says it has failed to do in the past several years. "In the absence of that, there will be no shelter from that unhappy financial storm. None," Rice said. "It doesn't matter whether you are talking about the Promise district or any other district for that matter, school districts and the education within them will deteriorate if the state does not stably and adequately fund public schools."

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!