Long-term fixes to Michigan school funding unlikely this year

At DeWitt Junior High, it’s not uncommon to see kids wearing trendy North Face jackets and the coolest gym shoes as they tromp around campus, nestled in this bedroom community just north of Lansing’s vaulted halls of power. They come from middle-income families for the most part.

So when the school district last fall promoted BYOD – bring your own device – eighth-grader Rheanna Wey arrived with an iPad, which she’d paid for with babysitting money two years ago. The iPad isn't new, but it’s faster than the district’s desktops, half of which are seven years old.

Indeed, most DeWitt families can afford speedy, useful technology – the tablets, laptops and smart phones that have become essential in educational settings. Good thing, because the school district cannot, even though the median income in DeWitt is $75,848.

“Parents will ask why we don’t have the technology when we live in a middle-class community. They don’t understand how we can be one of the lowest-funded districts in the state,” said John Deiter, superintendent of DeWitt Public Schools.

DeWitt gets the minimum amount of school aid from the state ($7,026 per pupil) and receives little federal money for low-income students. While Michigan communities can pass millages for local school construction and technology, DeWitt lacks enough people or businesses to ante up big bucks. And the district’s tight budget leaves little for academic extras, such as more support for students struggling with math.

In Deiter’s view, Michigan’s 20-year-old school funding law, known as Proposal A, is neither equitable nor fair to DeWitt’s children. DeWitt ranked 775 of 812 districts and charter schools in Michigan in total funding per pupil last school year, Michigan Department of Education data show.

Many other small to middling, and middle-income, districts face a similar dilemma: too affluent to receive much funding for low-income students, not wealthy enough to be exempt from the local funding limitations of Proposal A.

Deiter said at the very least he’d like to see Lansing create a state school construction fund, like other some states have, that would give communities more money to build and equip facilities.

“Our retirement costs are up by a million since 2007,” he said. “Add inflation, we’re getting the same per pupil. I would challenge anyone to come in and find fault with how we’re spending money in DeWitt. I believe we’re very fiscally responsible. I wouldn’t say we’re in a crisis. We’re at a plateau. Without some relief, I don’t know how we’re going to balance the budget. I don’t know what else we can cut.”

School funding fix elusive

State legislators on both sides of the aisle expect education funding to be a major discussion in this fall’s election season. Partisans may quarrel about how to fairly fund schools, but on two issues they do agree:

A short-term budget deal amounts to “kicking the can down the road” on reforming the school funding formula in Michigan.

A longer-term funding solution is needed, but remains politically difficult in an election year.

So as candidates for governor debate whether more or less money has gone toward education during Gov. Rick Snyder’s first term, and as Michigan continues to earn mediocre grades on national studies of education spending and performance, we’re likely to see more can kicking this fall.

Not only are long-term solutions unlikely, there is not even legislative support to fund a study of how much should be spend for Michigan students to compete with those in higher-performing states.

Snyder’s proposed budget for the upcoming school year recommends $11.7 billion for K-12 schools, an increase of $322 million over the current year (along with cuts to some specific programs). Most of the new money will help districts pay down pension debts, with the remainder adding anywhere from $83 to $111 to the per-student payments school districts receive from the state.

Two competing proposals ask the legislature to give more money to local districts to spend as they see fit – they differ mostly in degree. The proposals look alike, but are rooted in very different ideology.

Option one: Cut some, help all

Many education groups across the state banned together in February to announce an alternative to Snyder’s education budget – one they call “Classrooms and Kids.” Their idea calls for cutting more than $200 million in so-called categorical funding that is earmarked for special initiatives, such as to help online schools and other programs. Some cuts the group proposes: $80 million that goes to schools that meet “best practices” standards; $10 million for at-risk students; $2 million for robotics and $22 million for retirement costs. Under “Classrooms and kids,” that money would be spread instead among all public schools.

Under this approach, schools across Michigan would get $250 to $291 more per pupil when added to the governor’s proposed increases, the group says.

It is unclear whether allowing this money to be spread more evenly among all schools would leave less money for schools that are heavily dependent on this special funding.

“Classrooms and Kids” is supported by the Tri-County Alliance for Public Education, a group of about 85 school districts in Southeast Michigan; 12 intermediate districts; the Michigan Association of School Administrators as well as the Michigan Association of School Boards and Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals.

“This is a step in the right direction. It wouldn’t surprise me if others say it’s not enough,” said Robert Livernois, superintendent of Warren Consolidated Schools and president of the Tri-County Alliance. “We are working hard everyday to make sure we’re funding our classrooms properly and that’s the greatest challenge.”

Option two: Cut almost all categoricals

Meanwhile, charter school advocates want the solution to school funding to include the state eliminating a greater amount of categorical spending.

The Great Lakes Education Project is lobbying for categorical funds to be cut by $1.4 billion – more than five times what education groups are suggesting – so that about 90% of all state investment in K-12 would be spread equally among the schools. Under the GLEP plan, schools across Michigan would get a minimum of more than $8,200 per student (not including the 50-plus highest funded, “hold harmless” districts). That amounts to increases ranging from $201 to $1,224 per-pupil.

GLEP’s proposal would almost certainly benefit charter schools. Although charter schools do not participate in the pension fund, this proposal would allow charters to pocket a share of state funds previously earmarked to pay pension debts.

GLEP, a charter and school of choice advocacy group, has said it plans to donate between $500,000 and $1 million to political candidates that support its agenda.

A long-term fix to school funding will require tough legislative talks in Lansing, said Dan Quisenberry, president of the Michigan Association of Public School Academies, a charter school group that supports deep cuts to categoricals and equal per-pupil funding across the state.

“What’s happening right now isn’t the solution. There’s no explanation except for history as to why there are differences between per pupil funding,” he said. A serious discussion must involve brave lawmakers willing to dissect how schools in their districts manage their money, Quisenberry added.

“If this is about getting more or less money and no talk about how it’s spent, the conversation will go the way these conversations have gone in the past – nowhere.”

DeWitt’s dilemma

In 2009, after several failed bond proposals, DeWitt voters approved a millage to support $10.4 million in school building improvements, including wireless access to the Internet. But the funds did not pay for electronic devices for DeWitt students.

The junior high school has mobile carts stocked with Netbook and Chromebook laptops that classes can share, along with about 90 desktops. But no smart boards, few projectors and no district-wide automated parent notification system for snow days like those used in other districts.

In February, Deiter, the superintendent, sat in a legislative conference room in Lansing and explained DeWitt’s issues to a senate appropriations subcommittee on school aid.

“I would challenge anyone to come in and find fault with how we’re spending money in DeWitt. Without some relief, I don’t know how we’re going to balance the budget. I don’t know what else we can cut.” – Supt. John Deiter, DeWitt Public Schools

With senators at one end of a massive table and the superintendent at the other, Deiter described how budget cuts were nudging up class sizes in his 3,000-student school system. DeWitt now shares a food services director with East Lansing schools, and a high school counselor and some reading specialists had to be cut to help balance the budget.

East Lansing – a district only 15 minutes away – gets a foundation grant of $8,049 per pupil from the state, while DeWitt receives $7,026 per pupil due to the way the Proposal A school funding law works.

Deiter said he was testifying because he knew that major funding decisions for Michigan students take place in Lansing. He was testifying because educators are being told to increase standardized test scores without increasing costs.

Meanwhile, Michigan ranks among the bottom tier of states in the nation on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, tests.

“A lot of studies say there’s no direct correlation between test scores and money,” Deiter said, but “when you’re constantly trying to do more with less, something’s got to give.”

He welcomes the small, one-year infusion of cash the governor is pushing for the fall. But he is doubtful a permanent fix is in the offing for the sake of 47 Michigan school districts in deficit and the remainder that have seen state per-pupil spending decrease by 6% since 2010-11. The political winds are not blowing in that direction.

DeWitt for years performed well on the state’s MEAP test, but last fall only 38% of DeWitt third-graders scored proficient on the MEAP math. “I’d like to do math intervention but I don’t have the money to hire staff,” Deiter said. “If this is the best Michigan can do, we’re well behind. We’ve got a lot of work to do.”

The true cost of education

Of the 200 Michigan school districts that are part of a group called the School Equity Caucus, some agree with proposals to redistribute the categorical funds earmarked for special programs, other districts do not.

“There is nothing that’s not politicized,” said Gerald Peregord, executive director of the caucus.

“We do things backwards in Michigan. We figure out how much money we’re going to spend and then say, ‘Educate the kids,’” said Peregord, who thinks Michigan should conduct an adequacy study to first determine how much it would cost to give students across the state an opportunity to receive a quality education. “I try to be an optimistic person, hoping that sooner or later our leaders will recognize we’re not talking about dollars, we’re talking about kids.”

For now, there is no political urgency to fix Proposal A.

“We’ve been talking about this for five, six years since 2007-08 when the economy went bad and showed Proposal A was not working the way it was supposed to,” Peregord said. “There’s talk, but no traction on Proposal A because it’s a big project.

School officials cope with tighter funding by skillfully cutting their way to balanced budgets. However, the number of financially distressed school districts is growing in Michigan, making it increasingly important for the state to find a more permanent solution.

“A majority (of schools in the Equity Caucus) are already looking over into the abyss or can see the cliff. They’re not in deficit yet, but if trends continue they will be,” Peregord said. “(Proposal A) is not working and soon it’s going to be proved to not work. But it’s going to be too late for some kids.”

No pressure to change

Former Senate Majority Leader Dan DeGrow has a unique vantage point. He was one of the architects of the Proposal A school funding law in the 1990s and is now superintendent of St. Clair County’s intermediate school district.

It took 20 years, a dozen failed proposals and a school district going broke in Kalkaska (shutting its doors three months before the end of the school year) for lawmakers to change the school funding process in 1994. The legislature canceled all state school funding, forcing lawmakers and voters to create and approve Proposal A in 1994 to restructure education aid.

Proposal A did its job – cutting and capping property taxes while significantly narrowing the funding gap between low and higher-funded school districts.

Since 1994 when Prop A was approved, the gap between bottom and high funded districts has improved – from $2,300 per pupil then, to about $1,000 per pupil today.

While Prop A reduced the gap between poor and wealthier districts, it was never intended to deliver additional funds to districts that need more resources to educate their students. DeGrow also noted with 2-cents from the state sales tax going to schools, when the economy slows, less money is generated for schools.

“Proposal A works fine when the state has money. When the state doesn’t have money, schools have to tighten,” DeGrow said.

In DeGrow’s view, an overhaul of school funding also requires something that is lacking now, but was present in 1994: a groundswell of angry voters demanding change.

“Superintendents have done a good job holding the ship together,” DeGrow said. “Do parents notice things are worse? I don’t know. Outside urban areas the answer is probably, no.”

People move politicians. Politicians move money.

“I think to change things, the public has to be outraged,” DeGrow said. “I don’t see the public outraged yet.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

8th grader Emma Clark, 14, ponders a problem during a science class at the DeWitt Junior High School. Students at DeWitt commonly use technology in classroom, sometimes working on their personal devices. (Bridge photo by Marcin Szczepanski)

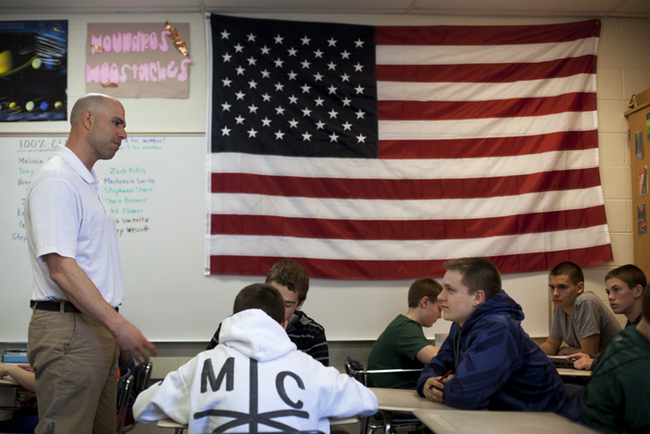

8th grader Emma Clark, 14, ponders a problem during a science class at the DeWitt Junior High School. Students at DeWitt commonly use technology in classroom, sometimes working on their personal devices. (Bridge photo by Marcin Szczepanski) Teacher Kirk Moundros explains algebra to his 8th graders who often use personal tablets and smart phones to work on projects during his class at DeWitt Junior High School. (Bridge photo by Marcin Szczepanski)

Teacher Kirk Moundros explains algebra to his 8th graders who often use personal tablets and smart phones to work on projects during his class at DeWitt Junior High School. (Bridge photo by Marcin Szczepanski) DeWitt Junior High 8th graders use a personal smartphone to work on a project in an algebra class. (Bridge photo by Marcin Szczepanski)

DeWitt Junior High 8th graders use a personal smartphone to work on a project in an algebra class. (Bridge photo by Marcin Szczepanski)