A Michigan school devoted to innovation. Here’s why others won’t follow.

GRAND RAPIDS – If you want to understand why Michigan K-12 education reform moves at a glacial pace, a good place to start is Kent Innovation High School.

The school, which attracts students from across Kent County, looks more like a business center at a nice hotel than a high school.

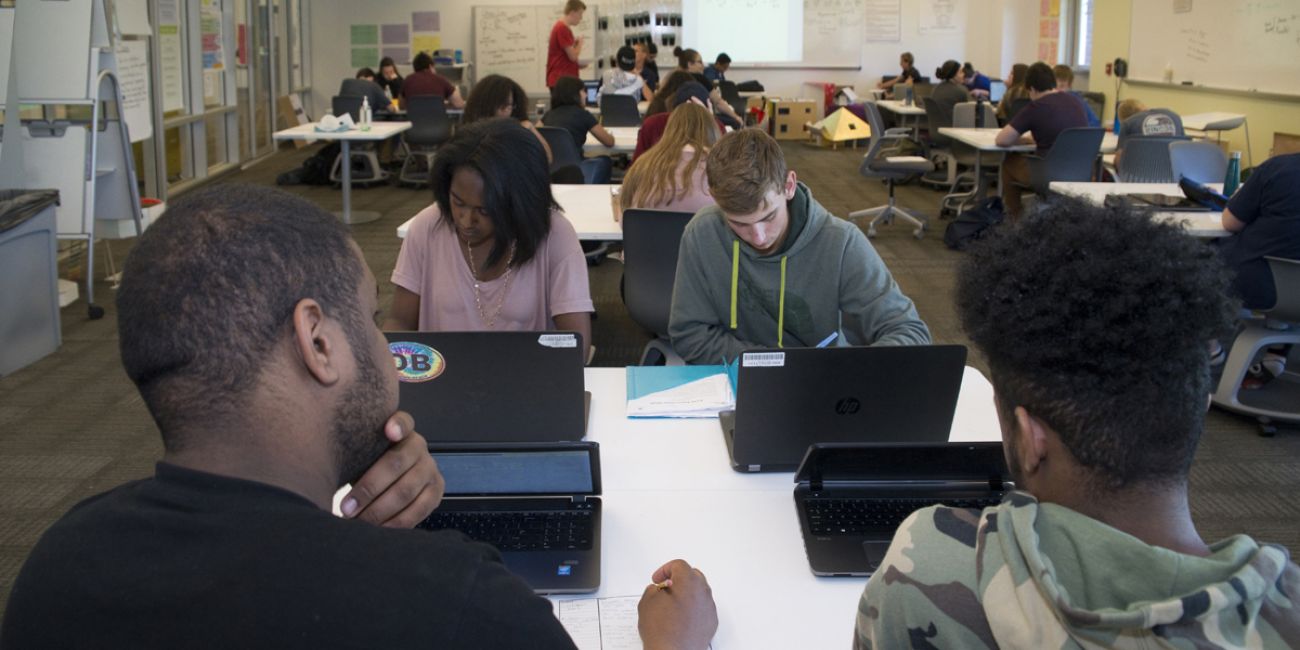

There are workstations in airy common areas, each with plugs for laptops and display screens for presentations. Classrooms have glass walls, where multiple courses are integrated into one classroom – English with social studies, algebra II with physics. It’s not unusual to see a student walking with an open laptop between classes, carrying on a conversation with a sick classmate who is attending through a livestream.

Related Michigan education stories:

There are two teachers in most classes. And they’re not called teachers – they’re “facilitators.” Students work in teams on projects rather than learning individually from textbooks in a system that emphasizes teamwork and critical thinking rather than cramming for standardized tests.

Though standardized test scores from the school are average, students like the system and school leaders in surrounding school districts say there are more students who would thrive in similar schools. But in seven years of its existence as a laboratory school intended to spread education reform practices, no traditional school district in Kent County has copied it.

Reasons have less to do with the education than with money and inertia, education leaders admit. The school’s project-based learning costs 10 to 15 percent more than traditional classrooms, according to the Kent Intermediate School District, which provides educational support to schools throughout the county.

“More superintendents get fired for innovating too much than for innovating too little.” – Dan Behm, superintendent of Forest Hills Public Schools in Grand Rapids

And major reforms can meet public resistance, even among a public that complains about low-performing schools.

“More superintendents get fired for innovating too much than for innovating too little,” said Dan Behm, superintendent of Forest Hills Public Schools in Grand Rapids.

Innovation High’s influence, or lack of it, raises important questions about how public schools measure success, and the willingness of education and political leaders to embrace change, even as Michigan struggles to turn around a flailing K-12 school system.

Related: Detroit finally has money to hire teachers. Good luck finding them.

Related: Sweeping study proposes major changes to how Michigan schools are funded

Innovation High was established in 2011 by Kent ISD to experiment with a different learning system and environment. The concept: a school that was more like today’s real world. Teams of two to four students work on projects that incorporate skills traditionally learned from textbooks. On a recent day, students in a joint algebra II and physics class were building model homes.

“They’re determining how to wire the house, calculating voltage and current,” said physics teacher Gerry Verwey. “They look that up when they need it for their project.”

That type of “just in time learning” takes a lot of advanced planning, but the concepts sink in more because students see how it relates to the real world, Verwey said. “There’s more critical thinking and reasoning skills here” than in a traditional classroom, while still ensuring that students cover mandated academic standards for each subject.

“You have to be OK with learning being messy,” said Innovation High Principal Brandy Lovelady Mitchell. “In real life, we don’t say, ‘Let’s go to this corner and use my math brain.’ It’s all mixed.”

The co-teachers develop projects that incorporate concepts across academic disciplines. “We pitch the project ideas to the students,” Verwey said. “Sometimes they reject them. We want projects they’ll be excited about.”

About 300 students in grades 9 through 12 attend the school, coming by bus from 20 school districts in Kent County. Local districts forward the state funding that follows every student to the Kent ISD, which runs the school.

“I doubt that there’s a single thing as important in my life as coming here,” said junior Lillie Birnie. “I’m still blown away every time I walk in.”

Birnie transferred from a traditional high school during her sophomore year. At her former school, “I was taking chemistry and learning it from reading textbooks,” Birnie said. “I can’t learn that way. It bores me. Here, there’s a lot of hands-on learning.”

Some projects connect them with community leaders. Senior Ravel Bowman said he helped coordinate “food truck Friday” at the school to “highlight entrepreneurship for my marketing class.” He has interacted with so many community and business leaders that he printed his own business cards to hand out, and has “58 connections on LinkedIn.”

Standardized test scores at Innovation High are “middle of the pack,” said Principal Mitchell. The school doesn’t typically attract students making high grades in their home districts. But the project-based, team-oriented learning environment builds soft skills that are worthwhile outside of the classroom, Mitchell said.

For example, students nationwide in schools similar to Innovation High, part of a New Tech system of schools, graduate from high school and stay in college at higher rates than the national average, according to data from New Network Schools.

So why hasn’t the concept spread?

The school was established as a “laboratory school,” said Ron Koehler, assistant superintendent at Kent ISD, so educators could “kick the tires” on different educational concepts. School leaders roundly consider the school to be a success, Koehler said. “But what they found,” Koehler said, “was they didn’t have the resources to recreate it in their own districts.”

Innovation High spends 10 percent to 15 less per student than traditional high schools, a savings that is misleading because the school offers only core classes – no electives, no buses, no sports or extracurricular activities. If the concept were placed in a full-service school, the cost per pupil would be 10 percent to 15 percent more per pupil than current costs at traditional schools, Koehler said.

Most of the additional cost comes from staffing and staff training. Teachers at Innovation High have more time out of class for collaboration and planning, and there is continuing teacher training. There are two teachers in most classrooms, so students can get more individual attention.

Behm, superintendent of Forest Hills, was an early proponent of Innovation High. But even in his district, considered one of the wealthiest in Michigan, Behm has struggled to establish a similar program, which he believes some of his students would benefit from.

Voices of Michigan teachers:

- He loved teaching math in Michigan. Then he quit to manage a Chick-fil-A.

Opinion | Don’t punish schools because Johnny can’t read. Invest in them instead. - Opinion | Want to improve literacy in Michigan? Restore school librarians

- Opinion | It’s time for Michigan to invest in our kids

- Opinion | Michigan Teacher of the Year: 5 ways to motivate students

“The (traditional) secondary school is an outdated model,” Behm said. “We need to move on. It’s a sort-and-select model to determine who is best to go off to college and who goes off to the world of work. We need an experience that is practicing with the types of skills and knowledge base that adults need.”

Behm produced a printout of budgets for the past 10 years. “We’ve had some small increases (in per pupil funding) but we’ve been decimated by inflation,” Behm said. “Each year, when we open the doors, we have to cut something more just to keep up with inflation, let alone having the resources to do something innovative.”

Next year, Forest Hills will open a pilot project-based learning program at Forest Hills Northern High School. It will serve about 40 percent of the freshmen class at the high school, one of three high schools in the district.

It’s taken years for Behm to get that far.

“We’ve got to change this iconic image of high schools,” Behm said. “To change it, you have to disrupt the system. (But) how do you scale it?”

Part of the problem may lay with the way teachers are trained, said Jacque Melin, a former professor at Grand Valley State University’s College of Education. Teacher programs don’t typically give aspiring teachers training in project-based education. “You teach the way you were taught,” Melin said.

She’s placed student teachers at Innovation High, and said she’s been impressed with the “soft skills” that high schoolers attain.

“The kids are much better at critical thinking and teamwork and collaboration and creativity, because they’re given a chance to do those things all the time,” Melin said. “We have to be brave and step out of the box for our future teachers,” Melin said “Otherwise, I think it (K-12 education) will just continue” the way it has.

Change is uncomfortable, but too many students have grown bored with the current, century-old model of students sitting in rows listening to lectures, Behm said.

“When you go to an elementary school, sit in a parking lot and watch the kindergartners get off the bus. There’s a bounce to their step. They’re excited about school,” Behm said. “My deep concern, after 25 years in this business, is that bounce slowly goes away as kids spend more time in the system.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!