Diego, Frida, and my grandfather in Depression-era Detroit

This article also appears in a special edition of Detroit Metro Times , the city’s alternative weekly. The publication is struggling to survive the economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic. BridgeDetroit reporter Louis Aguilar is among the local writers and other artists who have donated works for the special edition. The artists were asked to share what is giving them hope during the pandemic.

If Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo had their way, I’d have been born in Mexico, rather than Detroit.

In Depression-era Detroit, the two glamorous Marxists tried to convince my maternal grandfather and his brothers to leave America to create a workers’ utopia in Mexico.

My grandfather and his brothers, all railroad workers, said no – and stayed to endure the economic freefall, and to build a future for their children, and their children. I am grateful.

We read and hear the word depression a lot right now – both in emotional and financial terms. I’m drawing strength from conversations my relatives had with the genius artists long ago.

The exchanges happened around late 1932 and early 1933. The world was in a terrible mess ever since the stock market crashed Oct. 29, 1929. No one really knew when, or if, it would get better.

Detroit, a factory boomtown in the early 20th century, was slammed harder than most places in the U.S. The city’s jobless rate was 50 percent, double the national level. Two-thirds lived in poverty. There were massive street protests demanding jobs and aid from the government and automakers.

Amid this bleakness arrive the superstar artist Rivera and his wife, a then-unknown Kahlo. The Mexican artist had gained international acclaim for his murals and paintings that celebrated the common worker, among other thing

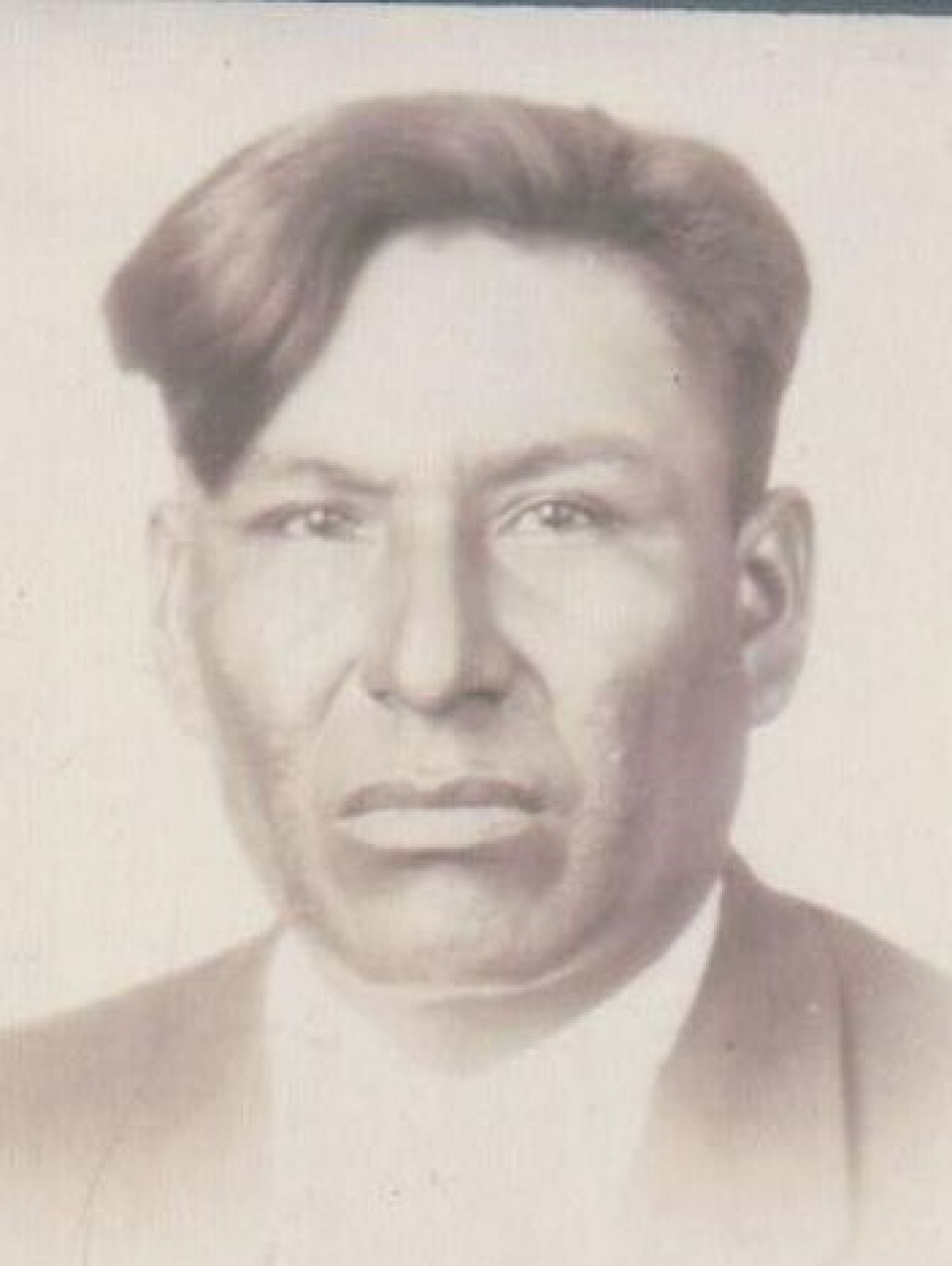

My grandfather, Antonio Martinez and his two brothers, Francisco and Jose, were Detroit working men living in Corktown.

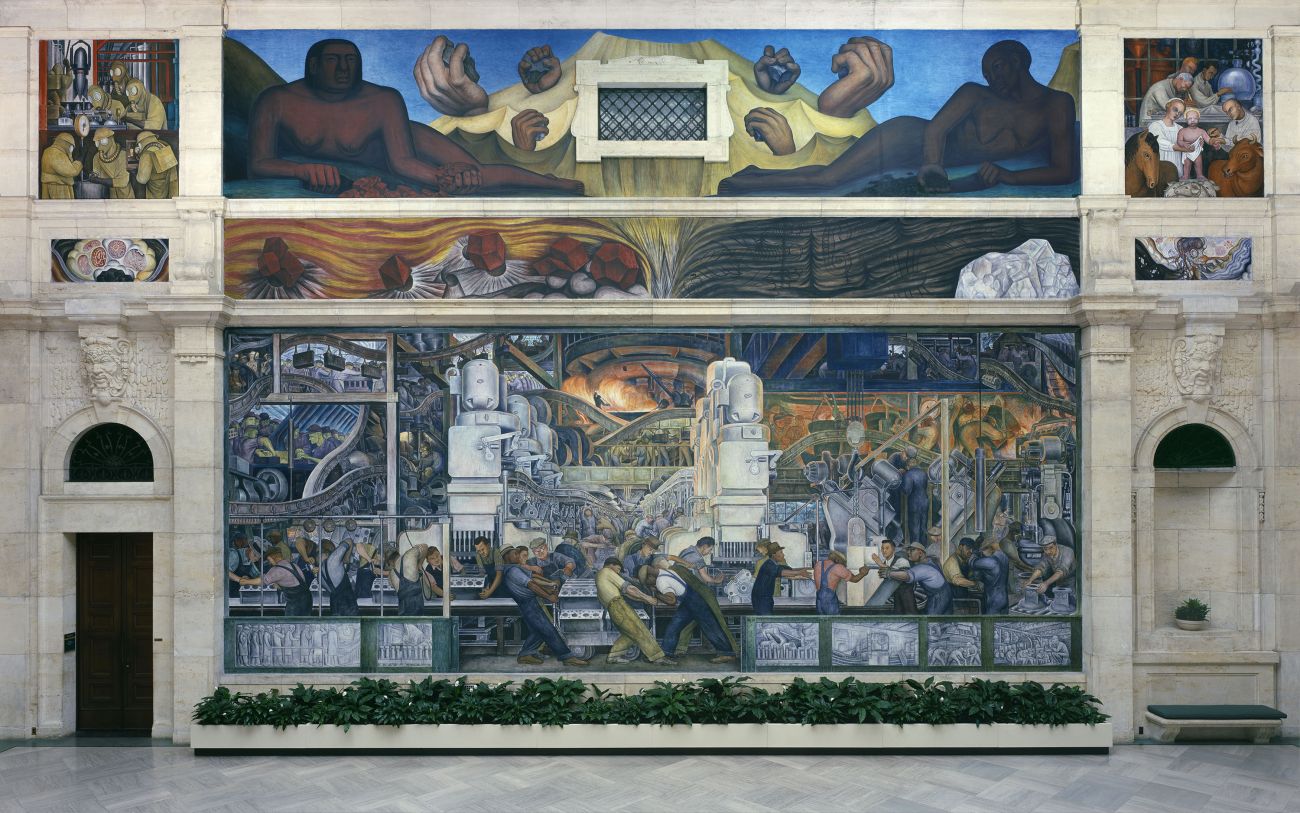

Rivera was invited to Detroit by Edsel Ford, heir to Ford Motor Co., to create a mural based on the development of industry in Michigan. Rivera’s creation would be the centerpiece of the Detroit Institute of Arts, DIA. Ford was the most powerful capitalist patron to have in Detroit.

Rivera’s commission was $10,000. Before the Great Depression, it would have taken the average U.S. worker like the Martinez brothers eight years to earn that amount.

The Martinez considered themselves blessed during the decade-long Depression because they kept their railroad jobs, though, their hours and wages were slashed.

Rivera always welcomed working-class visitors to the DIA to watch him work. The connection to the artists was deep among Mexican immigrants in the area. So, the Martinez brothers would hop on a trolley in Corktown and trek to unfamiliar territory: a big city art museum.

Kahlo sometimes offered them tamales and Coca-Colas. Rivera would show them the elaborate process of producing a fresco mural.

The couple sometimes preached politics. Rivera and Kahlo loved to use the word revolution, according to family lore.

The brothers fled Mexico years earlier to escape hellish revolution; their sister was raped by a soldier.

Rivera and Kahlo could praise socialist ideals and still have dinner at the Ford mansions – both Edsel’s in Grosse Pointe Shores and Henry’s in Dearborn.

For most working-class people, the slightest hint of being associated with communists usually meant losing your job. There was a real chance of being beaten by corporate goons, and, getting labeled a dangerous subversive by various government agencies. For the Martinez brothers, it could mean being illegally deported. Thousands of Mexican immigrants in Detroit were wrongly kicked out of the U.S. during the Depression.

At some point, Rivera offered a solution to some Mexican immigrants in Detroit: return to Mexico to form worker collectives.

Depression-wracked Detroit was the best opportunity the brothers ever had. Their children, including their daughters, could attend public schools with whites. They didn’t live in a boxcar, as they were forced to do in Texas years earlier. Their Corktown home had electricity and indoor plumbing.

That’s why my grandfather – the leader among his siblings – eventually explained to the artists the brothers would no longer visit the artists at the DIA.

“You are amazing, but you are troublemakers,” he told them, according to family lore.

Rivera and Kahlo erupted in laughter. They hugged and kissed the men goodbye.

I love the respect imbued in those conversations.

Those conversations give me hope in these current dire times because my family saw the value of Detroit even as many thought it was all gloom and doom here.

My mother and her five siblings were young children during this time. They cherished much of their experience for the rest of their lives. They talked of neighbors sharing meals, swapping goods and the many ways people pulled together to survive.

It instilled in them a lifelong bond to community and country. Three of my uncles went on to become decorated World War II soldiers and then lead successful middle-class lives. My mother and aunt would both earn college degrees. For decades, they fought for various civil rights issues for Detroit’s Latino community.

Detroit, then and now, has felt more severe pain than many communities. Like the best of Detroiters then and now, it makes us no-bullshit realists whose challenges burnish wisdom and strength.

And as Rivera’s and Kahlo’s art proves, a volatile Detroit can spark masterpieces.

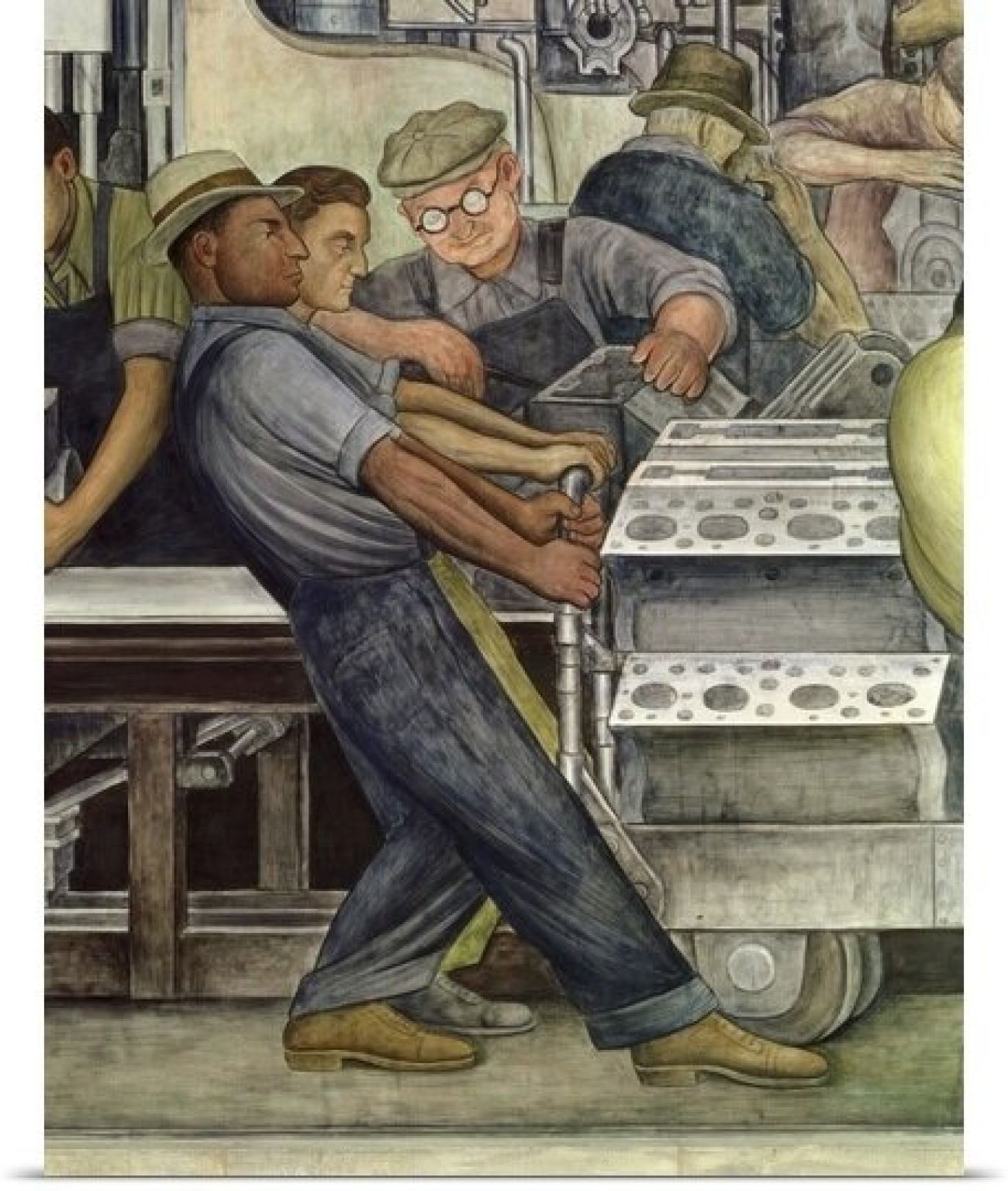

About Rivera’s Detroit Industry mural; historians have never determined the identity of one of the main workers depicted on the assembly line. (Most key figures are based on real people, or, sometimes a composite of people).

Whoever the unknown figure is, he’s beautiful. His skin is the color of cinnamon and he has high Indian cheekbones like that of many Mexicans with indigenous blood. He’s wearing blue overalls and a hipster white Fedora hat. He’s hauling a Ford engine block.

He strongly resembles my grandfather and his brothers.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!