Students to University of Michigan: Stop funding Detroit evictions

University of Michigan students, staff and faculty on Thursday asked the Board of Regents and President Mark Schlissel to divest from a real-estate firm whose investments have led to evictions in Detroit.

The group of about a dozen appeared before the regents one week after a Bridge Magazine article detailed the university endowment’s $30 million investment in the Detroit Renaissance Real Estate Fund, a company owned by Corey Hanker and Jordan Friedman. They own a separate firm, FDR, that bought 112 homes at Wayne County’s tax auction homes last fall, 47 of which were occupied at the time of foreclosure. The company since filed evictions on 20 of those homes.

That has led to complaints from students the university’s investment in Detroit is doing more harm than good. Two students made public comments at the meeting, urging the board to reconsider its investment.

Related: The University of Michigan bet big on Detroit. Now come the evictions

Related: Opinion | U-M’s investment in Detroit is helping us improve Detroit, not evict people.

“This $30 million investment undermines the public mission of this university and the president’s agenda to alleviate poverty in Detroit,” said Alexa Eisenberg, a U-M doctoral candidate and a board member with the United Community Housing Coalition, Detroit’s principal tax foreclosure prevention nonprofit.

“This investment – in a direct and irrevocable way – threatens the stability of Detroit families and promises to inflict further damage to the city’s neighborhoods,” she said.

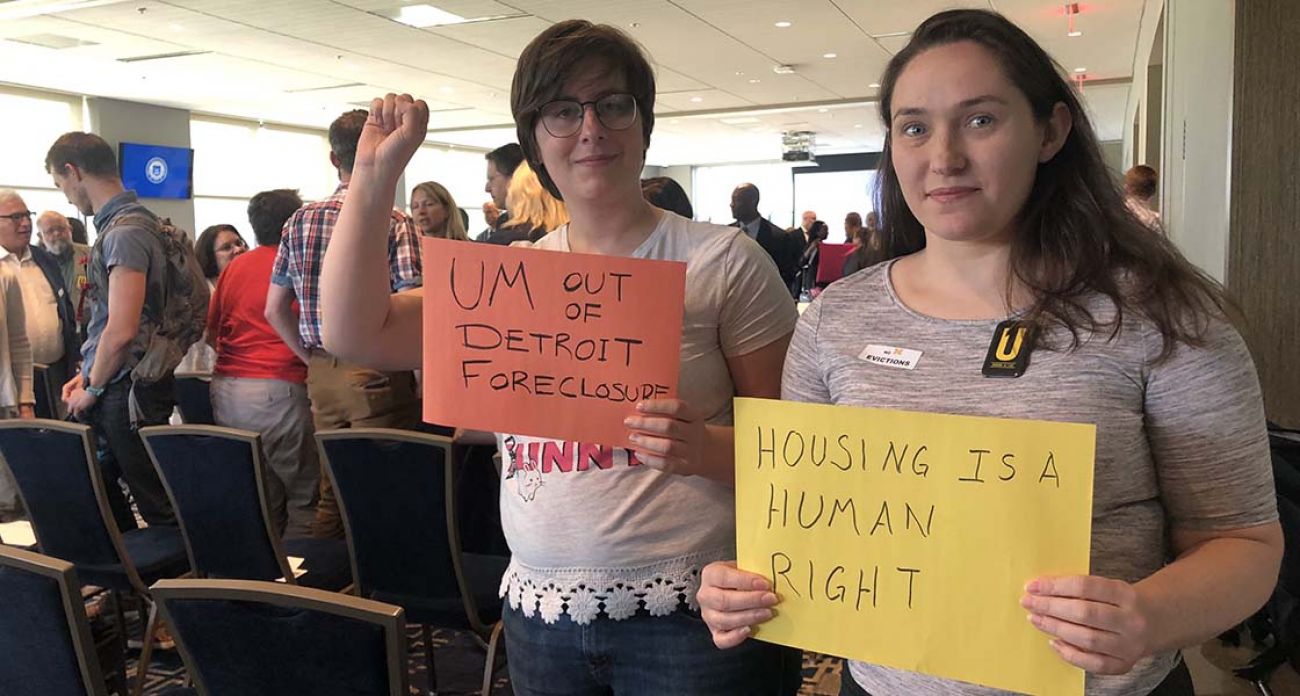

The group of U-M students and staff wore stickers that read “No M Evictions” and carried signs with messages including “UM out of Detroit Foreclosure” and “Housing is a Human Right.”

“What we’re hoping to do is send a strong message to Schlissel, to the regents and the rest of the university administration that investing this amount of money in a company that is profiting by evicting Detroiters from their homes is just totally contrary to the university’s public mission,” said Joel Batterman, a U-M doctoral student in urban and regional planning, who also spoke at the meeting.

University officials did not respond to the students during the meeting, but officials met with them afterward to discuss their concerns and the Bridge article. In response to a request for comment from Bridge, university officials sent a statement about its endowment that mentioned the university has "invested significantly in Detroit and the metro area," but did not directly address the Fortus investment.

Last week, Schlissel said Detroit neighborhoods could benefit from more outside investors, telling Bridge an argument could be made that “the dislocation of a certain number of people in return for investment in decaying housing stock is part of the pathway to making the city a better place to live.”

Friedman told Bridge after the meeting that the auction-acquired properties are a “very small part” of the company’s portfolio in Detroit. The company typically avoids buying occupied homes, he said, and only moved to evict after occupants illegally entered their property after purchase and numerous attempts to work with them failed.

“We're very, very long-term committed to this city,” Friedman said. “We're not trying to make money quickly. Our only concern is being good to Detroit. And we really pride ourselves on our community involvement and really making sure we're doing right by the neighborhoods and the people there.”

Friedman said he hopes to start a conversation with Detroiters, U-M students and staff about the company’s investments.

“I’d love to have a dialogue and learn more, and keep this conversation going, because it is an important conversation,” Friedman said. “We’re sensitive to the issues, we’re aware of these issues.”

It is unclear why and how the university endowment fund decided to invest in Detroit real estate.

Lindsay Calka, an undergraduate student at U-M, spent July visiting tax-foreclosed homes in Detroit with her peers, and warning residents of potential evictions. She is part of a university program that allows students to take classes on Detroit and complete an internship at a non-profit, grassroots organization in the city.

“It kind of made us really sick,” said Calka, speaking of the investment.

“Here we are, students doing this, and we find out that our university is potentially funding the companies that are buying these homes and causing evictions.”

Calka said she hopes she and maybe even the university can make a difference.

“I came here idealizing the university. It’s a force to be reckoned with...for making change and having social impact. I still have this hope that it can be a force for good,” Calka said.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to better reflect the University of Michigan's response to students and Bridge Magazine.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!