Michigan residents demand better college, career advice

Michigan high school students aren’t getting the college and career guidance they need, risking their future and potentially stunting the economic growth of the state.

And it’s time to do something about it.

That’s one of the major findings of a year-long effort collecting and analyzing public opinion in Michigan on college and career guidance, college affordability and job training.

More than 5,000 Michigan residents voiced their sentiment in more than 140 community conversations held across the state, in scientific polls and online conversations conducted by the nonprofit Center for Michigan. The resulting report, “Getting to Work: The public’s agenda for improving career navigation, college affordability, and upward mobility in Michigan.” released Monday, offers a rebuke to the quality of college and career counseling student receive in high schools today, and calls for more and better-trained counselors.

College and career guidance in Michigan high schools was rated “lousy” or “terrible” by two-thirds of community conversation participants. K-12 educators were only slightly more upbeat than the general public, with 54 percent offering ratings of “lousy” or “terrible.” Only about one in 20 Michigan residents who took part in community conversations or polling rated college and career guidance as “excellent.”

African-Americans were particularly pessimistic, with three out of four unhappy with the quality of high school guidance.

That matters because high school counselors can play a critical role in helping students achieve after high school, which in turn will boost the state’s economy. Michigan ranks in the bottom half of states in adult college attainment. Michigan would need 287,328 more adults to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher just to reach the national average.

Those with a bachelor’s degree earn, on average 64 percent more than those with a high school diploma ($1,101 per week versus $668 per week), according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Just raising Michigan to the national average in college attainment, then, could add $6.8 billion to the state economy.

A Bridge Magazine analysis in March found that while children of middle- and upper-income families were enrolling in college at high rates, low-income students and the children of parents without a college degree weren’t. Raising college attainment levels for the state depends primarily on getting more poor and first-generation students onto campus.

Typically, that job falls squarely on the shoulders of overworked high school counselors.

In Michigan, there is on average one school counselor for every 706 students, one of the highest student-counselor ratios in the nation.

One high school student who participated in a community conversation said, “I had to do my own research because my high school doesn’t do a good job with … career navigation. We just have one counselor for 700 students.”

Another said, “They call them guidance counselors but they’re not; they don’t have time. They’re scheduling, they’re just putting out fires and trying to help students graduate. Rarely are they able to sit down and talk to students about what they want to do” after leaving high school.

Michigan residents overwhelmingly support more and better high school counseling.

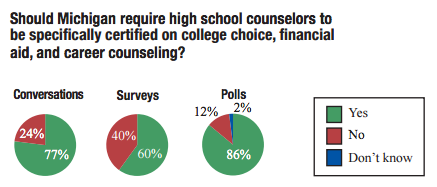

Training counselors to give college advice

One possible fix is to require high school counselors to be certified in college and career advising. That’s not required in Michigan now. Among community conversation participants, 77 percent supported college and career advising certification of counselors; 86 percent in telephone surveys supported the idea.

One school counselor who attended a community conversation said that “It is a counselor’s job to help you find a college and what you want to do. I had no classes that addressed college choice, financial aid and career counseling as part of my education as a counselor.”

A bill introduced in the House in May would require a 45-hour course in college selection advising for all high school counselors. A similar bill died in the Legislature last year.

“By replacing an elective course in the current curriculum with this mandatory class, counselors would be better prepared to help students explore college options,” Patrick O’Connor, past president of the National Association for College Admission Counseling and assistant dean of college counseling at Cranbrook Kingswood School in Bloomfield Hills, wrote in a guest column in Bridge last year.

The bill requiring college advising certification may be considered this fall.

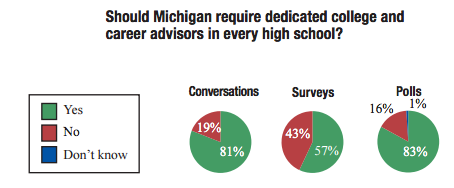

An advisor in every school

A second policy solution admired by Michigan residents is to provide a dedicated college and career advisor in every high school. Eight-in-10 community conversation participants and poll respondents support adding staff specifically for college and career guidance.

Michigan has several growing programs that do just that, which Bridge wrote about in March.

In these programs, graduates from a dozen Michigan universities can sign up to work for two years in mostly rural and low-income high schools in the state, offering college and career guidance. This school year, there will be 82 advisors in 100 schools, under programs at the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, and in a statewide effort called AdviseMI.

Advising corps members received four weeks training and earned $24,000 a year plus benefits in the 2014-15 school year. Most were not education majors. Think of it as a college advising version of AmeriCorps.

“There’s been a resounding response to the AdviseMI program across the state,” said Jacqueline Ruhland, co-director of Advise MI. “A lot of times we see students, particularly first-generation (students whose parents didn’t go to college), who are so overwhelmed they don’t know where to begin. Navigating the college application process and financial aid forms and make college affordable to low-income students can be extremely difficult.

“We’re going to see benefits for the economy moving forward (from placing college and career advisors in high schools),” Ruhland said. “By helping our youth figure out the correct programs, it will help them find a job and thrive and stay in the state of Michigan.”

At $24,000 a year in salary alone, putting a dedicated college advisor in every high school could cost close to $38 million per year.

College and career class

Michigan residents also overwhelmingly support a class for high schoolers that explores career choices and offers guidance on college enrollment. That would be an addition to an already-crowded mandatory curriculum, but many respondents said they felt it would be worth it.

“Even if there are counselors available to help, a lot of students may not seek them out,” said one community conversation participant. “But if you make (career navigation) part of the curriculum, people leaving high school will at least have an idea of where to go for help.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Kylie Horrocks offers college advice to a student at Ionia High School in March. Michigan’s college and career advising is woefully inadequate in most high schools, hobbling the state’s efforts to increase college and career readiness.

Kylie Horrocks offers college advice to a student at Ionia High School in March. Michigan’s college and career advising is woefully inadequate in most high schools, hobbling the state’s efforts to increase college and career readiness. click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge