For poor and first-generation college students, ‘I think I can’ is half the battle

Growing up, Abdiel Ramos of Detroit was a honor roll student. Until he failed his first semester in college.

A graduate of Western International High, the University of Detroit Mercy student was underprepared for college math and had poor study habits. He spent too much time playing video games and too little time planning his future. And as the first in his family to go to college, he had no one at home to turn to for guidance on how to handle college life.

But his trajectory changed after he earned a 1.4 grade point average that first semester. The university placed him on academic probation and sent him for help. He was assigned to meet with an “intrusive” professional mentor employed by the university. The mentor met with Ramos regularly, worked with him on time management, assigned him study group appointments and just listened to him.

“My first semester, I didn’t understand the expectations,” Ramos, now 21 and a senior at U-D, told Bridge.

It has been long known that low-income college students, for reasons financial and otherwise, are less likely to graduate. In an effort to improve graduation rates among low-income and other at-risk students, colleges and universities across Michigan are implementing new coaching services to help these students navigate and complete college.

It’s not just about financing college or academics. They work with students, many of them first-generation college students, on everything from how to buy books to finding child care.

Ramos, who is majoring in computer information systems, said he got his cumulative grade point average up to a 3.0 by the end of junior year with the help of his mentors.

“I would not have traded in this experience for anything else, even though it was a roller coaster ride,” he said. “Luckily, I ended up meeting wonderful people.”

This year, as part of its annual “Academic State Champs” public school rankings, Bridge Magazine is honoring public high schools in the state based on the post-secondary success of their graduates. A school is ranked higher if its graduates earned a certificate, associate’s or bachelor’s degree within an average timeframe, or if those graduates remained enrolled and progressing towards a post-secondary degree or certificate.

Within the data, one stark finding: The poverty level of a high school’s student population can be a disturbingly accurate predictor of whether those students are likely to graduate from college or obtain a postsecondary certificate.

Bridge found that at schools with the fewest poor children, nearly 26 percent were considered college-ready as high school juniors (the statewide average typically hovers at 20 percent or lower), 82 percent of graduates enrolled in any higher education program and, four years later, 71 percent had a degree, certificate or were working toward one.

Contrast that with progress of students from the poorest schools: On average just 6.5 percent of these students were college ready, 59 percent had enrolled in a post-secondary program and just 42 percent had a degree, certificate or were working on one four years later.

This is not new information to colleges and universities. In fact, many said they have recognized for years and tried to address the lower graduation rates among students from low-income households or first-generation college students.

The Michigan Association of State Universities, an advocacy group comprised of the state’s 15 public universities, this year plans to hire a director of success initiatives to help universities boost graduation rates. A major focus will be on students from low-income backgrounds, students of color, first generation college students, working adults, and veterans.

On the front lines, Michigan colleges and universities are proactively deploying counselors, mentors, advisors -- they go by different names -- to increase the odds of success. They typically work with low-income students who are often also first-generation college students and usually come to campus with little academic preparation and even less confidence that they fit in. All of which can make it easier to quit when the going gets tough.

The biggest and first hurdle in helping these students is getting them to understand that they, too, belong in college and have what it takes to graduate.

“They battle with self-doubt, or what’s called imposter syndrome. They feel they don’t fit in. They’re wearing this mask and they think they’re going to be found out if they get their first bad grade,” said Rafael Cruz, a professional mentor at the University of Detroit Mercy. “We’re not therapists but we do a lot of cheerleading.”

The Promises

The Kalamazoo Promise scholarship program pays for Kalamazoo’s high school graduates to go to college for free. Since the inception of the Promise in 2005, the Promise increased the percentage of Kalamazoo students earning any postsecondary credential within six years of graduation from 36 percent to 48 percent, according research from the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

But even with guaranteed college scholarships, low-income students still drop out more than others, often because they do not know how to navigate the system, according to staff at Kalamazoo Valley Community College. (Detroit, which has a tax-funded college scholarship program, is also struggling to improve graduation rates among low-income students)

Recognizing that money alone doesn’t solve all problems, KVCC has assigned counselors to specifically help Promise students. They offer help to nearly 500 Kalamazoo Promise students; those who are on academic probation - about 180 - are required to meet with a counselor. If they do not comply, the college will halt the student’s access to the scholarship funds, said Cigi Gamble, a KVCC counselor who works exclusively with Kalamazoo Promise students.

“The college system is literally completely new to them,” Gamble said of at-risk students. “We pull progress reports twice a semester so we can put in preventative measures to help them. It may mean helping them to understand their instructor is someone they can talk to, or that they can go to a study group. And we have meet and greets so they can meet other (Promise) students and build a sense of community.”

Similarly, the Detroit Promise Zone scholarship this year assigned coaches to its students at the five community colleges in metro Detroit. The Detroit Promise is a privately funded program that will be eligible for tax support in 2018 and ensures that all Detroit high school graduates get access to a free community college education. A “last in” program, it pays tuition costs that are not covered by a student’s financial aid grants.

The Detroit Regional Chamber of Commerce, which administers the Detroit Promise, is piloting a student coaching service this year modeled after the intensive advising of the “ASAP” program at the City University of New York (or CUNY), which doubled its three-year graduation rate for low-income students from 22 percent to 40 percent.

Detroit Promise scholarship recipients get a $50 gift card each month if they don’t miss any appointments with their college counselor. The results from the coaching will be studied and compared with a control group of Detroit Promise students who are not getting the counseling.

The Detroit Scholarship Fund, the privately-funded predecessor to the Detroit Promise, started in 2013 and data showed that college graduation was a problem even when college funding wasn’t, said Greg Handel, vice president of education and talent programs at the Detroit Regional Chamber. Only about 20 percent of the first group of Detroit Scholarship recipients finished community college within three years, about the average for low-income students, Handel said.

The Detroit Promise wants to double its graduation rate like New York did, he said.

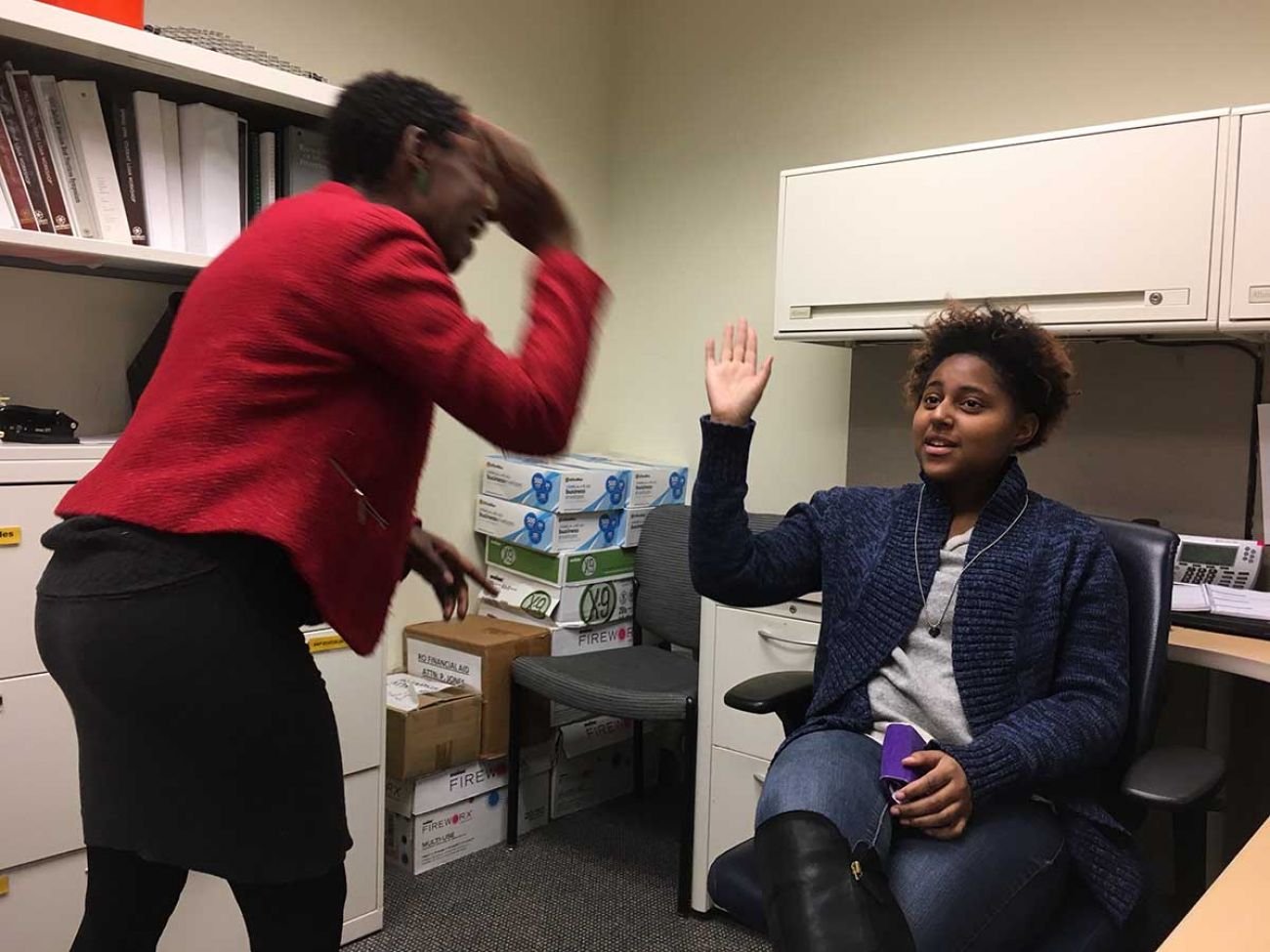

Ashley Robinson, the Detroit Promise campus counselor at Schoolcraft and Oakland community colleges, meets with about 50 promise students. Another 36 have not re-enrolled this semester.

“I call them and call them,” Robinson said. “Ask them what they need. A lot of their problems have to do with financial aid. They don’t know what to do. But once I know that, I can use my resources here to solve their problems. I’m a professional stalker.”

Monique Whittaker, 18, a first-year OCC student from Detroit, said Robinson has helped her figure out issues with transportation, scheduling and financial aid in addition to being a trusted listener.

During a recent appointment, Robinson and Whittaker shared high fives to celebrate Whittaker’s hopes for being chosen to give a speech about the Detroit Promise. But news that Whittaker, who’s studying fashion apparel and marketing, didn’t turn in an art project on time earned a stern side-eye from Robinson. And advice about how to follow-up with the instructor. They plan to do an arts and crafts project called “a vision board” to plan out Whittaker’s goals at an upcoming meeting.

“Ashley is my go-to person. With Ashley, I’m venting and finding solutions,” Whittaker said. “She helped me to think positive. Instead of always thinking, ‘What if this goes wrong?’ Now I think, ‘What if this goes right?’”

“If Ashley wasn’t here to help me, I don’t think I would still be in college.”

Bridge Staff Writer Mike Wilkinson contributed to this report.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!