How one businesswoman is drawing inspiration from a legendary madam

On January 11, 1987, somewhere in what is now Hutzel Women’s Hospital, a woman once known as Detroit’s top madam died from complications of a stroke. She was 75. Her name was Helen McGowan.

Nineteen minutes later, in the same hospital, Bailey Sisoy Isgro came squalling into the world. If you believe in the supernatural, you might imagine some spirit flitting around the halls, freed from one body, looking for another. In truth, this is more a story about how a young woman in Detroit became interested in one who’d preceded her in the city decades earlier, and is trying to channel her entrepreneurial spirit.

Isgro isn’t operating a house of prostitution, as McGowan had in Detroit through the mid-20th Century. She’s running a fledgling history tour business that turns Detroit’s rich past into fun outings, in a house that evidence suggests was once occupied by McGowan and, presumably, the string of women she managed, whose sexual services were for hire.

And she has the discarded antique condoms to prove it.

“An old (Detroit) police officer told me, ‘She ran a damn honest whorehouse,’” Isgro said, sitting in the parlor of the roomy fixer-upper on Farrand Park, off Woodward in Highland Park, which she bought in 2015 as a home base for her new business, Detroit History Tours. Working as a model maker for General Motors fills her days, but nights and weekends are spent making her house a suitable home for the Detroit History Club, the business’ parent organization.

Several times a month, Isgro opens the first floor for speakers, parties or other social events for the history-minded, who pay club membership and event fees. She lives on the second floor. The third, when it’s finished, will be a suite for a historian-in-residence to use as a home base.

It’s an ambitious plan, but the work has advanced steadily with the help of family and friends, who have taken the structure from a shag-carpeted wreck populated by squirrels and raccoons to a functional home modified for hospitality on a large scale. A commercial kitchen can turn out meals for a crowd. Several large tables can seat them. And folding chairs can be set up from the front room to the back sun porch to hear a reading or lecture.

“The ways of this world is strange. When a girl makes a mistake, they knocks her down for it. When a boy does it, all they say is boys will be boys. It ain't fair but that's what happens. You jus' got to get used to it.” -- Life advice delivered to the teenage girl who rose to become the Motor City Madam

“When (my partner and I) started this, we thought we might do four tours a year,” Isgro said. “Last year we did 117.”

The events and tours are designed for entertainment as much as edification. Wild Women of Detroit takes bus riders on a cruise around town to see the haunts of “broads, women, cats, ladies and Rosies.” Cops and Mobsters looks into Detroit’s rich history of organized crime. At the house, a Valentine-themed event presents a dessert tasting, along with looks at several speakers’ “historic crush,” and on some Saturdays there’s a brunch with “Interesting People Reading Interesting Things,” which Isgro calls “storytime for adults.”

“People are really interested in Detroit history,” Isgro said. “And they want to have a good time doing it.”

Helen McGowan, dead 30 years, serves as sort of an unofficial muse for the whole operation.

She did it her way

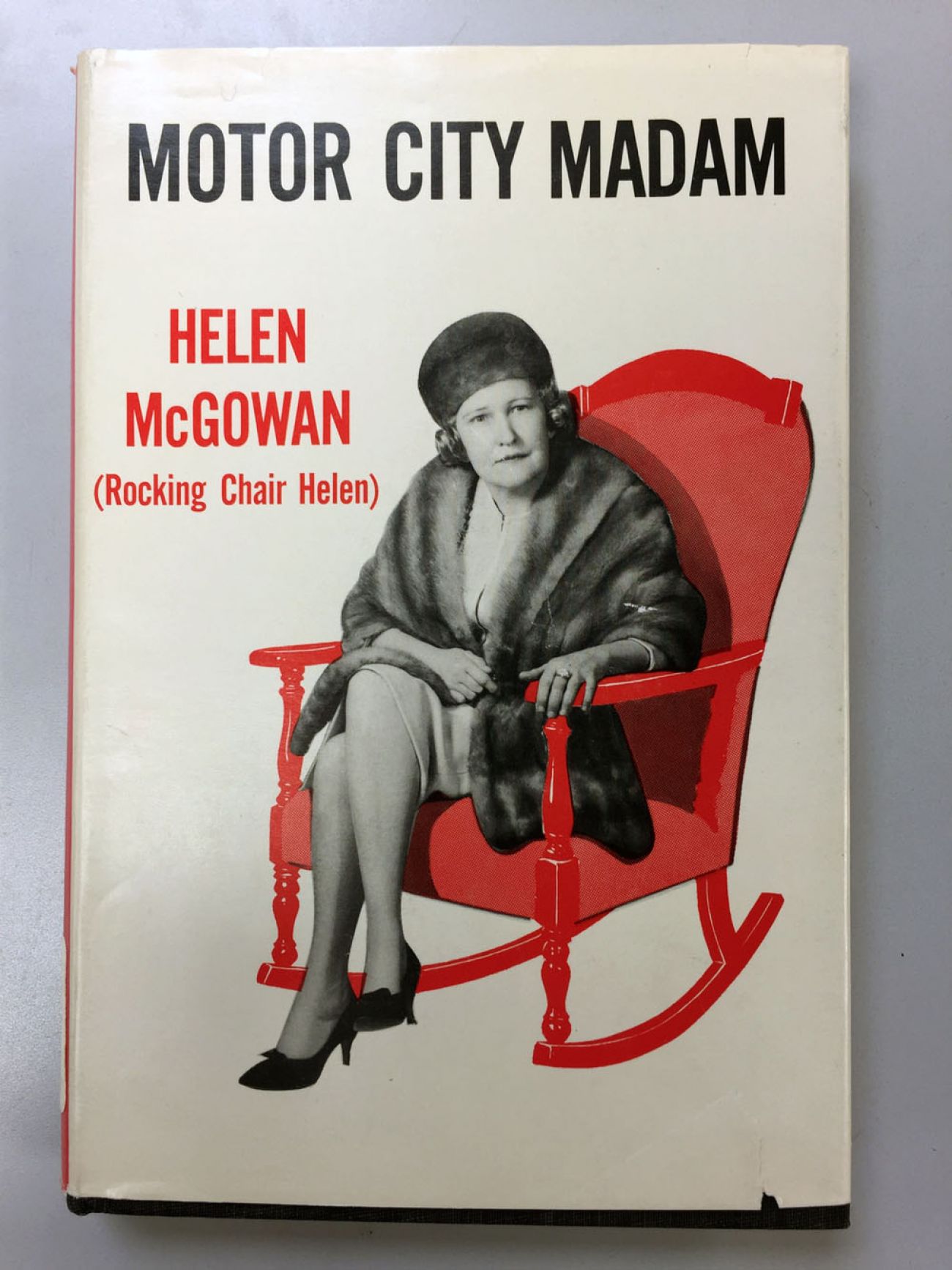

Most of what Isgro, or anybody, knows about Helen McGowan comes from a memoir she published in 1964. “Motor City Madam” had a printing of under 2,000 copies, and was later republished in paperback as “Big City Madam,” with a run of about 3,000, and despite breathless jacket copy on the original – “a shocking and important book...which should be read by ministers, police officials, and citizens concerned with the future of our community life” – it didn’t catch on. Occasional copies turn up on used-book websites, but it’s hard to find. A single copy lives at the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, but doesn’t circulate.

The woman revealed in its pages tells a life story both familiar and unexpected, credible and less-so. Born Mae Abisher in 1911, her early life was spent in hardscrabble poverty in Malden, Mo., a farm town in the state’s bootheel.

Poorly educated (but an avid reader), she’s cast out by her family after a dalliance with a farm boy leads to a pregnancy at 15, followed by a shotgun marriage that ends the same day as the wedding, when the bridegroom delivers a haymaker to her jaw and hops a freight out of town. She takes refuge with a woman who lives nearby, cares for her throughout her pregnancy and delivers a pronouncement that would become the theme of Helen’s life ever after:

“The ways of this world is strange. When a girl makes a mistake, they knocks her down for it. When a boy does it, all they say is boys will be boys. It ain't fair but that's what happens. You jus' got to get used to it.”

Once delivered of her child (who apparently was given away), Mae is shipped off to a sister in Flint, where she works for a while in the AC Spark Plug plant before moving first to Kansas City and then to Chicago. The roaring ‘20s and Prohibition are making Al Capone a household name. Mae and a friend go to work at his Cotton Club, on the recommendation of a man they knew only as John, last name Dillinger.

They leave after a few months, bound for Detroit, only slightly less action-packed than Chicago. And it’s in Detroit that Mae Abisher becomes Helen McGowan and finds her calling, first as a prostitute and later as a madam.

But what a madam.

“She did for prostitution what Ford did for factory work,” said Isgro. “She paid women better, kept them safe, made it a better experience for everybody.”

She was known as Rocking Chair Helen, which suggests a thrilling sexual trick but is, as McGowan explains in her memoir, just her favorite seat in the house, one she liked to be in when she knew the vice squad was coming through the door. “It calms my nerves,” she wrote.

As “Motor City Madam” tells it, she insisted her girls visit a doctor regularly, and paid for it. She charged less than the going rate, but made up for it in volume and loyal repeat customers. And while she was regularly raided and arrested, she kept it to a minimum by memorizing the faces of vice squad officers, spreading cash through “the racket boys,” i.e. organized crime, and being honest with all.

She also moved her house regularly.

Whose house is this?

Isgro said as many as 311 addresses in the Detroit area have been associated with McGowan’s business; in “Motor City Madam” she admits to having 30 different locations in a single year, always as a renter. When the house on Farrand Park was in escrow, a friend and fellow history buff told her, “you’re looking at a Helen house,” Isgro said. But renters generally aren’t in the public record, so they only had suspicions, drawn from the memories of aging neighbors, who recalled McGowan’s unique contributions to the war effort in the early 1940s as a nearby Ford plant was turning out combat tanks.

One day a friend was inspecting ceiling joists in the basement, running his hand along the top side of a beam. He touched a loose object, and pulled down a pewter mug filled with change, a silver-certificate bill, and a three-pack of condoms. On the side of the mug, an engraved name: Helen.

Isgro was thrilled. And as the work continued, more evidence turned up, objects abandoned in attics and odd corners. A book on birth control, a metal rod with a handle that might have been a sex toy (or a curling iron), and condoms. Lots of them.

In fact, there were so many condoms -- period-specific condoms in metal cases, rotted but still in their packaging, scattered throughout the rooms -- that they strongly suggest the house was more than just a residence.

One day someone unearthed a silver case in a pile of attic insulation. Isgro opened it and found a matchbook for Detroit’s Leland Hotel nestled inside; the case was a companion to the cigarette cases many men and women carried. She opened the matchbook and found no matches, but a condom.

Certainty isn’t always available to historians, Isgro said, who have to hedge their claims with lots of “evidence suggests” and “the record indicates,” but this trove of relics is good enough for her: This was once Helen McGowan’s house.

Ahead of her time

Prostitution isn’t always a pleasant business, and McGowan makes that clear in her memoir, telling stories of the girls she saw descend into heroin, alcohol or other degradations. But she reserves the sharp side of her tongue for the hypocrites, the prudes, the myriad societal judges who cannot reconcile the fact that people, especially men, will always seek sexual satisfaction, and not always within the institution of marriage. Having been one herself back in Missouri, she knew the cost, while her young husband escaped on the rails.

“Wrecked young lives is the price we are paying for the refusal to legalize and control prostitution,” she wrote. Detroit was a hard, masculine town when she was operating, with more men than women. What else were they supposed to do? To her, she was providing a vital public service.

She took a fierce pride in what she built, illegal and immoral by the standards of the time as it may have been:

“I am a working man’s madam,” she wrote. “Although lawyers, doctors and many other professional men frequent my parlors, the majority of callers are from the working class, the one-hundred-dollar-a-week boys. I charge a fair price, well within the means of the lonely employed worker. My men know they won’t be rolled; they don’t have to worry about venereal disease; they feel safe in my house. And they must certainly like my girls because some of my clients are twenty-five year veterans.”

Societal attitudes toward prostitution are changing, although they fall short of McGowan’s ideal of a legalized business. But more sex workers are speaking up for themselves, as feminists and entrepreneurs. Isgro believes McGowan would fit right in today. And she admires the dirt-poor girl who made something of herself the only way she could.

When Isgro bought the 5,000-square-foot money pit in Highland Park, she knew restoring it would take years, that the work would be hard, and that the business she was building would depend on it. But, she said, it’s all been worth it. Imagining Helen McGowan doing the same thing, under the same roof, helps.

“She came into my life at a time when I needed a role model, and in a weird way she kind of became it,” Isgro said. “Long after I’m gone, if someone meets someone I knew, I hope they’ll talk about me the same way.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!