‘Zero tolerance’ school reforms hit resistance in Michigan

Eighteen months after state education leaders urged reforms to “zero-tolerance” discipline policies, an analysis of two large Michigan school districts found that they still impose disproportionate numbers of suspensions and expulsions on minority students.

And while some districts have installed measures to address that issue, critics say too many students are still being lost to expulsion or suspension. A growing chorus of critics says zero-tolerance measures, while well meaning, often fail to curb student misconduct, while paving the way to higher rates of dropouts and incarceration down the road.

“Michigan mandates expulsions that pretty much go beyond any other state in the country,” said Peri Stone-Palmquist, executive director of the Ypsilanti-based Student Advocacy Center of Michigan, a nonprofit student rights organization.

She cites a body of research showing “that the students who have been expelled, the students that get in trouble, are often the ones that need the most help.”

A 2009 report by the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan found that districts across the state meted out a greater share of discipline to minority students, thereby increasing the odds that suspended or expelled students would drop out of school or wind up in prison or jail.

It mirrored national findings for 2009-2010 by the U.S. Department of Education that black students were 3.5 times more likely to be suspended or expelled than white students.

Follow-up analysis this year by the ACLU of two urban districts – Ann Arbor and Grand Rapids – revealed similar results.

In Ann Arbor Public Schools in 2012-2013, black students comprised 14 percent of the student body but 50 percent of out-of-school suspensions, the ACLU found through data collected under the Michigan Freedom of Information Act.

In Grand Rapids Public Schools, black students comprised 36 percent of the student body but more than 60 percent of the 3,511 suspensions in the first semester of 2012-2013, the study found. White students – 22 percent of the student body – accounted for 11 percent of suspensions.

Acknowledging the issue, the State Board of Education in June 2012 issued a recommendation that districts reconsider their approach to discipline.

“Researchers have found no evidence that zero-tolerance policies make schools safer or improve student behavior,” the board stated. “In fact, studies suggest that the overuse of suspensions and expulsions may actually increase the likelihood of later criminal misconduct.”

A 2005 Texas study concluded that the single greatest predictor of youth incarceration was a history of school discipline. Another Texas study found that one-third of all youth in a juvenile facility had dropped out of school, and that 80 percent of adult inmates were high school dropouts. A 2011 national academic study also found that black and Hispanic students received harsher penalties for the same offenses as white students.

The Board of Education statement added that suspension or expulsion “should be reserved for the most serious infractions, and not used as a means of discipline for minor occurrences.”

It also noted the black and Hispanic students and students with disabilities “are suspended or expelled in rates disproportionate to their population.”

How Michigan got tough

The federal Gun-Free Schools Act of 1994 mandates that students who bring guns to school be expelled for at least a year.

Michigan went further. Beginning with legislation that took effect in 1995, Michigan requires permanent expulsion for students who bring a dangerous weapon to school, commit arson or criminal sexual conduct. Student must be expelled for at least 180 days for physically assaulting a school employee or volunteer.

To be sure, grim newspaper headlines in the years since are continual reminders that school safety is a legitimate concern. In 1999, two students at Colorado's Columbine High School killed 12 students and a teacher before committing suicide. In 2012, a lone shooter killed 20 elementary school students and six adults in Connecticut before killing himself.

But reform advocates say that well-intentioned zero tolerance policies make schools no safer, and ultimately harm too many students through inflexible discipline measures.

Some Michigan examples:

· An eighth grader named Mike was kept out of school for 180 days in 2012 for possession of an Airsoft gun, a replica gun that fires plastic pellets. According to the center, he was left with no viable alternatives for education.

· A 12-year-old boy named Wyatt was expelled for 180 days in 2012 when a school bus driver saw him playing in the dirt with a knife he had found in an alley near his home.

· A Detroit high school sophomore was suspended in 2007 for bringing a small device to school to shape eyebrows that contained a razor-like blade.

· In March 2013, a Farmington Hills high school freshman (see accompanying article) was expelled for 180 days after he and a teacher wrestled over a paper another student had taken from his school folder. He was removed from school in handcuffs and faced assault charges that were vacated in exchange for a no-contest plea in December. He now attends a different school. The district superintendent expressed frustration with the zero-tolerance law in that case.

“As sad as that case is, it's hardly the worst I've seen,” said David Fancher of the ACLU of Michigan.

The Michigan Department of Education keeps no statewide records on suspensions. It recorded 1,823 expulsions in 2010-2011, 1,893 in 2011-2012 and 1,796 in 2012-2013.

Kyle Guerrant, director of the state Office of School Support for the Michigan Department of Education, said districts are increasingly aware it is an issue they have to address.

“The way it is now we are losing millions of hours of instruction to…suspensions and expulsions. Obviously that has a far-reaching impact,” he said.

One advocate of reforming the state’s zero tolerance law said the issue is not whether schools face serious student behavior issues - but rather how they deal with this behavior.

“It is sometimes portrayed as an issue of uncaring and biased schools and administrators,” said Bill Sower, founder and director of The Christopher and Virginia Sower Center for Successful Schools, a nonprofit education reform organization based in Plymouth.

“The fact is, schools are facing a serious problem with misconduct.”

He cited a national survey by Public Agenda, a New York-based nonpartisan research organization, that found four in 10 teachers report spending more time trying to restore order in class than they do teaching.

“Then we are left with the dilemma, if we are not going to be punitive, what are we going to do?”

A promising alternative

Sower advocates an approach to discipline known as “restorative justice,” modeled after measures that originated in the 1980s in New Zealand.

“This is not kumbaya. This is a higher-level authority,” Sower said.

Under this approach, a trained mediator convenes a group that includes the offending student, the teacher, those harmed in the incident and the parents or siblings of the student. The idea is to encourage students to accept responsibility for their actions and learn from the experience.

“Kids have to come face-to-face with the people they harmed. This is aligned with conventional discipline,” he said.

Sower said it has proven to reduce suspensions and expulsions, but is only being used in a handful of Michigan districts.

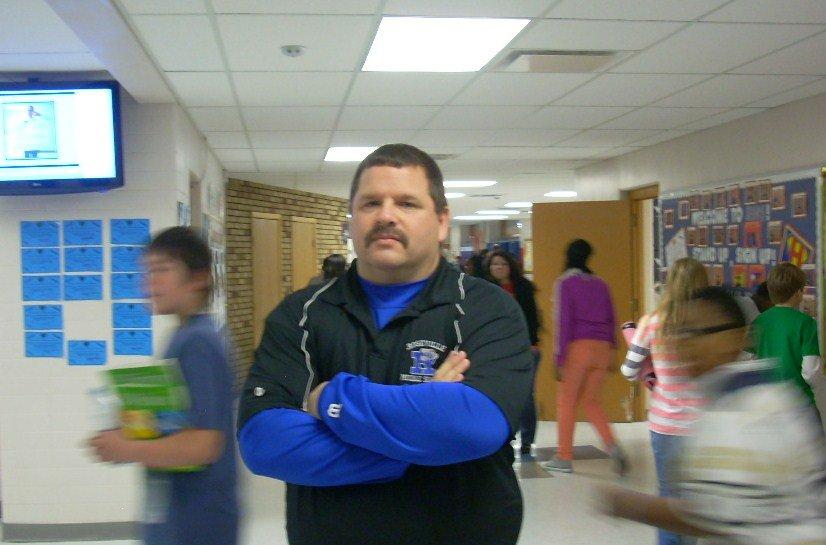

Dave Rice, principal of Roseville Middle School in Macomb County, was skeptical when the school considered adopting a restorative justice program during the 2011-2012 school year.

“I resisted it. I will flat out tell you that,” Rice said.

It was put in place in the fall of 2012, with a full-time facilitator and aide. Critical to its success, Rice said, teachers have bought into the approach.

“We have seen results all over the place,” Rice said.

In 2011-12, Rice said, the school expelled 14 students. It expelled 11 the following year and thus far this year, just one.

“Community involvement is way up here. Parents are calling, saying, ‘I hear you have peace circles. Can I get my kid involved in a peace circle?’

“The kids are not turning into angels. But what they are doing is at least thinking more.”

Jeanice Kerr Swift, superintendent of Ann Arbor Public Schools, acknowledged that disproportionate minority discipline remains a challenge in her district. But Swift cited progress, spurred by the hiring this school year of four specialists who work with students with behavior concerns.

The district cut suspensions from 557 in 2011-2012 to 361 in 2012-2013, including substantial reductions among black and special needs students.

“We have a lot of work to do. We are the first to say that. But this strategy is working very well,” she said.

State Sen. Rebekah Warren, D-Ann Arbor, said it is time to scale back provisions of Michigan's zero-tolerance law. She intends to introduce legislation in 2014 to give more discretion to local school districts in how they discipline students.

“I think we are seeing that (zero tolerance) is an overreaction. It allows for absolutely no flexibility. We need answers for those kids.”

While Warren said she hasn’t yet gauged the level of support for reform of zero tolerance, she said “some of our Republican colleagues are interested in the issue as well.”

But Sen. Phil Pavlov, R-St. Clair Township, chairman of the Senate Education Committee, said he sees no pressing need to change the law.

“When I reviewed this, it was clear the school board does have a lot of discretion in these issues,” he said. “There is always a balance you want to make.”

Pavlov said he recently consulted with the superintendent of Port Huron Area Schools about the issue. “In his 14 years, he said he hasn't seen anything to cause him to reach out to the legislature for more control,” Pavlov said.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Dave Rice, principal at Roseville Middle School in Macomb County, was skeptical of alternatives to zero tolerance discipline policies. He’s now a big supporter of his school’s “restorative justice” approach, which he said has cut expulsions and gained buy-in from teachers and parents.

Dave Rice, principal at Roseville Middle School in Macomb County, was skeptical of alternatives to zero tolerance discipline policies. He’s now a big supporter of his school’s “restorative justice” approach, which he said has cut expulsions and gained buy-in from teachers and parents.