A Detroit bathhouse cleans up its act. Welcome to the Schvitz. (Slideshow)

The first punches had yet to be thrown in the heavily hyped Floyd Mayweather-Conor McGregor prizefight last month when Paddy Lynch looked around his newest project and saw a glimpse of what could be.

It was just a few months after he borrowed against the equity in his historic Detroit mansion and paid $160,000 cash for the Schvitz, a dilapidated, notorious and history-rich steam bath and club in the city’s North End neighborhood. Fight night was a fundraiser for its renovation, with the pay-per-view match displayed on screens on two of the club’s three levels. About 150 people paid to attend. Wearing everything from spa robes to Saturday-night heels, they mingled from the basement steam room to the main-floor dining room and the recently opened second-floor ballroom.

“All those people, enjoying everything it has to offer,” Lynch said of the crowd. “That’s what I want for it."

The Schvitz was born in an earlier era, when hot running water was less common, and working people needed a place to get clean, relax and escape. It’s being reborn in a neighborhood with many problems and much potential. Detroit’s real-estate comeback is pushing north from the central city. Lynch’s handsome house is only few blocks away, but the one across the street from the Schvitz on Oakland Avenue is burned; a nearby church is active, but with some boarded windows. The neighborhood could use some more viable businesses, but the last thing Lynch wants is to be just another yuppie gentrifier.

It will be a tall order, he acknowledges. The building is nearly a century old, its plumbing not much younger, its reputation falling somewhere between colorful and infamous. It won't be cheap; the current budget of $250,000 will do a lot, but not everything. Cash flow is a big question mark.

But the Schvitz is also a place its regulars have kept running for decades, one they feel connected to in ways they express in near-religious terms. It’s a place of purification, of cleansing, a sanctuary where troubles are exorcised in puddles of sweat. It’s a hard place to turn your back on.

Alan Havis, one of Lynch’s two partners, has been coming to the Schvitz for years and is typical of the old guard. His patronage began in 1981, when he was attending law school downtown and began meeting his father and great-uncle there on Thursday nights.

“It’s not only a social thing for me, but it’s the thing that I do for myself that lets me do the other things I do,” said Havis, 57, of his weekly visit.

“I can sweat it all out, get my head together, and (work hard) for another week, until I can get back there again.”

If Lynch can take that core of devotees and build a larger clientele around them, he said, he can do good not only for the business, but the neighborhood and maybe even the city itself.

The Schvitz reopens Oct. 1, with an open house for old and new customers, neighbors and the general public. It’ll still be a work in progress, Lynch concedes. But in some ways, it’s always been one.

A steamy history

Schvitz is a Yiddish word. It means sweat.

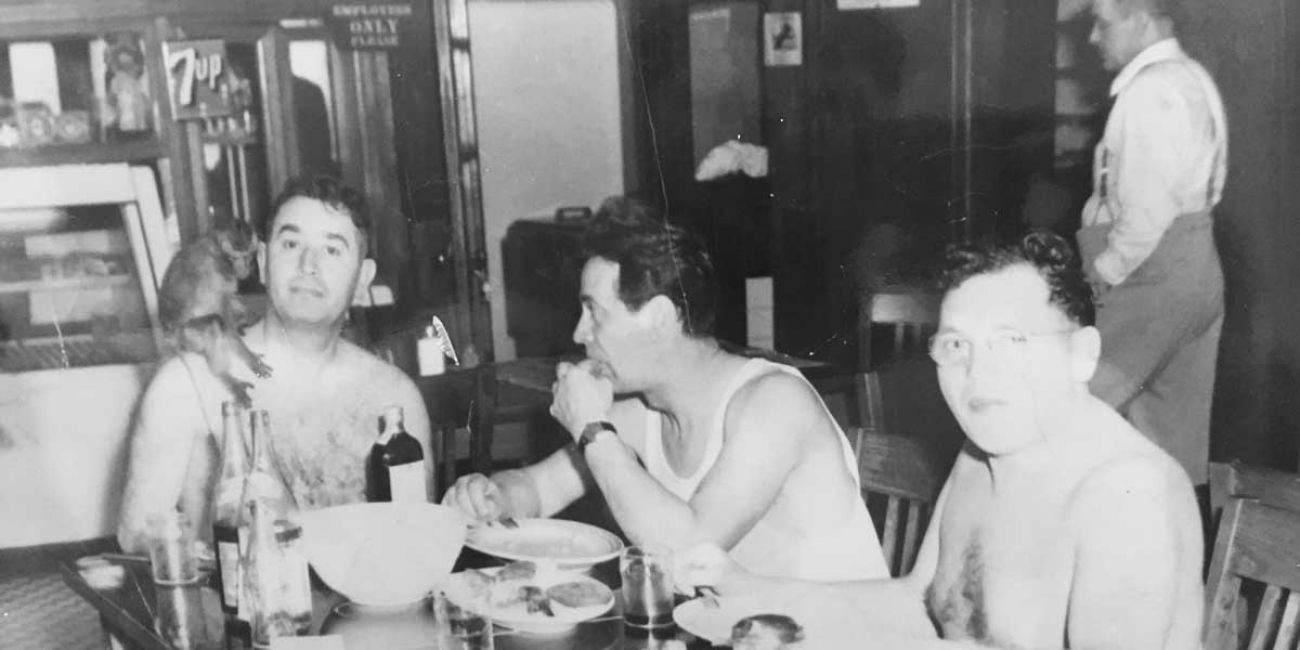

The Schvitz’s founding is rooted in Judaism; it opened in 1918 as a Jewish cultural and community center for the North End neighborhood. The basement was dug out later, when the steam room and a cold-water pool were added; tilework on the pool deck says 1930, and it was sometime around then that its clientele grew to encompass the Purple Gang, the fearsome criminal mob of the city’s Prohibition era. The Schvitz was run by members of the Meltzer family from the 1930s to the mid 1970s. Rick Meltzer, whose father and grandfather were the proprietors, said during that time it was largely a men’s club – ladies-only on Wednesdays – that served up steam, relaxation and big meals afterward.

“My dad always said the Purple Gang guys hung out there, but they didn’t run the place,” Meltzer said.

That job was done by Eugene “Toots” Johnson, who was said to have stopped by looking for work in 1929, started digging the basement project with an offered shovel, and never really left until he died in 1987.

By the late ‘70s, the club was following the decline of the city. It was sold to a succession of owners and entered an era many modern Detroiters have at least heard about, that of the infamous “couples night.”

Couples night, or nights, were Fridays and Saturdays, when male-female couples paid $75 to have the club to themselves for open sexual activity. For decades, the Schvitz had a binary identity; during the week, it was a place for men, many of them Russian or eastern European devotees of steam, to sweat and socialize in the banya, and on the weekends, a place for swingers.

It was the sex, more than the mobsters, that gave the place its shady reputation, Lynch said. After the partners closed the deal in March and got the keys, couples night was the first thing to go.

“The phone rang for weeks,” said Jessie Nigl, the third party in the new management, who will supervise its daily operation. One day she let another employee answer, she said, lacking the heart to “disappoint another displaced swinger,” and overheard her telling the caller, “This is a de-sexualized space now.”

“We thank those people for helping keep the lights on for many years,” said Lynch. “But it’s time for something new here.”

What Nigl, Lynch and Havis want to build in its place is a hybrid Schvitz and spa, open to men some days, women on others, with co-ed days – swimsuits required, no sex tolerated – in between. On weekends, it’ll be available for private events. Havis hopes to rekindle the tradition of fathers bringing their sons and more family-friendly activities. A Sunday ladies’ brunch potluck was attracting good business before the Schvitz changed hands, so the partners hope there’s a female customer base ready for communal sweating, too.

The owners plan to build a separate dry-heat sauna, offer conventional spa treatments – massage and barbering for men, massage and skin treatments for women – and eventually reopen the kitchen. The unsavory history will be part of the allure.

“This was a wild place, and we embrace that,” said Havis. “The sex, drugs, gambling, Purple Gang – we embrace it, but call it folklore. We’re about therapy, not sexuality.”

Purging through the pores

Lynch, 33, grew up in West Bloomfield, a third-generation scion of the Lynch & Sons funeral-home business, where he makes his living at the family’s Clawson location. A graduate of Brother Rice High School and Boston College, he has the idealism of a Catholic missionary and the social network that decades of funeral service affords a family. (His uncle, Thomas Lynch, is a poet and essayist, and the subject of the 2007 “Frontline” documentary “The Undertaking,” as well as a creative inspiration for the HBO series “Six Feet Under.”)

Lynch has been coming to the Schvitz for five years. He’d been through a rocky period after college graduation and a searing stint in Haiti, doing service with the Little Brothers of the Incarnation, a monastic order of priests. The work, with AIDS patients and desperately poor Haitians, left him depressed and medicated.

Going off antidepressants wasn’t easy, especially in his line of work.

“Funeral homes are sad places and it’s not easy work, and going to the Schvitz one or two days a week was my place of purification,” he said. He made friends, and started feeling better. “I was surprised by the atmosphere, of men sweating in the basement in this obscure part of the city.”

But he said it was Nigl who opened his eyes to what the Schvitz could become. Nigl took Lynch on a trip to the 10th Street Baths in New York City, a similar facility now enjoying a renaissance among millennials.

“It really showed me what we could do,” Lynch said. “That we could make this place into something far better, for more people.”

When they got home, they contacted Havis and began negotiations to buy it.

Since they took possession in March, the building has continued to reveal itself. The new owners tore up ancient carpet and tore down drop ceilings, exposing original tile and pressed tin.

Opening some bricked-over windows improved the air quality. But the biggest revelation was under the floor in the swingers’ TV room – a mikveh, the ceremonial bath used by observant Jews for purification purposes.

Rabbi Yisrael Pinson, executive director of Chabad of Greater Downtown Detroit, examined it for authentication purposes, and said he believes it dates from the building’s original construction. It had a basin to collect rainwater, as a kosher mikveh must have a natural water source. It was close to an exterior door, so that women could come in and use it without passing through the men’s area. And it had the traditional six steps to the bottom.

“Every Jewish community needs to have a mikveh. It makes sense that as we’re rebuilding the Jewish community (in Detroit), we should build a mikveh,” Pinson said. He wants to start fundraising to restore it, which would make it the only one in the city.

Such details suggest the building could one day gain historic status, making it eligible for grants or low-interest loans, Nigl said. In the meantime, owners want to make the facility more open to neighbors.

Lynch is considering a lower neighborhood-resident admission charge (currently $25), converting an unused lot to a garden tended by the Oakland Avenue Urban Farm, and other diplomatic gestures.

Lynch said a neighborhood resident who grew up there told him her mother had always instructed her to walk on the other side of the street when passing the building, “because it was full of mean white men.” He wants to change that perception.

A big step may come in the spring, when the University of Michigan’s University Musical Society will take over the basement space to produce “Bubble Schmeisis,” a one-man play by Nick Cassenbaum, with live klezmer music.

“They’re going to build a stage over the pool,” Lynch said. “It’s a play about a schvitz that will actually take place in the Schvitz.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!