In paychecks, Michigan women have a long way to go, baby

Ann Arbor resident Sue Dean is a notable exception to the rule in Michigan.

With a 2008 master's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Michigan, Dean is a senior operations engineer for an Ann Arbor firm that makes holographic weapons sites. She also earns about twice the $49,449 median full-time wage attributed by census data to men in Michigan in 2013, the latest year available.

That puts her in a better space than most women who work full time in Michigan, who as a group earned on average just 75 cents on the dollar in 2013 compared with men who worked full time, according to a report by the National Women's Law Center. It's less than the U.S. average of 78 cents and places Michigan 41st lowest for women among the 50 states.

“Michigan obviously needs to make some strides,” Dean said. “I still run into people who have the old belief that a woman doesn't need to make as much as a man because she isn't the breadwinner.”

MORE COVERAGE: Hispanic women struggle with just over half the pay of men

A gender wage gap would appear to have sweeping implications for families and children in Michigan, given that 284,000 Michigan families were headed by a single female parent as of 2010, according to the U.S. Census.

According to analysis by the Michigan League for Public Policy, a Lansing nonprofit advocacy group, 28 percent of female-headed households in Michigan lived in poverty in 2012. And more than 40 percent of 315,000 low-income families in Michigan were headed by women.

The pay gap is wider for minority women. According to the report, African-American women earned 66 cents on the dollar compared with men in the state; for Hispanic women in Michigan, the rate was even worse, 57 cents.

Some skeptics

While advocates for equal pay argue that gender gaps should be addressed by lawmakers and industry, critics say that studies showing wide wage disparities can be misleading. Take the statistic that women nationally make 78 cents on the dollar earned by men. That gap, critics note, ignores the fact that women in large numbers tend to go into career fields that pay far less than jobs in top-earning professions.

“The sexes, taken as a group, are somewhat different,” wrote Christina Hoff Sommers, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, in a Daily Beast column in February. “Women, far more than men, appear to be drawn to jobs in the caring professions; and men are more likely to turn up in people-free zones. In the pursuit of happiness, men and women appear to take different paths.”

Sommers noted, for instance, a Georgetown University study of the college majors pursued by men and women. All but one of the majors in the highest-paying fields are dominated by men (In Sue Dean’s major, electronic engineering, sixth in pay, 89 percent of students were male). Conversely, women dominate nine of 10 college majors that led to jobs paying the least amount of money.

Two years ago, a Washington Post fact-checking column took President Obama to task for citing a similar gender study in his State of the Union speech. The Post noted that other studies showed a narrower gap, including one that put the gender gap at closer to 5 cents on the dollar.

“There is clearly a wage gap, but differences in the life choices of men and women — such as women tending to leave the workforce when they have children — make it difficult to make simple comparisons,” the Post column stated.

Financial stress on moms

Whatever the size of the gap, Jane Zehnder Merrell of the Michigan League, said that gender disparities – particularly for low-income female-headed households – is a prescription for ongoing family stress and crisis that can affect multiple generations.

“The first thing is they can't afford housing. When you can't afford housing, you are forced into a situation where you are staying with relatives or friends, who often don't have any more resources than you do.

“Kids suffer,” she added. “What they talk about is toxic stress – the primary caregivers are often stressed themselves. Your primary person in the world is consumed in just trying to survive, not being able to focus on that child. It has long-term impact on academic achievement.”

And while more women in Michigan now have a post-high school education than men (45 percent women, 38 percent men), Zehnder-Merrell said too many women are still concentrated in low-paying jobs with little chance for upward mobility.

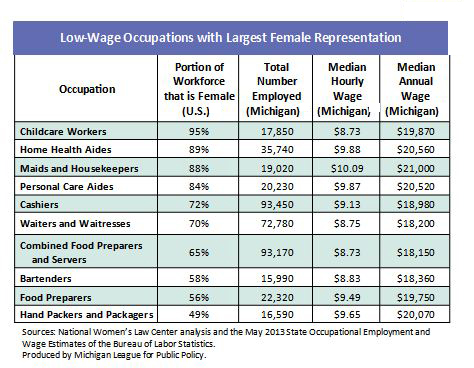

According to analysis by the National Women's Law Center, U.S. women in 2013 held 95 percent of child care jobs, 89 percent of home health aide work, 88 percent of housekeeping jobs and 65 percent of jobs in food preparation and serving. Those jobs had median annual incomes in Michigan of $18,000 to $20,000 – about on par with the 2015 federal poverty level for a family of three.

“There is a mindset that if you get a fast food job at McDonald's, in five years you are going to be able to step into management. There just isn't a (lucrative) career ladder for those jobs,” Zehnder-Merrell said.

Historic gains

A researcher with the National Women's Law Center pointed to historic gains in closing the gender pay gap, progress many trace to passage of the federal Equal Pay Act in 1963, a measure that required employers to pay women the same as men for equal work. But she added that progress seems to have stalled.

“We have made some strides since the Equal Pay Act was passed,” said Kate Gallagher Robbins. “But in the last 10 years, we've seen almost no change in the wage gap. We need to take some further actions. This isn't going away on its own.”

According to the center's analysis, U.S. women earned 60 percent of men in 1965, a figure that climbed to 65 percent by 1985, 74 percent by 1997 and 77 percent by 2002. But it has barely budged since then, standing at 78 percent in 2013.

Robbins credits Michigan lawmakers with raising the minimum wage last year, one of many steps she believes necessary to aid working women and help close the gap (Though there are now efforts in Lansing to ban cities from making minimum wage hikes on their own).

Her organization backs a federal measure that would kick in a steeper increase, raising the minimum wage to $12 an hour by 2020 and indexing it to inflation after that.

Equal pay advocates also back other measures to close the gap:

- The Paycheck Fairness Act, a federal measure introduced in 2007 to give workers tools to combat wage discrimination and bar retaliation against workers for discussing salary information. It is stalled in Congress.

- The federal Equal Employment Opportunity Restoration Act, introduced in 2012, would ensure workers' ability to bring large-scale, class-action lawsuits on pay and discrimination issues against employers. It is given little immediate chance of passage, especially in the GOP-controlled House.

In Michigan, Senate Minority Leader Jim Ananich, D-Flint, backs a measure that would allow Michigan employees to accumulate paid sick leave, and would give workers paid time off to recover from illnesses or care for a sick family member, responsibilities that often are borne primarily by women. While advocates say that could be of critical help to female-headed families, GOP lawmakers in control of the state Senate say the measure would stunt job growth.

Equal pay advocates argue that differences in career choices represent only part of the explanation for why men earn more. As many studies have noted, women typically assume a higher share of family responsibilities than men.

Analysis by the Pew Research Center indicates that women continue to sacrifice career opportunity and pay for such family priorities. That appears to have significant impact on career earnings.

Its 2015 survey found that 39 percent of working mothers said they had taken significant time off from work to care for a child or family member. That compared to 24 percent of working fathers. More than 50 percent of the women said being a working parent made it harder to advance in their job, compared with 16 percent of men.

A report this year by the American Association of University Women found that the gender gap only grows with age, with women earning about 90 percent of what men make until age 35. After that, women fall to making 75-80 percent of men’s pay.

STEM divide

And even though the number of women working in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields has grown, that trend may have stalled as well.

A 2013 Census Bureau analysis of women in STEM occupations noted that progress in employing women has been uneven since the 1970's. It found that employment of female engineers grew from 3 percent in 1970 to 13 percent in 2011, while employment of female computer workers grew from 14 percent in 1970 to just over 30 percent in 1990, before falling to 27 percent in 2011.

“By 2011, women’s representation had grown in all STEM occupation groups. However, they remained significantly underrepresented in engineering and computer occupations, occupations that make up more than 80 percent of all STEM employment female engineers is rising,” it stated.

Minority females are particularly underrepresented in engineering and other sciences. According to the National Science Foundation, black and Hispanic women account for just 2 percent of women working in engineering and science fields in 2010.

Detroit native Amber Spears, a 24-year-old African American, is proud to count herself among that number. She has a 2012 bachelor's degree in engineering from the University of Michigan and a 2014 master's degree in engineering from the University of Texas. She is employed as a civil engineer with NTH Consultants, Ltd., based in suburban Detroit.

Stories of promise

Spears credits her career to exposure as a seventh grader to the Detroit Area Pre-College Engineering Program, a nonprofit program aimed at broadening participation among minority youth in STEM fields. She continued with the program through high school, earning a scholarship to the University of Michigan.

Her career path could also serve as a counterpoint to the argument that women make less because they choose to enter professions that simply pay less. Advocates for equal pay argue that while this may be so, young girls are too often still given the message that certain professions are a man’s province.

“I do think it starts very early,” Spears said. “There is definitely a cultural box you can be put in. A lot of times it boils down to what you are exposed to in your own community.”

Gloria Thomas, director of the Center for the Education of Women at the University of Michigan, said outreach efforts like that the program that benefited Spears need to be expanded.

“There has got to be the will and the desire to make a change,” Thomas said. “It's still unusual for women of color to find a mentor for their career. That all leads to upward mobility and we still have challenges there.”

Dean, the Ann Arbor engineer, took a more circuitous path to her career destination, aided by some encouraging words from a male work colleague. About 18 years ago, she was doing administrative work at an Ann Arbor startup firm, earning about $10 an hour. An engineer at the firm encouraged her to look into engineering. She had only a high school degree at the time.

“He coaxed me. He convinced me it was possible to be a late-in-life student,” recalled Dean, 51. Taking classes at night at first while she continued her job, Dean earned an associates degree from Washtenaw Community College and an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Michigan in 2003.

Dean said her firm, L-3 Communications EOTech, is trying to expand its staff of female engineers. But she noted the firm recently posted two job openings, one for an engineer technician, the other a test engineer. She said the openings attracted about 80 applications, all but four from men.

The jobs went to two men. And for that, she puts some of the blame on women.

“I don't understand why we don't get more applications from women,” Dean said.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Ann Arbor engineer Sue Dean: “Michigan obviously needs to make some strides." (Courtesy photo)

Ann Arbor engineer Sue Dean: “Michigan obviously needs to make some strides." (Courtesy photo)

Detroit native Amber Spears got a head start in engineering through the Detroit Area Pre-College Engineering Program. (Courtesy photo)

Detroit native Amber Spears got a head start in engineering through the Detroit Area Pre-College Engineering Program. (Courtesy photo)