Wayne County’s tired jail deputies work double shifts at low pay. Wanna apply?

DETROIT – It took a lot of dysfunction to bring Chuck Pappas to this lonely table, trying to cajole the jobless in one of the nation’s poorest cities to apply for a job they’ll probably quit in less than a year.

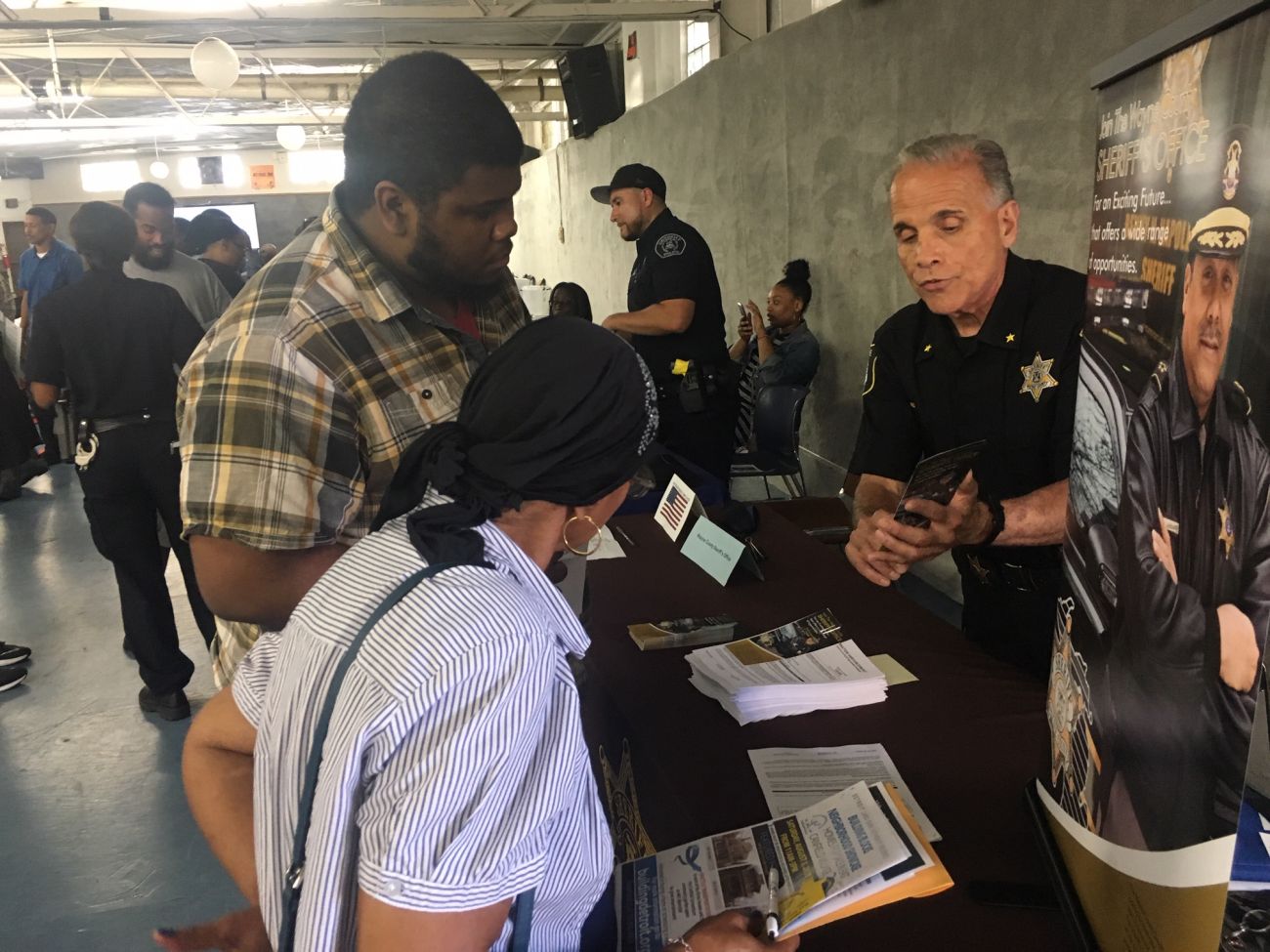

Pappas is a recruiter for the Wayne County Sheriff’s Office, which for a decade has had a chronic shortage of jail deputies. So he spends his days scouring job sites online and attending employment fairs such as one in August at the Alkebu-lan Village community center in Detroit’s east side, giving his pitch to folks like Marcus White, 19.

White listened politely, took a brochure and walked away with a confession.

“It’s not my first choice, to be honest,” he told Bridge Magazine.

It’s not many people’s first choice. Applications for law enforcement jobs are declining nationwide, but perhaps few places are as dire as Wayne County. For years, the county has been short 150 to 200 of its 925 budgeted jail deputy jobs, prompting overtime that balloons some deputies’ annual pay to well over $100,000 and, in one case, more than $200,000, said Undersheriff Dan Pfannes.

This year, the staff crunch is so bad administrators regularly impose mandatory overtime, forcing officers to work multiple double shifts and causing a spike in fatigue, alcoholism and disability, union officials say.

“You have broken the system. You have broken our members. They are so tired, so fatigued, they are refusing to work anymore,” said Reginald Crawford, president of the Wayne County Deputy Sheriff’s Association.

“How would you feel if you had to work double shifts, five days in a row? Our members are overworked, stressed out and under duress. This is a dangerous situation.”

Part of the trouble stems from attrition, distrust of police and pay – $35,000 to start compared to the $44,000 median salary for corrections officers nationwide. Critics contend the county’s deputy shortage could be abated if there weren’t so many inmates unnecessarily filling its three jails.

The county annually spends about $15 million in overtime atop $103 million for jail operations, guarding inmates who more often than not remain behind bars because they are too poor to make bail.

The ACLU of Michigan, which is suing the county as well as the city’s 36th District Court over what it calls a “broken cash bail” system, found that 62 percent of the jails’ average daily population of 1,600 inmates are pre-trial detainees unable to make bond.

“The money bail system has morphed into mass incarceration for the poor,” Dan Korobkin, deputy legal director of the ACLU of Michigan, said when the suit was filed in April.

This spring, the Wayne County Commission approved a resolution calling for reforms and supporting bipartisan legislation in Lansing that would require judges across the state to release people before trial unless there is a “preponderance of evidence” that they’re violent or pose a flight risk.

“This is a huge financial cost to everyone,” said Alisha Bell, chairwoman of the Wayne County Commission, who sponsored the resolution, told Bridge.

“It puts a huge strain on our deputies, and taxpayers as well. This is (overtime money) we could be using for services in our communities.”

The county is participating in a task force working to reduce jail populations statewide with safe and less costly alternatives, a movement that’s drawn bipartisan support in Michigan and across much of the nation. The group, which formed as a result of an April executive order from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, is examining why jail populations statewide have tripled in 50 years even as crime has plunged.

Crime is down in Wayne County as well, although Detroit remains one of the nation’s most violent big cities.

The task force is expected to present findings about Wayne County jails during an Oct. 18 public hearing at Wayne State University, said Terry Schuster of the Pew Charitable Trust’s Public Safety Performance Project, which is assisting the task force.

Sheriff Benny Napoleon said he believes “America has too strong an appetite for incarceration,” but he said “there’s nothing I can do about” the number of inmates in his jails.

“I don’t let anyone in and I don’t let anyone out,” Napoleon told Bridge. “We follow the sentences given by judges.”

Timothy Kenny, chief judge of Wayne County Circuit Court, said county officials are meeting Tuesday with an outside group, the Vera Institute of Justice, which analyzed the county’s jail population to determine “who is in jail, for what and what are the best practices that could be employed to reduce that population.”

Pfannes, the undersheriff, said the county has trimmed its average daily population to 1,600, down from 2,800 in 2007, a 43 percent drop. That’s partly due to an aggressive tether program. Ten years ago, about 50 inmates were monitored by electronic tether on any given day, compared to about 700 today who are released on tethers as an alternative to bond or as part of their sentences.

That’s a $30 million savings: Daily costs are $35 to monitor tethers compared to $140 per day for those in jail, Pfannes said.

“Despite what people think, law enforcement understands there are other ways out of this problem other than to incarcerate people,” Pfannes said.

“We are already picking off the low-hanging fruit.”

‘This is a crisis’

Pfannes said Wayne County is a model for seeking alternatives to incarceration, and its officials are working with legislators and others on models to reduce jail populations.

Both Pfannes and Napoleon said they agree the jail staffing crisis is bad for both deputies and inmates.

“There’s no doubt in my mind this is a non-sustainable model that is taking a toll on all involved,” he said.

The deputy shortage routinely forces some jail officers to work 60 hours or more a week and contributes to a quarter of jail workers take time off under the Family Medical Leave Act due to stress.

This year, the department instituted mandatory overtime, prompting so much discipline against deputies for declining to work extra hours that union leaders – who also work in the jail – are now devoted full time to defending members at disciplinary hearings, said Crawford, the union president.

Staff-inmate ratios are mandated by a 2005 consent decree against the county caused by overcrowded jail conditions. For safety reasons, Pfannes said he couldn’t disclose the ratios or how many deputies are assigned at a time to jails.

When those staffing levels aren’t met and not enough officers volunteer for overtime, jail administrators declare staffing emergencies that make overtime mandatory, Crawford said.

Last year, there were no staffing emergencies. This year, there have been 20 since Memorial Day, Crawford said.

The difference: Deputies could earn double time last year if they volunteered to work both of their two days off in one week. (The double pay would only begin to accrue on their second extra day.)

This year, they can only get time and a half, Crawford said.

One weekend this summer, 50 jail deputies of the 350 who were supposed to work called in sick, Crawford said.

Another officer, who worked 102 hours in one week, was suspended for six days for refusing another shift because he had to care for his father after double bypass surgery, said Allen Cox, a union vice president.

“This is a crisis. We have deputies almost driving off the road on their way home, drinking more, getting divorced, being estranged from their families. All because of overtime,” Cox said.

An emergency meeting between the union and administrators is scheduled for Tuesday, Sept. 24. Napoleon, the sheriff, said he’s sympathetic to deputy complaints.

“I don’t disagree with them,” he said. “No one minds working occasional overtime, but the way it is, it’s keeping them from their families. I understand their stress.

“But I have a jail to run.”

‘This job is not very attractive’

Union and sheriff’s officials agree the staffing shortage makes it more difficult to recruit for a job that’s already a tough sell.

“The job is not very attractive,” Crawford said. “You are working in dangerous conditions for low pay, and then adding three to four overtime shifts to a 40-hour week? The ones who come leave within months.”

Police agencies and jails nationwide also face shortages, as officers retire and agencies that laid off workers or stopped hiring during the Great Recession struggle to compete for recruits in a hot economy. Nationwide, the number of sworn officers fell by 23,000 to 701,000 from 2013 to 2016, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Since last year, about 90 of the Wayne County deputy union’s 720 members retired or quit. Last week, a class of 30 recruits graduated from training and will soon begin working in jails. Many won’t stick long.

“Guaranteed, after 30 days, that number will be cut in half,” said Robin Hornbuckle, a union vice president.

Pappas, the jobs recruiter, refers to a “revolving door” of new workers, with most leaving for better-paying, less-stressful jobs after six months or a year.

At the east side community center, his pitch to prospective workers includes promises that beginning deputies can make $61,000 per year because of overtime.

But more than 90 percent of applicants don’t make it through the process. Many find more attractive offers or are waylaid by restrictions on people with criminal records working in jail settings, said Pfannes.

“Are you felon-friendly?” one job seeker asked Pappas at the August job fair.

“The whole state of Michigan isn’t felon friendly,” he responded, referring to laws that ban those convicted of felonies from working in jails.

Pappas told Bridge his job is made harder because “nobody wants to be a cop anymore.” That’s partly because of a societal backlash against examples of improper use of force, he said, but also because benefits and pay have gotten worse.

Even if deputies start with the county, they often leave soon for other departments, Pappas said.

“It’s a screwed-up system,” he said.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!