Michigan colleges don’t know if students will return to campus this fall

Already bleeding millions of dollars because of coronavirus campus closures and with no end in sight, college and university officials across Michigan now are wrestling with how — and even if — students can safely return in the fall.

According to Bridge Magazine interviews with officials at state universities and higher education associations, scenarios for fall 2020 being discussed run the gamut from holding the entire semester online, to having students return in September for a normal term, to hybrids that would bring students back for part of the semester or limit the number of students allowed on campus.

Decisions are still at least a month away, officials told Bridge, and will be heavily influenced by the infection trajectory of the potentially deadly coronavirus and executive orders of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. But many acknowledge that college life this fall is likely to look and feel different from semesters in the past.

- The latest: Michigan coronavirus map, locations, updated COVID-19 news

- What Michigan's new coronavirus stay-at-home executive order means

- When Michigan unemployment, stimulus checks, and $600 CARES money will arrive

“There’s still a part of me hoping there will be some resumption of normalcy come this fall,” said Dan Hurley, president of the Michigan Association of State Universities, which represents the state’s 15 public universities. “But the universities are planning around the clock for alternative scenarios.”

The problem, though, for campuses in Michigan and across the country is that they will be forced to make decisions on what to do about the fall semester without having all the answers about the coronavirus that they’d like.

“There are way more unanswered questions than answered questions,” said John Beaghan, vice president for finance and administration at Oakland University. “I’m not a medical guy. If there’s some miraculous treatment that gets announced this afternoon, yeah, it will be a normal semester. But I’m not hearing anyone [talk] like that.”

College officials who spoke to Bridge said they haven’t set a deadline for making decisions on the format of the fall semester. But several experts in higher education economics say decisions will have to be announced by July 1, the beginning of college budget years, to adjust staffing and inform students.

“It’s on everyone’s mind,” said Frim Ampaw, director of the Center for Applied Research in the College of Education and Human Services at Central Michigan University. “They’ll be making decisions my late May to mid-June.”

Michigan State University spokesperson Emily Guerrant said the school is looking at a wide range of options for the fall semester, from “the previous normal, the current situation [online classes], and what’s in-between.

In a virtual town hall Monday, MSU President Samuel Stanley, who is a medical doctor, said the university is making parallel preparations for both a full return to campus, and to continue to provide classes online.

“As the months progress, particularly as we get into June and July, we’ll be in a much better position to really understand what is feasible and what can be done safely,” Stanley said.

“We should be preparing for the possibility of going fully online again,” Stanley acknowledged. “If that is the only way to provide safe instruction, we have to be prepared to do that.”

The situation is similar at the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor.

“Nothing is definite about fall on our campus or just about any college campus,” U-M spokesperson Rick Fitzgerald said in an email. “We have begun to explore what it would take to safely return our employees and our students to campus in the fall. We all hope that with the proper safeguards, whatever they may be, we will be able to deliver classes in person come fall. “But we also will be ready to implement different approaches to teaching and learning, should that be what the situation requires.”

Michigan’s public universities halted in-person classes and moved to online learning March 11, less than 24 hours after the first coronavirus cases were confirmed in the state. By the next day, the state’s private college and universities followed suit.

Most have announced they are moving classes this spring and summer terms online.

Whitmer is expected to begin to ease the state lockdown in May. It’s unclear how quickly limits will be lifted on non-essential work and Whitmer’s stay-at-home order. While data on COVID-19 infections and deaths are trending down, health officials worry a quick return to normalcy could spark a second surge in a state hit brutally by coronavirus infection and death.

The nature of universities — with close-quarter learning, and an age group of students for whom “social distancing” doesn’t come naturally — makes decisions on how to proceed even trickier than it may be for businesses.

Colleges and universities were “built to tightly connect a large community of individuals so each can learn from every other with as little effort as possible,” Timothy A. McKay, associate dean for undergraduate education at U-M, told the Chronicle of Higher Education. “Such a small-world community is great for spreading ideas. It’s also, in some ways, great for spreading a contagious disease.”

A study conducted at Cornell University suggests that the average college student comes in contact with about 500 other students a week just in various classes, not counting dorms, cafeterias and social activities. Because many who contract the coronavirus show no symptoms at all or don’t show symptoms for one to two weeks, the potentially deadly virus could spread quickly on a campus.

“The most realistic scenarios are not about whether we have a completely normal semester, but about how far from the normal semester we’re going to have,” said Brendan Cantwell, associate professor in educational administration at Michigan State University. “Is it: No students on campus all semester? Do we cycle kids in and out to have fewer residential students? If you bring 50,000 students to campus, the disruption of flipping a switch if we have to go back to online is a lot.”

CMU’s Ampaw agreed. “I don’t see anything that would lead me to believe people would be back on campus in the fall,” she said. “It’s difficult to expect in two to three months (after a statewide lockdown) to expect people to move into residence halls.”

Four of the presidents of Michigan’s public universities are medical doctors, and the presidents of MSU (Samuel Stanley) and Oakland (Ora Hirsch Pescovitz) “are (public) health experts are asking questions in the most conservative way possible,” said Hurley, who represents the university association. “Those questions are being asked, but we’re still taking in intel on a day-by-day basis.”

According to school officials, leaders of college associations and higher ed economics experts, options for the fall include:

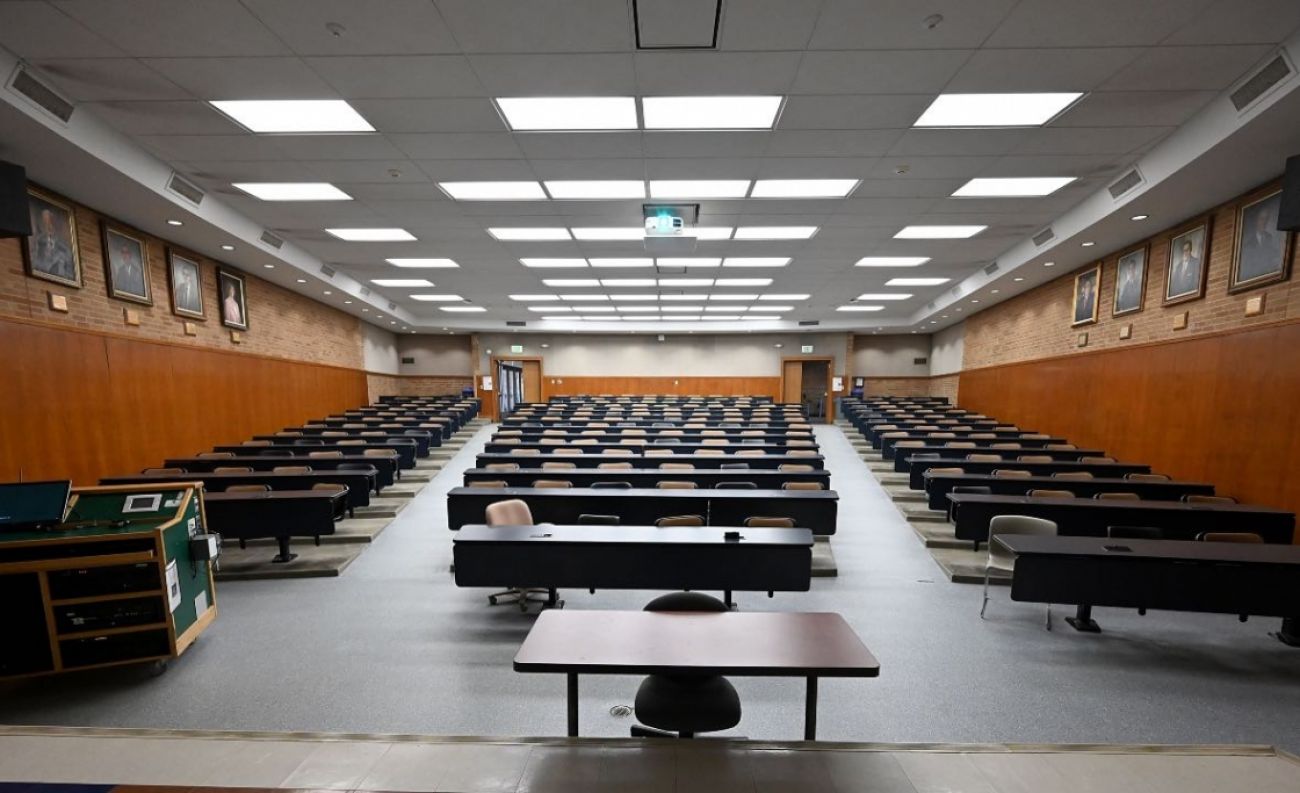

A return to normalcy. Students move into dorms, attend football games and attend classes in large lecture halls. This option offers the least disruption for students and staff, but also has higher health risks because of the lack of social distancing if a vaccine or treatment isn’t developed by September.

Empty campuses. Students take classes online for the full fall semester (or until a vaccine or effective treatment is developed to fight COVID-19), similar to how students are now finishing their current semester online.

This option is the most conservative from a public health perspective, but also carries the largest financial risk and workforce disruption. Universities would lose the revenue from dormitories and meal plans, and may not be able to charge the same tuition rate for online-only classes as they do for traditional in-person education, said Kevin Stange, who studies higher education policy at the University of Michigan.

“If you’re going to college from their parents’ basements, they’re going to be less willing to pay more,” Stange said.

Meanwhile, the cost to colleges to present classes online are similar to or higher than in-person classes, Stange said. Most of the cost of a course is instructor salary, and there are start-up costs for universities converting to fully online classes, such as technology upgrades and in come cases increasing bandwidth to handle so many online meetings. Savings from turning out the lights on classroom buildings is minimal, Stange said.

Enrollment could plummet if students aren’t allowed on campus, as incoming freshmen choose to take a gap year rather than start their college career in the basement of their family home, or students shop around for the cheapest college online course options, Oakland’s Beaghan said.

Some courses, such as chemistry and engineering labs, would be difficult to teach online, Beaghan said.

A full semester of online education would also likely lead to mass layoffs, because of reduced need for employees such as custodians and cafeteria workers, said CMU’s Ampow.

“It’s one thing to convert the last six weeks of a class online (as universities did this spring),” Beaghan said. “It’s another thing to convert an entire semester.”

Begin the fall semester online, with a tentative date of return part way through the semester. This option allows flexibility to adjust with the status of the pandemic.

Students return to campus, but large gatherings are banned.

That could mean no football — or football but no fans in the stands.

A proposal for reopening the state from Michigan Senate Republicans, for example, proposed a ban on sporting events, festivals and concerts until a vaccine comes on the market. Health officials have said a vaccine isn’t likely until sometime in 2021.

“Cancelling the football season, there’s going to be a lot of hesitation about that, but they may not have a choice.”

— Brendan Cantwell, Michigan State University

“Cancelling the football season, there’s going to be a lot of hesitation about that, but they may not have a choice,” said MSU’s Cantwell. Dorm cafeterias could be limited to grab-and-go meals, or a cap placed on the number of students at a table or total students in the cafeteria at a time.

Shuttering dining halls to encourage social distancing may work in East Lansing or Ann Arbor, college towns filled with nearby restaurants. But closing college cafeterias would be disastrous for some small, private institutions in the state, which have one cafeteria for the entire campus and aren’t surrounded by restaurants, said Robert LeFevre, president of the Michigan Independent Colleges and Universities association.

“It is hard to imagine for our campuses to consider campus open and not have dormitories and cafeterias open,” LeFevre said.

Large lecture hall classes with hundreds of students could be shuttered. But the Cornell study found that simply eliminating large classes has little impact on the total contact between students. That being said, lecture halls could be used for smaller classes so students could stay six feet apart.

Oakland University’s Beaghan said his campus hasn’t set a deadline for making a decision about the fall semester. “We’re looking at so many potential scenarios, trying to be ready,” Beaghan said. Michigan universities “are all in the same boat trying to learn from each other.

“Hopefully, the curve flattens and people get better, and we go back to normal,” Beaghan said. “But it’ll never be the same as it used to be.”

RESOURCES:

- Hey, Michigan, here’s how to make a face mask to fight coronavirus

- Michigan coronavirus dashboard: cases, deaths and maps

- Michigan families can get food, cash, internet during coronavirus crisis

- How to give blood in Michigan during the coronavirus crisis

- 10 ways you can help Michigan hospital workers right now

- Michigan coronavirus Q&A: Reader questions answered

- How to apply for Michigan unemployment benefits amid coronavirus crisis

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!