Braving Upper Peninsula winters, Michigan Tech grads strike gold

The call has been a shout, not a whisper: We need more kids to get science and engineering degrees! America’s place in the world’s economy is in jeopardy!

Amid the clamor there are serious questions about whether a problem exists, with some experts suggesting there are plenty of qualified STEM graduates in the country already and that expanding STEM programs may create an unnecessary glut of STEM graduates.

“I think this drumbeat of ‘more STEM, more STEM’ has led to hyperbole,” said Hal Salzman, a professor of planning and public policy at Rutgers University. “Are we setting kids up for bad expectations? The answer is yes.”

But Salzman adds that when STEM grads are needed, employers would be wise to recruit workers from “a school that...has a history.”

A school, for instance, like Michigan Tech , which has been attracting bright students and producing engineers and geologists for decades. While a recent U.S. Census report shows STEM grads are often find work outside their fields of study, ninety-five percent of Tech grads are either working or in grad school or the military six months after graduating, earning competitive salaries. The four largest majors, according to a 2012-13 survey, averaged $58,500 in starting salary in civil, chemical, electrical and mechanical engineering.

Heading north

In late September, hundreds of recruiters descended upon tiny Houghton, filling every hotel and motel room in this remote area in the northernmost reaches of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Recruiters filled a four-basketball-court recreation floor with tables and displays, so many that the two-day event spilled over to the school’s basketball arena.

“We have had great success with grads from here,” said Brian Cowell, a mechanical engineer from Plexus, an international electronics manufacturing services company based in Wisconsin. Plexus sent about 10 people to talk with students, collect resumes and schedule interviews. It was a big commitment made by more than 340 other companies who saw Tech’s students as golden economic opportunities.

Companies like Plexus can pick and choose where they go for talent and, recently, another Michigan school was scratched from Plexus’ recruiting list because its grads hadn’t performed. But Tech remains on the list of schools the company visits.

“We hit the ones where we’ve had the best success recruiting at,” Cowell said.

Plexus was joined by companies from across the spectrum, from Ford and 3M to Caterpillar, GM, Kimberly-Clark and Kohler. They were looking for interns and new hires, ready to commit to students, many still too young to legally drink.

Although tiny compared to Michigan State and the University of Michigan, Tech has been producing STEM graduates for decades and is focused on engineering and the sciences. You don’t head to Houghton to get an English degree; the No. 1 degree is mechanical engineering – and the next four are also engineering: chemical, civil, electrical and biomedical. Next after that is computer science. Of the 1,193 first-year students in 2013, roughly 90 percent chose STEM fields.

It’s the type of school Salzman is talking about when he says it “has a history.” Michigan Tech, second to UM in STEM grads in the state and roughly tied with MSU, is largely focused on undergraduate education. It has PhD programs and conducts research, but its professors’ main job is creating a skilled undergraduate able to handle what today’s high-tech world demands.

Judging by the career fair, it’s doing a pretty good job.

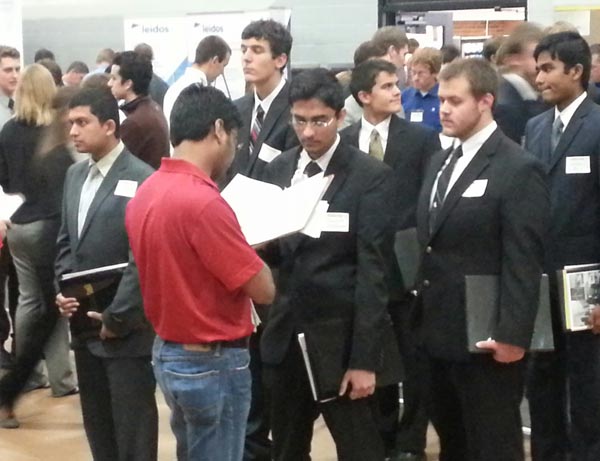

Recruiters fill the athletic halls in matching shirts, some with have T-shirts that read “No Data, No Change.” They hand out tote bags, water bottles, sunglasses and T-shirts while standing in front of displays with sayings like “We don’t fill positions, we engineer opportunities.” When the fair officially opened, a wave of students – even freshmen trying to snag their first internship – pour into the rooms in ill-fitting suits, waiting for the chance to drop off a resume and score an interview.

For those wondering if the economy is thawing, the evidence was in these two rooms, even as the temperature outside was plummeting. More companies came this year than had ever visited before.

“This has by far blown away any other years,” said Steve Patchin, director of career services at Tech. It was the greatest number of companies the campus had ever seen, he said, well more than double the 140 companies that came in 2009.

A tough road

In 2011, Apple chief Steve Jobs told President Obama the nation needed to graduate 10,000 more engineers a year to keep pace internationally, which would mean hundreds more STEM graduates from Michigan colleges, including Michigan Tech.

Yet there are fewer kids graduating from Michigan high schools every year. And although Tech’s undergraduate enrollment is up, it’s only slightly up, in part because it has raised its female student population from 17 percent several years ago to 26 percent this year, President Glenn Mroz said.

Nationally, a greater percentage of high school graduates are going to college, yet only a small fraction are interested in STEM fields. Compounding the problem of finding kids interested in STEM, is finding kids interested and capable enough to handle STEM’s demanding coursework.

“It ain’t easy,” said Mitchell Chang, a professor of higher education and organizational change at UCLA in California. “It’s different from other majors.”

Consider Tech freshmen Ben Bergeron of East Lansing. His courses at Tech include calculus 3, honors composition, programming and non-Euclidean geometry ‒ and that’s in his first semester. Just weeks after settling in on campus, Bergeron was at the career fair, resume in hand. “If they have positions open, I wanted to get my name known to them,” he said.

Bergeron knew what to expect when he got to Houghton, and he was glad that a lot of math and computer work awaited him. But clearly, it’s not for everyone. In Michigan, the group of students considered ready to tackle those challenges isn’t growing: On the state’s Michigan Merit Exam, given annually to high school juniors, only 27 percent were considered proficient in math last spring, and 25 percent were rated proficient in science.

Those figures make it difficult on schools like Michigan Tech to recruit qualified students. One, school officials have to convince this small slice of prospective students to travel to far northern Michigan, where the region averages almost 220 inches (or 18 feet) of snow each winter. One bonus: the university owns a ski hill less than a mile from campus and maintains acres of cross-country skiing trails.

And then, well, students enrolling at Tech must be prepared to work hard. The school has the second highest ACT scores among incoming freshmen of the state’s 15 public universities, second only to UM.

“You don’t want to accept people who don’t have a chance to graduate,” Mroz said.

Why Tech works

On the Monday night before the career fair, the Tech main library was full. Nearly every computer terminal had a student in front of it, most rooms set aside for groups were full of students trying to solve problems.

Tech’s focus on undergraduate students has been in place for years. But the school is still evolving: it’s changing the curriculum to give engineering students an earlier peek at engineering, rather than making them slog through all of the foundational courses before they get the reward of applying their knowledge.And it is emphasizing its “enterprise” program, in which teams of students work on solving companies’ real-world problems, be it in prosthetics or electronics. The students get their hands dirty and the companies get a marketable solution.

The result has been days like the career fair, when the product of the school is up for sale – and there are hundreds of bidders.

“They really like (our) people because they’re ready to go to work,” Mroz said.

Tom Rossmeissl, piping design manager for Jacobs Engineering Group, Inc., a 70,000 employee international company, was more succinct about why his company keeps making the drive from Wisconsin to Houghton: “We’ve never had a dud,” he said.

Of 122 Michigan Tech mechanical engineer grads who got offers in the last year, the average salary was just over $61,000, with the highest offer at $100,000, according to a recent graduate survey. Among other majors where at least 50 graduates got offers, civil engineers were averaging $49,300; chemical engineers $67,400 and electrical engineers $59,100.

Nearly half of Tech grads stay in Michigan, with Wisconsin (16 percent) and Minnesota (9 percent) the next most likely landing places, according to a 2012-13 report.

Not all STEM degrees are gold

Unfortunately, not every school that offers a STEM education is minting degrees as promising as those at Tech, UM and MSU. The push to add students has created new programs across the country, many at schools that don’t have a singular focus or a culture of science and engineering.

“A low-quality STEM program is not going to do you very good,” warned Salzman, the Rutgers professor. “Buyer beware because they’re not all created equal.”

Because of the rigor associated with STEM, dropout rates are high in the first two years. What Chang of UCLA said he has discovered, however, is those schools that specialize in STEM, like MIT, California Tech and Michigan Tech, do a better job at keeping those students who enroll (Tech has an 87 percent retention rate). First, they select kids who want that type of degree and secondly, when adversity arrives, there are fewer non-STEM degrees to fall back on.

That’s not necessarily the case at a school with a broader set of course offerings. “When they switch majors, they don’t switch within science,” Chang said. They may opt for business, or law.

Tech has other programs besides engineering – business, psychology and forestry, for instance – but the school’s bread-and-butter degrees remain tech related, with more than 86 percent of all majors anchored in STEM.

It’s that focus that attracts both STEM students and STEM employers. Senior A.J. Suneson, 21, of Wichita Falls, Texas, traveled a long way to get to Houghton, where he has majored in computer engineering. He handed out seven resumes during the job fair – nearly 90 companies were seeking people with his major – and was hoping to interview with several on the second day of the fair.

In the weeks after the fair, he had a couple of interviews, one solid offer – pay in the $65,000 range – and intends to soon fly to Wisconsin for another interview. Other prospects loom, he said, and he may expand his search. “Market still feels very strong for computer engineers,” he said in a recent email.

The interest from recruiters was a partial reward for more than three years of tough classes and cold weather – he had to knock a foot of snow off his car as he left for Thanksgiving break. But to have one job offer in hand, and the prospect for more?

“It certainly validates the work that you’re doing,” he said.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

More than 340 companies sent representatives to Houghton, making it the largest career day ever, school officials said.

More than 340 companies sent representatives to Houghton, making it the largest career day ever, school officials said. Pensive looking Michigan Tech students await their turn to hand a resume to one of the hundreds of companies looking for talent at the school's annual career fair.

Pensive looking Michigan Tech students await their turn to hand a resume to one of the hundreds of companies looking for talent at the school's annual career fair.