Academic State Champs: How to make sense of your school’s M-STEP scores

We know that Michigan students struggled on the more rigorous M-STEP test, given for the first time last spring and tied to the implementation of the Common Core State Standards.

What hasn’t been shared, until now, is how well elementary and middle schools across Michigan performed on the standardized test compared with peer schools in the state.

That’s why Bridge Magazine has crafted an M-STEP database, using many of the tools of the Academic State Champ analysis for which Bridge is known. In short, you can now see how schools in your community fared on the M-STEP in different grades and subject areas compared with Michigan schools of similar income levels, considered a key predictor of academic success.

Statewide, the best performance on the M-STEP was among 3rd graders in English Language Arts, where 50 percent were deemed proficient. All other statewide scores were lower; only 12 percent of fourth graders were proficient in science.

For some, the lower results – released to parents just last month – are proof that teachers need more support as they transition to the different standards and methods of Common Core. To opponents, they’re evidence that replacing the state’s 44-year-old MEAP (Michigan Educational Assessment Program) test last year was unnecessary and even potentially harmful to students.

Statewide, the results show that serious problems exist in certain grades and subject areas. At 226 schools, not a single fourth-grader was proficient in science; in fifth grade, 150 schools had no one proficient in social studies.

But the scores are not uniformly bad; and many schools’ students succeeded. At Handley School in Saginaw, 93 percent of its 233 third, fourth and fifth grades were proficient in English, and 79 percent were proficient in math, far outstripping both state averages and peers at 155 similar schools.

The Bridge difference

Bridge’s M-STEP database shows how individual elementary and middle schools performed on the test, and then compares that performance with schools across Michigan with a similar socioeconomic profile. Poverty levels are considered a critical (though not sole) factor in academic success.

Bridge measures poverty levels by the percentage of students eligible for a free or reduced-priced lunch under federal guidelines.

For example, in the more affluent Grosse Pointe schools in Wayne County outside Detroit, 84 percent of fourth graders at Ferry Elementary were proficient in English, well above the state average (47 percent) and above the 71 percent at 100 schools across the state that have relatively few impoverished students.

In the same district, 58 percent of students are eligible for a free or reduced-price lunch at Poupard Elementary – a rate seven times higher than Ferry. At Poupard, 47 percent of fourth graders were proficient in English. Compared to Ferry, that’s substantially lower. But it matched the statewide percentage who were proficient in English and, when compared with 200 similar schools (where between 53 and 63 percent of students were eligible for free and reduced lunch), Poupard students did better. In its third, fourth and fifth grades, Popuard students exceeded their peers on five of the eight tests, the Bridge analysis shows.

More rigorous standards

The Common Core standards represent a massive shift in teaching and assessment. Students are challenged to think and solve problems differently than they were in years past.

On the online M-STEP, there were more than multiple-choice questions. The goal, advocates say, is to improve critical thinking, raise student achievement and better prepare students for a challenging global environment.

It has been a controversial change as some parents have complained that the new methods have made it difficult to help their children with homework. Common Core, which was adopted by a majority of states, relies less on memorization and more on learning different ways to solve problems.

Amber Arellano, executive director of Education Trust Midwest, which advocates for higher academic achievement in Michigan and supports Common Core, said the first year of M-STEP results point to a need to pour more resources into training to help teachers make the transition to Common Core.

“I do think the state needs to get serious in supporting college and career standards,” she said.

She and others point out that lower scores were expected in the first year, and that other states that have made the switch – designed in part to allow for better comparisons among states – also experienced declines.

But the scores should not prompt anyone, she said, to discount the worth of the overhaul itself. “This is an opportunity,” she said. “We should not fear the data.”

Melanie Kurdys, an opponent of Common Core, agrees, in part, with Arellano. She thinks teachers do need more support. But Kurdys said Michigan’s lower test scores were not the byproduct of bad standards that prompted a swith to the Common Core standards, but poor teacher training.

Kurdys, of Portage, leads a group pushing back. By dropping the MEAP and its decades-long history of test results, Michigan lost the ability to track statewide progress by switching to the new test. She said she fears it’ll be years before the state will know whether Common Core works – and if it didn’t, the change will have been a waste of time and money.

“I still believe we’re experimenting on our children,” she said.

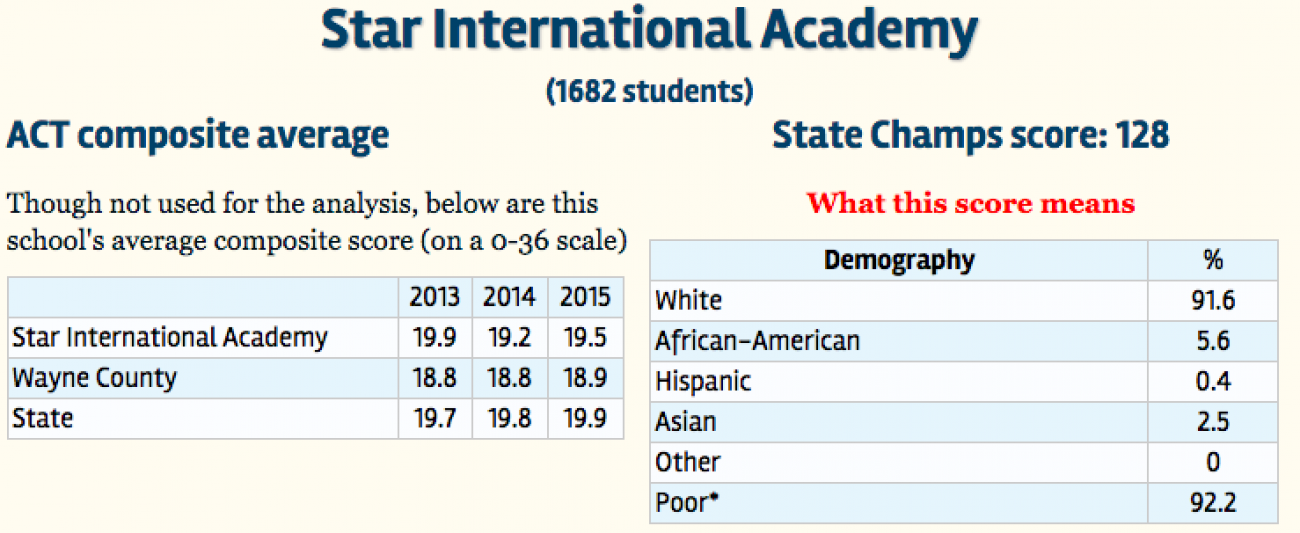

On Tuesday, Bridge released its fifth annual Academic State Champs, recognizing only overachieving high schools this year based on how they performed on the ACT, when accounting for poverty.

Bridge is not recognizing State Champs at the elementary or middle-school level this year; that’s due mostly to the state’s switch from MEAP to the M-STEP last year. Bridge concluded that one year of testing is not sufficient to accurately evaluate a school’s performance; the ASC formula usually relied on three years of testing.

The M-STEP, initially planned as a stop-gap assessment as the state developed a new test, will be around through 2018.

“Last spring’s M-STEP results, set the new baseline from which to measure, support and improve student learning," Janet Ellis-Jarzembowski, a spokesperson for the Michigan Department of Education, said in a statement to Bridge. "As student knowledge increases, student achievement on state assessments overtime should increase and will help ensure all students are prepared for success in college and the workplace.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!