Michigan’s college dropout dilemma

It was Wednesday of Welcome Week 2016 at Lansing Community College, and dean of student affairs Tanya McFadden was rushing from event to event. There was food, speeches and a live band.

While students milled about the campus, McFadden had her mind on another group of students. Since 2012, about 2,500 students had enrolled at LCC, come within 15 credits or less of earning a degree, only to leave without a diploma from there or any other school.

That’s the number of near-degree dropouts in just four years, at just one of the state’s 30 community colleges. And that doesn’t count students who drop out of Michigan’s 15 public universities, where only about half of students earn a degree in six years, below the national average of 59 percent.

While Michigan is about average getting students into college, the state does a lousy job keeping them there long enough to earn a degree.

In fact, 1-in-4 Michigan adults 25 or older have some college credits, but no degree, according to a Bridge Magazine analysis of U.S. Census data. That’s the highest college dropout rate in the Midwest. Nationally, Michigan ranks 28th in the percent of high school grads entering college (61 percent), but drops to 41st in graduation rates.

All told, 1.2 million Michigan residents reside in the economic limbo, often over-qualified for high school-level jobs but stopped short of the qualifications needed for degree-required jobs. Hundreds of thousands of these adults are thought to be within a few classes of earning a degree. In some cases, they have enough credits for a credential and don’t know it.

This lack of a degree costs them, on average, hundreds of thousands of dollarsover their lifetimes, and hobbles the economic progress of the state as it scrambles to fill jobs that increasingly require a post-high school degree or certificate.

Some states, such as Virginia and Tennessee, are aggressively pursuing initiatives to lure college non-completers back to campus. But Michigan, already below the national average in adults with bachelor degrees or higher (29 percent, compared with 31 percent across the U.S.) has no statewide program aimed at college dropouts, and no financial aid available for older students enrolling in community college or a public university years after high school.

RELATED: Over 28? You’ll get no student loans from Michigan

‘Low-hanging fruit’

Most experts agree that Michigan needs more college graduates for an economy in which more and more jobs require a degree.

A blue ribbon higher education workgroup in the state released a 2015 report setting a goal of 60 percent of adults with a post-high school credential by 2025. When certificates in trades like computer tech, health care or other fields are counted, an estimated 46 percent of Michigan residents over age 25 now have a certificate or two- or four-year degree (The count of certificate-holders is inexact because of the lack of clear definition of what a certificate is).

To reach its college completion goals, experts say Michigan can’t just focus on 18-year-olds. According to 2014 U.S. Census data, 24.5 percent of Michigan residents between the ages of 25 and 64 had some college credits but no degree, above the national average of 21.5 percent.

If Michigan were just average, 154,000 more adults would have degrees.

Michigan isn’t alone in struggling with high college dropout rates. Nationally, an estimated 15 million people have at least half the credits needed for a bachelor’s degree, according to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, a nonprofit research center that studies the link between education and workforce demands

“Economists call them low-hanging fruit,” said Andrew Hanson, senior analyst at the Georgetown center.

“You have this population, many of whom are underemployed. And it doesn’t take much effort to bring these people up to a post-secondary credential, which by so many measures is the minimum you need to make it into the middle class.”

A degree typically means more money in the bank, it’s as simple as that. The average Michigan college dropout earned 12 percent less than the average owner of a two-year associate’s degree in 2010, according to Census data analyzed by the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems. That equals to a $200,000 income difference over a lifetime. That shortfall is tripled when compared with a bachelor’s degree (more than a $600,000 difference over a lifetime).

The higher the credential, the lower the unemployment rate and the higher the wages, on average, Hanson said

“Part of the value is the sheepskin effect,” Hanson said. “It’s a signal to employers you have certain skills.”

On the bright side, some college is better than none at all. The average income in 2010 in Michigan for those with some college but no degree ($36,000) was higher than for those who stopped with a high school diploma ($31,000). But as the Georgetown research also notes, more than half of college dropouts “are working in high school (level) jobs,” Hanson said. “They went to college, but without a credential, they can’t put anything on their resume. These people have skills. Employers just don’t know about it.”

Hard lessons

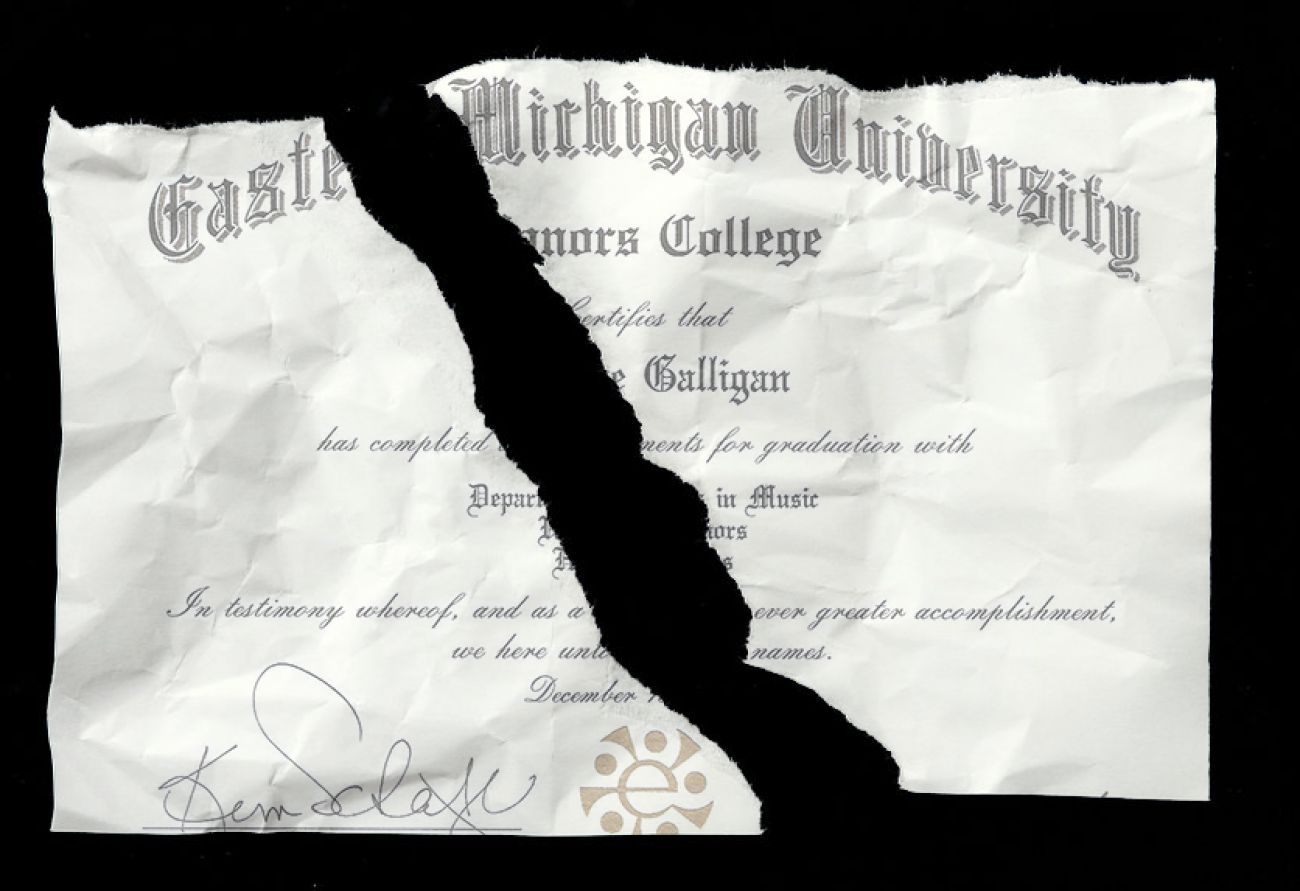

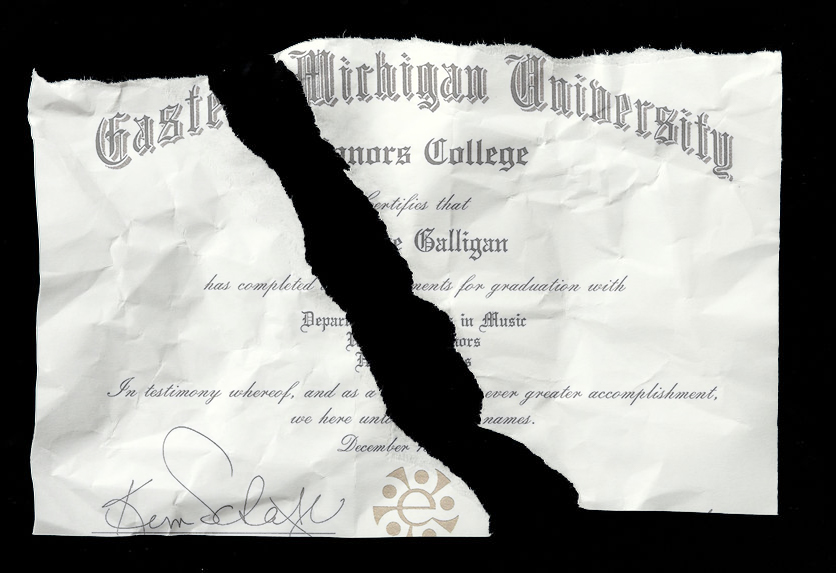

Dean Dauphinais is learning that lesson the hard way.

The 54-year-old Grosse Pointe resident took classes at Wayne State University for two years in the 1980s before dropping out. He didn’t feel he was learning a lot, Dauphinais told Bridge, and he was short on money, so he took a job at a publishing company.

“I thought I was just taking a break” from college, Dauphinais said. “I advanced through the company without having a degree, which kind of took away the motivation.”

He worked there for 24 years. But since Dauphinais left his job three years ago, he’s been unable to find work.

“For a lot of years, I kind of forgot I didn’t have a degree because it wasn’t holding me back,” he said. “But now that I’m back in the job market at 54 years old, I wonder if the lack of a degree is keeping me from getting a job or even being interviewed. It’s almost like a scarlet letter.”

Jobs vs. degrees

Michigan’s college dropouts

Michigan does a good job getting students into college, but a lousy job keeping them there. One in four Michigan adults of working age attended college but didn’t earn an associate’s degree or higher.

Source: U.S. Census, American Community Survey

In some Michigan counties, three-in-10 adults are college dropouts, compared with the national average of 21 percent. Shiawassee and Eaton counties, near Lansing, both have some college, no degree rates above 29 percent. Also north of 29 percent are Oscoda and Alpena counties in northeast Michigan.

The lowest rates of college dropouts can be found in Washtenaw County, home of Ann Arbor (20.2 percent), and the Upper Peninsula’s Baraga County (19.5 percent).

Mike Hansen, president of the Michigan Community College Association, said some dropouts never intend to earn a degree. Instead, many attend community colleges to earn technical training certificates for various professions.

Others are what Jeff Guilfoyle of Lansing-based Public Sector Consultants calls “reluctant students,” taking classes when a recession leaves them unemployed, sometimes paid for by government programs, “because they have nothing else to do.” And then “when they get jobs, they quit” school.

One glaring example occurred in Greenville, after Electrolux closed a factory in 2006 that employed almost 3,000 people. Nearby Montcalm Community College created a solar engineering program almost overnight when solar panel manufacturer United Solar Ovonic LLC announced plans to open plants employing 1,200 people.

“We had at least 60 start the program,” said Rob Spohr, vice president of academic affairs at MCC. “But the company started hiring them before they completed the program. They thought they’d come back to finish, but they were working so many hours they didn’t have time.”

When the solar panel manufacturer packed up and left town in 2012,those workers were left with no jobs and no degree to fall back on.

“When you’ve got a family and a job and working a lot of overtime, it’s tough to go to school,” Spohr said. “The problem becomes, without the credential, when the next recession comes, they’re not as insulated from displacement.

“I tell our students, you’re not getting your degree for today, you’re getting it for your 50-year-old self.”

Finding the right ‘nudge’

The share of Michigan adults who have college credits but no degree has remained stubbornly high over the past decade - 24 percent in 2005, and 24.5 percent in 2014. While studies promote the need to lure adult college dropouts back to school, “there’s a lot of inertia based on the (higher education) system being designed for traditional students,” said Georgetown’s Hanson.

Traditional students – those age 18-24, living in dorms and going to football games on weekends – now make up just half of college students in the U.S. The rest are older adults, returning to campus to increase their earning potential, many of them squeezing in classes between jobs and family responsibilities.

Lynn Blue, vice president for enrollment development at Grand Valley State University, said that in recent years the school has reached out to former students who left the Allendale campus without a degree. About 400 former students returned for degrees, either at GVSU or, through transfer of credits back to a community college, an associate’s degree. Blue characterizes that result as underwhelming.

“If you think about the number of students who stop out at community colleges and universities, it’s in the thousands per year,” Blue said. “I think (we) thought it would be low-hanging fruit, and the fact is, the majority of students don’t see themselves on a degree trajectory.”

But others may just need a nudge to graduate.

That’s the idea behind Project Win Win, a grant-funded initiative among community colleges in Michigan and eight other states that identified and reached out to former students within a few classes of earning a degree, or, in a surprising number of cases, had enough credits for a degree already.

Across the country, 6,700 former students were identified who could be awarded associate’s degrees retroactively based on credits already earned. In Michigan, “there were somewhere like 1,100 or 1,200 students who got their degree in the first phase (of the initiative),” said Chris Baldwin, former director of the Michigan Center for Student Success, an effort run out of the Michigan Community Colleges Association that coordinated Project Win Win here. “About 800 didn’t even have to do anything, just indicated they wanted (the degree).”

Grant funding for the program has stopped, but most community colleges are continuing to audit student records, looking for students who could easily finish a degree.

Credit When it’s Due is a similar grant-funded initiative focusing on former community college students who transferred to four-year universities, only to drop out before completing a bachelor’s degree. Through an audit of student records, Michigan colleges found thousands of former students who, if credits earned at four-year universities were transferred back to community colleges, qualified for a two-year associate’s degree.

Reconnecting with former students has given colleges insights into the barriers to college completion. “We have to continue to parse the 25 percent (with some college but no degree) to truly understand the barriers,” Baldwin said. “Did they come in and get some short-term training and get what they needed? Because of our blue-collar history, there may be some of that.”

Some reasons for not finishing were “shockingly mundane,” Baldwin said. “Some didn’t get a degree because they didn’t want to pay a graduation fee, so colleges are doing away with those fees.

But “the biggest reason students didn’t earn degrees (at Michigan’s community colleges) was because they didn’t take a math class,” Baldwin said.

Something as simple as encouraging students to get math requirements out of the way early can improve completion rates, Baldwin said.

McFadden said Lansing Community College is beefing up its tutoring support system around math classes. “We’re offering 24-hour tutoring and proactive case management outreach,” she said.

McFadden can relate to those math-phobic students. “I started my associate’s degree at 18 and didn’t finish until I was 33 because I was afraid of math,” she said.

“I’m telling you, there is such an opportunity here,” McFadden said. “We’re going to throw the kitchen sink at this problem.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Michigan has a high number of college dropouts, which limits workers’ earnings and makes it difficult for businesses to fill skilled jobs.

Michigan has a high number of college dropouts, which limits workers’ earnings and makes it difficult for businesses to fill skilled jobs. Underwriting for this report was provided by the Michigan College Access Network.

Underwriting for this report was provided by the Michigan College Access Network.