With bedtime stories and growing unease, a Michigan elementary confronts coronavirus

The bedtime story was supposed to be a one-night event.

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer had ordered all K-12 schools in the state to close for three weeks to try to staunch the spread of coronavirus, and Principal Michael Prelesnik wanted to offer some comfort to the students at North Aurelius Elementary School in Mason.

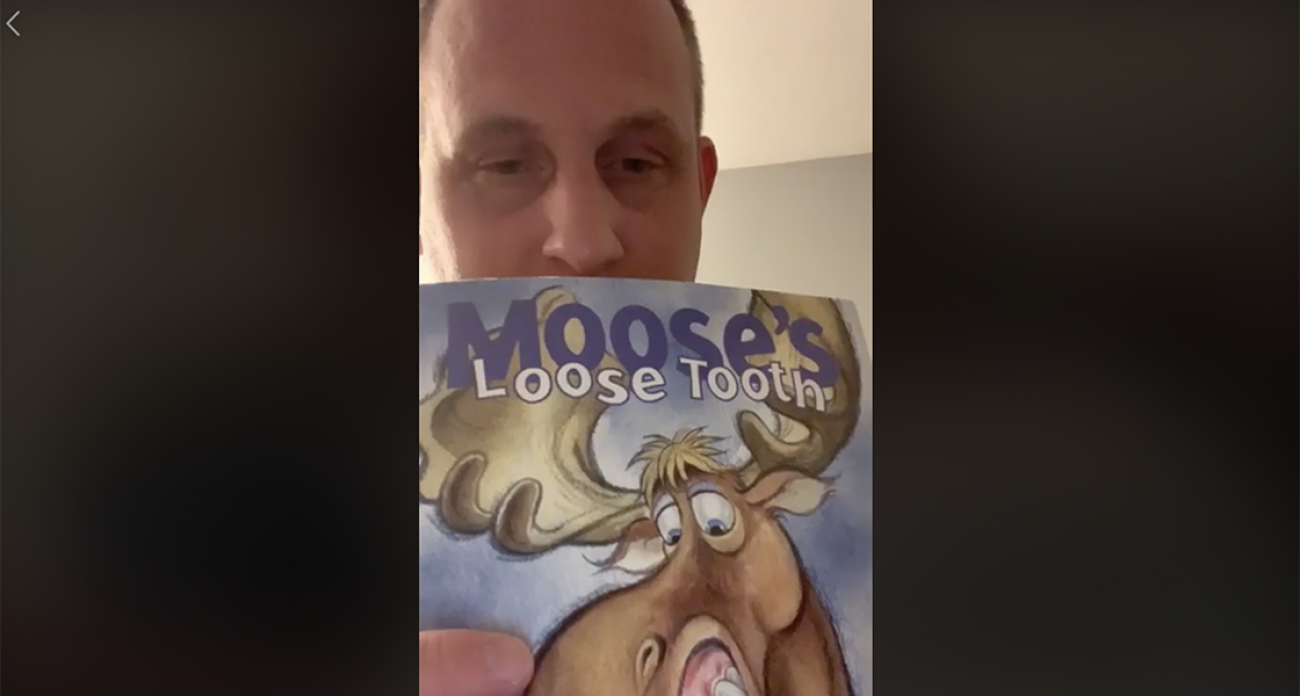

So at 8 p.m. on March 16, the first day of the closure, Prelesnik sat down in a chair in his living room, connected to Facebook Live, and opened a book.

He chose the book partly for its title: “We can do this together.”

The bedtime story was such a hit, Prelesnik decided to do it the next night, too, and the night after. “Curious George” gave way to books from the “Little Critter” series, with teachers and students often e-chatting on the website as the principal read.

- The latest: Michigan coronavirus map, locations, updated COVID-19 news

- What Michigan’s coronavirus school closure means for you

- What jobs are exempt from Michigan coronavirus lockdown? You may be surprised.

As the books piled up, though, so has unease on the elementary school’s staff. “This is the third week [of school closure], and there’s a lot of anxiety about what the future holds,” Prelesnik said Wednesday. “We’re worried about our kids, socially and emotionally. We were having a great year and our momentum of academic achievement has been interrupted. This is going to affect kids for a long time.”

Teachers at the Ingham County school are “hanging in there,” Prelesnik said, “but the reality is setting in. This is really difficult.”

Thursday, it became much, much more difficult.

What was originally a three-week pause in Michigan’s classrooms to stop the spread of the potentially deadly virus may now be set to stretch to more than five months.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer issued an executive order Thursday closing Michigan classrooms for the remainder of the school year, which typically runs to early June.

Educators now face a sobering reality that, barring emergency funding for school during summer break, they may not come face-to-face with students again until after Labor Day.

Whitmer’s executive order states that while classrooms are closed, education will continue. Michigan schools will provide remote learning to students between now and the end of the school year. What that learning will look like will depend on where you live. School districts and charter schools can create their own remote-learning programs, with approval from their intermediate school districts.

In some districts, that is likely to be decidedly high-tech. West Bloomfield School District, for example, has been offering online classes for its students since mid-March.

Other districts, where some students do not have access to laptops or Internet at home, are likely to rely on packets of homework assignments.

Either way, school leaders acknowledge that the amount of learning is likely to be lower than if children were at their school desks.

“[School officials] are all trying to figure out what they can do to continue education that will be meaningful,” said Ron Koehler, assistant superintendent at Kent Intermediate School District. “If you don’t have [Internet] access, what do we do to provide equitable opportunity? It’s difficult. There’s no way you can put together packets that will be as robust as what kids have access to the Internet.”

No matter how well-thought-out a remote learning plan is, elementary school students aren’t likely to do well without home supervision, Koehler said. “If you don’t have significant parental support, there are going to be kids who are going to fall behind,” Koehler said.

Whitmer tried to address those fears Thursday, saying “students and families will not be punished if they are unable to participate in their alternative learning plan.”

Learning loss over the traditional 2 ½-month summer break is something schools deal with annually, said David Campbell, superintendent of Kalamazoo Intermediate School District. It’s not unusual, particularly in early grades, for teachers to spend several weeks going over materials taught the previous spring.

The possibility of many Michigan students being out of classrooms for almost six months is “beyond crazy,” Campbell said. “When you think of the inequity in the system, this is a great way to expand the achievement gap.”

In Midland Public Schools, superintendent Michael Sharrow said he would ideally like to extend the 2020-21 school year from the state-required 180 days to 195, and start the school year three weeks earlier than normal to all students some time to catch up.

The problem: He doesn’t know where he’d find the money.

Sharrow told Bridge that an extra three weeks of school would likely cost the district $3 million to $4 million.

Thursday’s executive order does not appear to address whether additional state funds would be available for schools to try to address learning loss in the fall.

Sharrow said his staff was making plans to ramp up remote learning between now and the end of May.

“We’re going to try to advance [curriculum],” Sharrow said, “though we know we won’t hit the same spot we would if we were in front of the kids.”

The 7,800-student district purchased 60 WiFi hotspots in preparation for the school closure order, and has set up computer repair centers for school-owned Chromebooks that are now in student homes.

“There will be kids who will advance well and others will not,” Sharrow acknowledged. “You talk about summer slide (learning loss between school years). We’re expecting that to happen maybe double-fold.”

Brian Gutman, communications director for Education Trust-Midwest, cautioned that the academic impact of the coronavirus school closures will be felt “for years.”

“I’m guessing the number of low-income children is about to explode,” Gutman said. Student achievement is stubbornly correlated to income.

Gutman also warned that another vulnerable population – English language learners, may be hit hard by remote learning.

If you’re an English learner, chances are you don’t have someone at home to help you with your lessons, even assuming you have access to online learning,” Gutman said.

At North Aurelius Elementary, remote learning during the closure so far has been minimal, consisting of optional online learning activities. “Nothing is required” for students to do, principal Prelesnik said.

That will likely change following Whitmer’s executive order. Mason schools are surveying students to see who has computers and wifi at home, Prelesnik said. North Aurelius has Chromebooks, but, for now, they are stashed away at the school instead of with homebound students.

“We’re looking at some kind of virtual learning,” Prelesnik said. Educators will meet next week (during Mason Public School’s spring break) to plot logistics for a more robust remote learning than what the school did when school leaders expected kids would return to classrooms.

“We’ll do the best we can with the resources we have,” Prelesnik said. “It’s definitely going to look different.

Thursday night, on the eve of learning that his students wouldn’t be returning to their classrooms this school year, Prelesnik sat down on his living room couch, connected to Facebook Live, and read a bedtime story.

He chose the book partly for the title: “My Social Distancing Story.”

RESOURCES:

- Michigan families can get food, cash, internet during coronavirus crisis

- How to give blood in Michigan during the coronavirus crisis

- 10 ways you can help Michigan hospital workers right now

- Michigan coronavirus Q&A: Reader questions answered

- What Michigan’s coronavirus stay-at-home order means for residents

- How to apply for Michigan unemployment benefits amid coronavirus crisis

- How to get tested for coronavirus in Michigan

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!